US town’s frugal man dies with big secret: US$3.8 million that he gave to 4,200 residents

[ad_1]

His will had brief instructions: US$3.8 million to the town of Hinsdale to benefit the community in the areas of education, health, recreation and culture.

“I don’t think anyone had any idea that he was that successful,” said Steve Diorio, chairperson of the town select board who would occasionally wave at Holt from his car. “I know he didn’t have a whole lot of family, but nonetheless, to leave it to the town where he lived in … It’s a tremendous gift.”

The money could go far in this Connecticut River town sandwiched between Vermont and Massachusetts, with abundant hiking and fishing opportunities and small businesses. It was named for Ebenezer Hinsdale, an officer in the French and Indian Wars who built a fort and a grist mill. In addition to Hinsdale’s house, built in 1759, the town has the nation’s oldest continually operating post office, dating back to 1816.

There has been no formal gathering to discuss ideas for the money since local officials were notified in September. Some residents have proposed upgrading the town hall clock, restoring buildings, maybe buying a new ballot counting machine in honour of Holt, who always made sure he voted. Another possibility is setting up an online drivers’ education course.

Organisations would be able to apply for grants via a trust through the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, drawing from the interest, roughly about US$150,000 annually.

Hinsdale will “utilise the money left very frugally as Mr Holt did”, town administrator Kathryn Lynch said.

Holt’s best friend Smith, a former state legislator who became the executor of Holt’s estate, had learned about his fortune in recent years.

