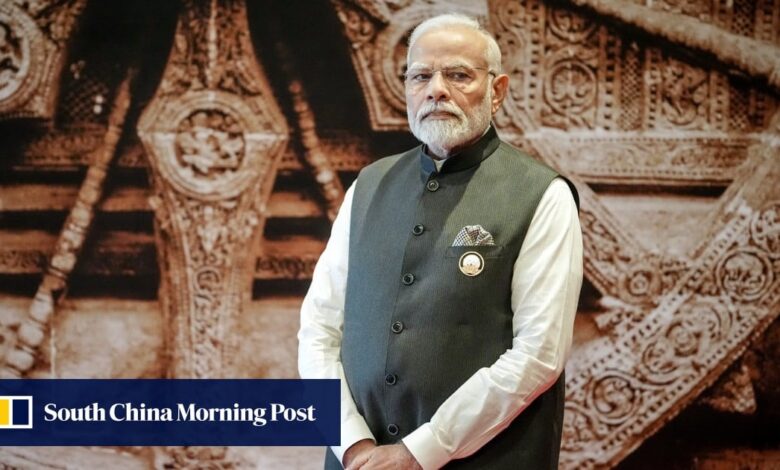

Is India’s Modi ‘clearly scared’ of opposition’s caste-census challenge ahead of state polls?

[ad_1]

His many references to Hinduism, India’s dominant religion, and touting of his government’s efficient administration have become hallmarks of the hugely popular leader’s whistle-stop electoral campaign over the past month.

But the BJP is facing a tough battle as India heads to the polls in five states – Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Telangana and Mizoram – ahead of national elections set to be held next year.

Can India’s Congress turn tables on Modi’s BJP on back of successful state polls?

Can India’s Congress turn tables on Modi’s BJP on back of successful state polls?

On Monday last week, India’s Election Commission announced a 24-day window – from November 7 to November 30 – for polls to held in the five states, with vote counting due to take place on December 3.

Around one-sixth of the country’s electorate will be eligible to cast a vote in the five state polls, three of which – Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh – are in the BJP’s northern and central heartlands.

Analysts say the BJP will have its work cut out for it, however, with splintered opposition parties uniting under the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (“INDIA”) and proposing a caste census that has the potential to divide the BJP’s Hindu vote bank.

The proposal for a caste census – aimed at collecting data on the percentage of the population that belongs to each caste and their economic status – has gained traction in recent weeks after the eastern state of Bihar, led by veteran politician Nitish Kumar of the Janata Dal (United) party who is seen as a potential candidate for prime minister, launched its own survey.

India’s constitution provides for no more than 50 per cent of government jobs and places in state-run educational institutions to be reserved for communities whose development has long suffered at the hands of elite castes.

Opposition parties say a new caste census is needed because marginalised communities now comprise more than 50 per cent of India’s population and should therefore have more jobs and school places reserved for them.

At present, 22.5 per cent of jobs and educational places in India are reserved for Scheduled Castes – a group also known as Dalits, or previously untouchables, who form the lowest socioeconomic rung of Indian society – while around 27.5 per cent are reserved for other historically marginalised communities that the government calls “Other Backward Classes”.

Weaponising the caste system

Rahul Gandhi, a senior leader in India’s main opposition Congress party, has said it will encourage caste surveys in states it controls to bring a new paradigm to India’s development, rather than push the old caste-versus-religion debate.

“We will not only implement the caste census, but also put pressure on the BJP and make them do it. If they do not then they should get out of the way,” Gandhi said. “We will also undertake an economic survey to show the ownership of wealth and assets [in different communities]. This X-ray is necessary.”

Other regional parties who are part of the opposition INDIA bloc are largely supportive of the measure, he said.

Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, a New Delhi-based writer and political commentator, said the issue could undermine what had seemed like unshakeable support for the BJP’s brand of Hindu nationalism, even though only the federal government can legally undertake a caste census.

“In the [state] assembly polls it may become an issue because caste conflict and caste divergences have been the BJP’s bugbear in forging Hindu unity,” he said.

In 2019’s parliamentary elections, the BJP won 303 of 545 seats in the lower house – a clear majority – after securing 37 per cent of the vote with the help of its staunch Hindu support.