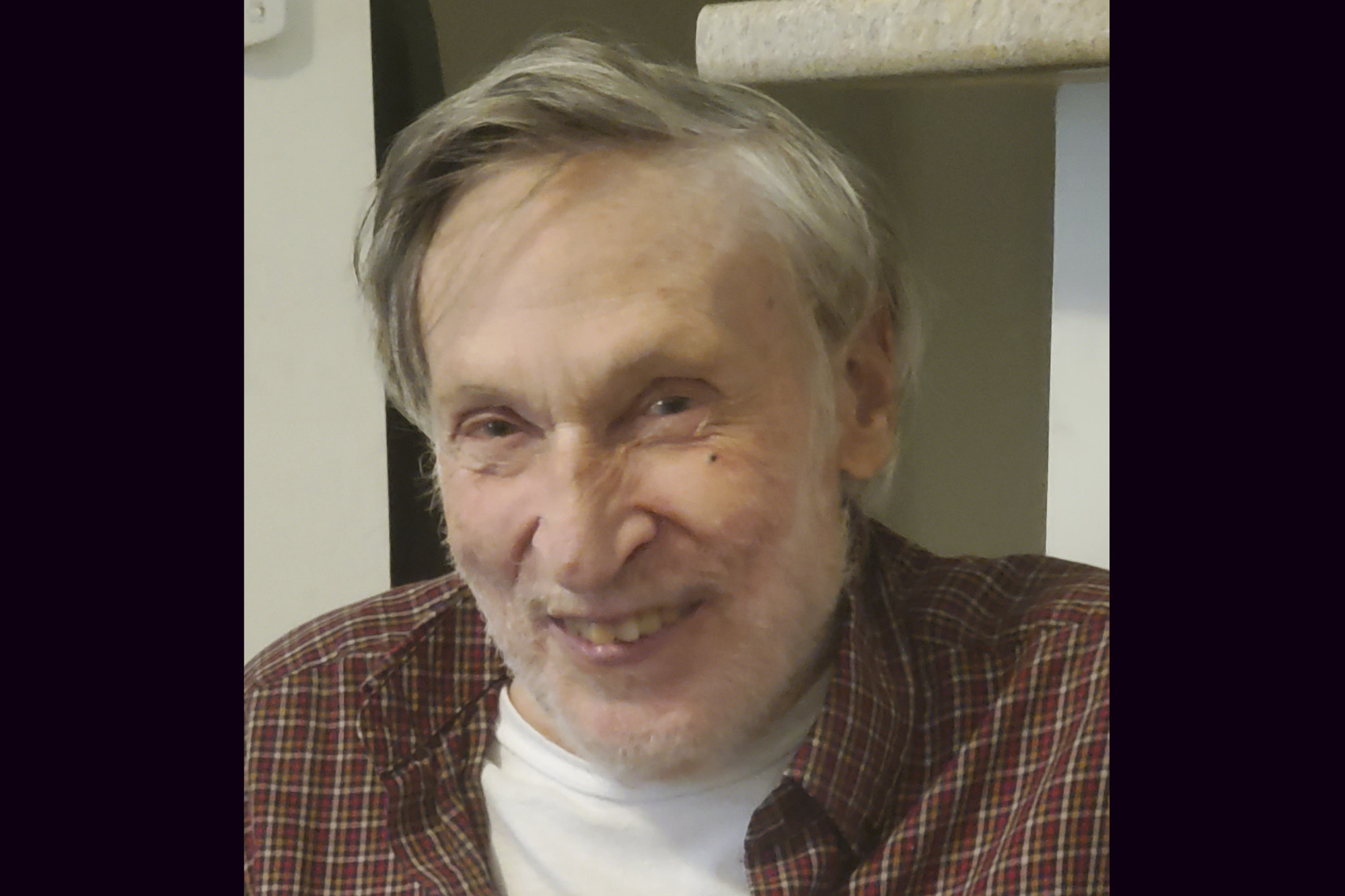

He knew Holt, who died in June at age 82, had varied interests, like collecting hundreds of model cars and train sets that filled his rooms, covered the couch and extended into a shed. He also collected books about history, with Henry Ford and World War II among his favourite topics. Holt had an extensive record collection too, including Handel and Mozart.

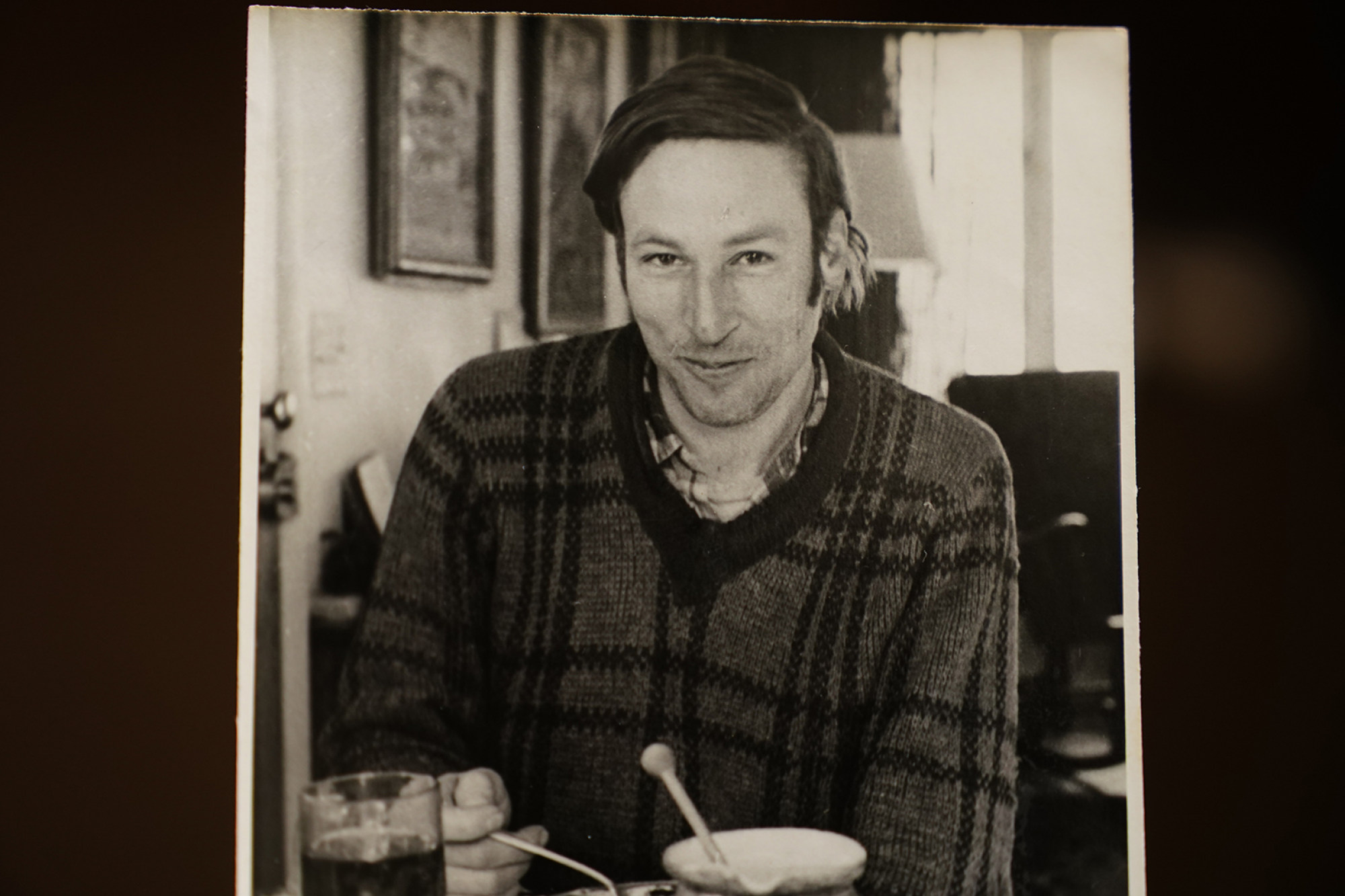

Smith also knew that Holt, who earlier in life had worked as a production manager at a grain mill that closed in nearby Brattleboro, Vermont, invested his money. Holt would find a quiet place to sit near a brook and study financial publications.

Holt confided to Smith that his investments were doing better than he had ever expected and was unsure what to do with the money. Smith suggested that he remember the town.

“I was sort of dumbfounded when I found out that all of it went to the town,” he said.

One of Holt’s first investments into a mutual fund was in communications, Smith said. That was before mobile phones.

Holt’s sister, Alison, 81, said she knew her brother invested and remembered that not wasting money and investing were important to their father.

“Geoffrey had a learning disability. He had dyslexia,” she said. “He was very smart in certain ways. When it came to writing or spelling, he was a lost cause. And my father was a professor. So, I think that Geoff felt like he was disappointing my dad. But maybe socking away all that money was a way to compete.”

She and her brother grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts. Their father, Lee, taught English and world literature at American International College. Their mother, Margaret, had a Shakespearean scholar for a dad. She was an artist who “absorbed the values of the Quaker Society of Friends”, according to her obituary. Both parents were peace activists who eventually moved to Amherst and took part in a weekly town vigil that addressed local to global peace and justice issues.

Their children were well-educated. Geoffrey went to boarding schools and attended the former Marlboro College in Vermont, where students had self-designed degree plans. He graduated in 1963 and served in the US Navy before earning a master’s degree from the college where his father taught in 1968. In addition to driver’s ed, he briefly taught social studies at Thayer High School in Winchester, New Hampshire, before getting his job at the mill.

Alison remembers their father reading Russian novels to them at bedtime. Geoffrey could remember all those long names of multiple characters.

He seemed to borrow a page from his own upbringing, which was strict and frugal, according to his sister, a retired librarian. His parents had a vegetable garden, kept the thermostat low, and accepted donated clothes for their children from a friend.

She said Geoffrey did not need a lot to be happy, did not want to draw attention to himself, and might have been afraid of moving. He once declined a promotion at the mill that would have required him to relocate.

“He always told me that his main goal in life was to make sure that nobody noticed anything,” she said, adding that he would say “or you might get into trouble”.

They did not talk much about money, though he would ask her often if she needed anything. “I just feel so sad that he didn’t indulge himself just a little bit,” she said.

But he never seemed to complain. He also was not always on his own, either. As a young man, he was briefly married and divorced. Years later, he grew close to a woman at the mobile home park and moved in with her. She died in 2017.

Neither Alison nor Geoffrey had any children.

Holt suffered a stroke a couple of years ago, and worked with therapist Jim Ferry, who described him as thoughtful, intellectual and genteel, but not comfortable following the academic route that family members took.

Holt had developed mobility issues following his stroke, and missed riding his mower.

“I think for Geoff, lawn mowing was relaxation, it was a way for him to kind of connect with the outdoors,” Ferry said. “I think he saw it as service to people that he cared about, which were the people in the trailer park that I think he really liked because they were not fancy people.”

Residents are hoping Hinsdale will get noticed a bit more because of the gift.

“It’s actually a forgotten corner in New Hampshire,” said Ann Diorio, who’s married to Steve Diorio and is on the local planning board. “So maybe this will put it on the map a little bit.”

[ad_2]

Source link