India’s hate crimes are being logged, by exiles Modi’s BJP want silenced

India’s hate crimes are being logged, by exiles Modi’s BJP want silenced

Playing “the Hindu card” was the ruling party’s strongest move, Mukhopadhyay said, but “this vote bank can start breaking up if one Hindu starts looking at the other as someone who can take away his right to jobs and educational institutions” following a new caste census.

“Modi would not want divisions between Hindus along caste lines. He wants them to vote on the basis of Hindu unity,” he said.

There is precedent in India for a seemingly innocuous spark arising from the caste issue to catalyse into political upheaval. Former Prime Minister V.P. Singh’s government was ultimately brought down in 1990 by fierce opposition to his plans to reserve more government jobs for members of lower castes.

Analysts say the INDIA bloc could make inroads into the BJP’s voter base by drawing attention to welfare policies for the poor and other caste-based issues – citing recent losses in the Himachal Pradesh and Karnataka state polls that are likely to keep the ruling party on edge.

The Congress party realises that there is a possibility of focusing on the pro-poor vote

Sandeep Shastri, a political scientist who specialises in electoral studies, said Modi had been quick to point out following those defeats that the BJP’s vote share was only 1 per cent lower than that of Congress. But a closer look at the results reveals that the gap is 9 per cent among poorer voters.

“The Congress party realises that there is a possibility of focusing on the pro-poor vote,” said Shastri, adding that Modi had been trying to counter these efforts by addressing the audience at his speeches as mere parivar (my family) in a show of empathy.

State-level political leaders have also been working to woo the poorer sections of society with welfare measures.

Rajasthan Chief Minister Gehlot, for instance, has unveiled a gamut of programmes over the past year including free mobile phones for women, free electricity, discounted cooking gas, a generous medical insurance plan and a pension plan for government employees.

But the slew of incentives may not necessarily win votes, interviews with people on the streets of state capital Jaipur suggest.

“It is always great to get so many things for free, but I wonder why they are being given. I would rather vote for credible policies,” said Uttam Varshney, who has owned a small grocery shop in the city for decades close to the homes of political leaders.

Taxi driver Ramkesh said he was also pleased with the generous benefits, but had not decided which party would get his vote.

Others expressed dissatisfaction at the infighting between Gehlot and his deputy Sachin Pilot over the state’s top job, which they said had distracted the two Congress politicians from dealing with law enforcement problems, including the leaking of exam papers for government recruitment and high-profile bribery cases in which gold and cash was discovered in the offices of state officials.

Modi’s BJP has been quick to home in on this chorus of disappointment.

At a glittering public ceremony in Jaipur last month to mark the commencement of a public consultation exercise aimed at collecting policy suggestions, BJP President J.P. Nadda said Modi’s rule had ushered in a new style of governance in India.

“Our aim is not to have a political document, but our vision is to fulfil our promises,” he said, highlighting infrastructure development in the state over the past nine years spanning power grids, road projects and water pipelines.

“We would now like to invite all of them and say please do come,” he said, basking in the applause of hundreds of attendees that reverberated around the hall.

Formidable BJP machinery

Analysts say it will not be easy for the opposition to challenge Modi’s personal popularity and the BJP’s Hindu-nationalist platform, even if it scores victories in state polls based on local issues.

In state elections, regional Congress leaders such as Gehlot enjoy greater visibility on posters and placards than any of the party’s national leaders.

Despite soaring inflation, unemployment and other persistent problems, many Indians perceive the BJP to have a strong governance record.

“In the past, India was referred to as a golden bird. We are now seeing a semblance of its return to glory,” said Prem Krali, a farmer who lives in the outskirts of Rajasthan’s second-largest city Udaipur. “I will support anyone who works for the nation.”

But opposition politicians say the iron grip that Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah have over the BJP’s leadership puts the party at a disadvantage – an argument that was echoed by a section of voters who spoke to This Week in Asia.

Rajesh Kumar, who works at a pharmacist’s shop in Jaipur, said the BJP leadership had blundered by projecting Modi’s achievements instead of naming Vasundhara Raje Scindia, a former chief minister of the state who is of royal lineage, as its candidate.

“Who cares for Modi in state elections? People in the state would vote for Madam Scindia more than Modi because she knows our local problems,” he said.

Yet the BJP’s strategy has been to make Modi the face of its electoral campaign, analysts say, with regional leaders taking great care not to overshadow the prime minister despite internal tensions over the issue.

The ruling party will also have to overcome anti-incumbency sentiment, as only once in the past eight decades has an Indian political party won a third successive term: Congress under Jawahar Lal Nehru in 1962.

Analysts expect the BJP’s appeal to Hindu sentiment to influence the state polls in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, even though voters tend to attach greater importance to local issues in such elections.

Still, construction of the Hindu temple in Ayodhya was unlikely to influence many voters as the issue was over three decades old, according to Smita Gupta, an Indian journalist and independent political analyst.

Modi is clearly scared of the issue. He knows that if not handled well, this could go against him

Congress and the opposition INDIA bloc, meanwhile, “are going to try and amplify” calls for a new caste census ahead of the five state elections, Gupta said.

“Modi is clearly scared of the issue. He knows that if not handled well, this could go against him,” she said.

In an attempt to divert attention from the census – which could result in fresh demands for marginalised castes to get more reserved spaces in government agencies and educational institutions – Modi told an election rally in the southern state of Telangana earlier this month that southern India could lose 100 seats in India’s lower house of parliament if the census is carried out, Gupta said.

She said the prime minister had presented the issue as if it was an idea emanating from the opposition, rather than a constitutionally required exercise – that is not expected to happen until 2026 – to redraw constituency boundaries based on changing population densities.

Population growth in India’s southern provinces has lagged behind those in the north in recent years. These southern provinces, which form the hub of India’s tech talent, have long resented the greater representation enjoyed by the north in terms of parliamentary seats, Gupta said, and as fresh delimitation exercise will only widen this gap.

She said the BJP has been wrong-footed by the caste-census proposal as it could harm the party’s efforts to woo different castes separately.

A ‘loose’ opposition coalition

It remains to be seen whether Congress can use the caste issue effectively against the BJP, Gupta said. Among other issues, she said the opposition is also likely to shine a light on high youth unemployment that increased during the pandemic.

Urban unemployment stood at 6.6 per cent for the April-June period, according to the latest data from India’s National Sample Survey Office, down from to 7.6 per cent a year ago.

Analysts say it will not be easy for the opposition to take on the might of the BJP, which after two successive tenures in federal government has built a well-oiled electoral machine that spans offices and party members whose reach extends to practically every poll booth.

Even though Congress is in power in Rajasthan, a visit by This Week in Asia showed the party office in Jaipur to be almost devoid of staff while people thronged the BJP’s office.

This opposition alliance is a loose coalition of parties. They are only united by their opposition to the BJP

Mithun Vijay Kumar, an author and independent political analyst from the southern city of Kozhikode, called the opposition alliance too weak.

“This opposition alliance is a loose coalition of parties. They are only united by their opposition to the BJP. The common thing among them is the anti-Hindu agenda. This coalition will soon fall apart as soon as elections are over, whether they win or lose,” he said.

The INDIA bloc faces other significant challenges. It has yet to name a prime ministerial candidate or declare a seat-sharing arrangement so as to prevent a split in the vote.

Gupta said the alliance was only likely to arrive at a seat-sharing arrangement for next year’s national polls as Congress may get a bigger say if it manages to secure victories in the coming state elections. As for the alliance’s prime ministerial candidate, she said it is unlikely anyone will be named ahead of the general elections as it could be a deal-breaker.

West ‘created’ modern China by making it world’s factory, says India’s Rahul Gandhi

West ‘created’ modern China by making it world’s factory, says India’s Rahul Gandhi

“If the INDIA coalition really wins more seats than the BJP in the state elections, then a Congress leader will probably emerge as prime minister, as that party has a bigger footprint than any other in the opposition and therefore is most likely to win the largest number of seats for the alliance,” she said.

But even a strong opposition showing in the state elections is no guarantee of similar success in next year’s national elections, where Modi’s popularity will make more of an imprint.

“They [the BJP] have more money, a bigger propaganda machine, a stronger and better oiled organisation, and it’s one party. Something dramatic will have to happen for the BJP to lose power,” Gupta said.

[ad_2]

Source link