A One-Pan Meal of Sturgeon at the Dacha

Why are we so drawn to the countryside? A break from the hustle and bustle of the city? Fresh air? Yes, that’s all true, but we are also drawn to the dacha lifestyle, which is closely connected with food. Many of our compatriots love those long dacha lunches and dinners.

In Russia people’s obsession with dachas appeared — somewhat surprisingly — in the 19th century. That was when the idea of a “dacha” became relevant — after the abolition of serfdom (in 1861) and the disappearance of enormous private farm estates. Of course, the term existed before. It’s from the word давать (to give). For more than 150 years, dacha estates were the privilege of the aristocracy, “given” by the tsar for a service or merit.

Greenhouses with exotic plants were an integral part of a nobleman’s estate. Many owners kept greenhouses to grow fresh herbs, cucumbers and, of course, exotic vegetables to amaze their neighbors. And the owners of estates did not consider it shameful to work on them. As a rule, greenhouses were built of wood; stone cellars were built for growing seedlings.

For many noblemen, vegetable growing was a serious hobby and sometimes one of the few pleasures in life. This was especially true of the Decembrists (the insurrectionists of 1825) who were exiled to Siberia.

Decembrist Vladimir Rayevsky was the first in Irkutsk province to grow gourds and melons. In a letter to a friend he reported that he would harvest “an average of more than 150 excellent watermelons and up to 100 melons every year.”

Courtesy of the authors

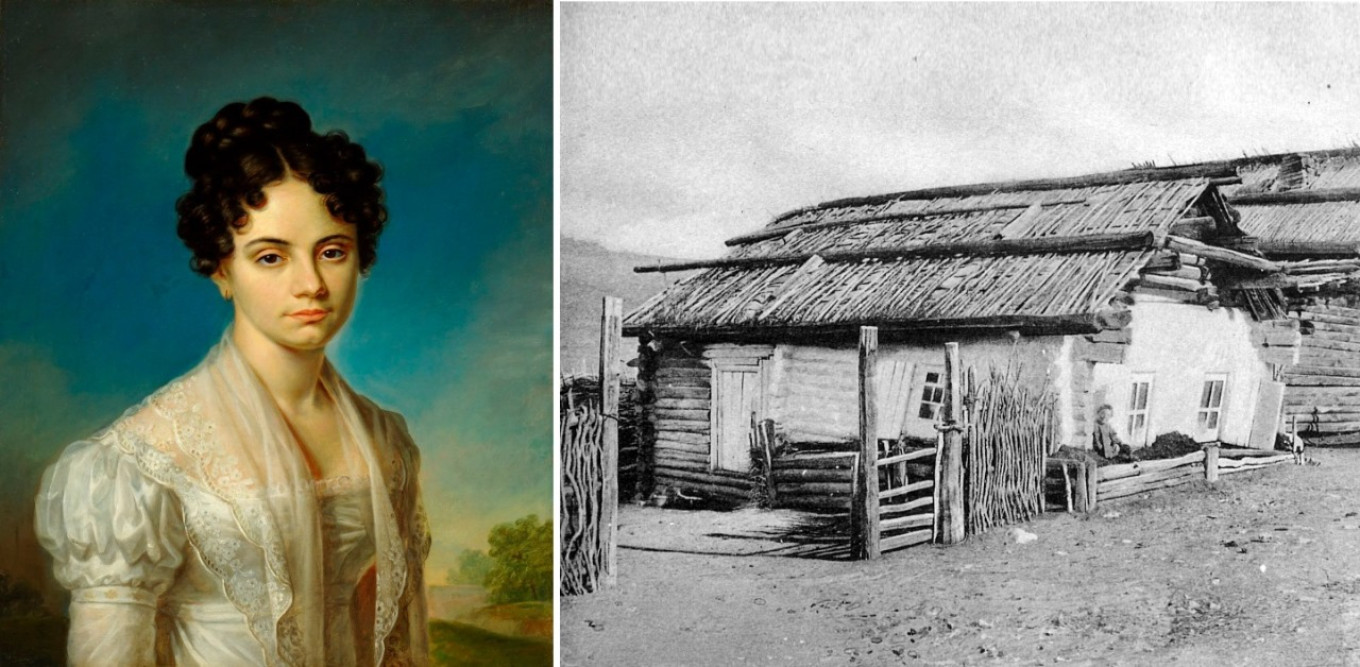

Princess Maria Volkonskaya (wife of Decembrist Sergei Volkonsky) was one of the first in Eastern Siberia to plant tiny carrots, dwarf beans, tomatoes, maize, celery, spinach, purslane and tarragon. She grew four kinds of melons: “Honeydew, Standard, Cantaloupe and Persian.” She and her husband even built a small greenhouse in the yard of the Chita stockade and taught her friends “to grow a vegetable garden.”

The princess sowed cucumbers with her own hands on raised manure beds in the yard behind the stables. She protected the beds from frosts, which occurred even in July, with “felt and carpets.” “I have,” she wrote to her mother-in-law in the fall of 1829, ”cauliflower, artichokes, beautiful melons and watermelons and a stock of good vegetables for the whole winter.” Records show that Maria put up 50 barrels of pickles.

Wikimedia Commons

But life goes on, and noble estates were replaced by more “democratic” houses, which were rented or built by ordinary people — doctors, teachers and merchants. “The New Dacha” is the title of one of A.P. Chekhov’s stories. “They bought twenty dessiatins (54 acres) of land, and on a high bank in a clearing where cows used to roam they built a beautiful two-story house with a terrace, balconies, a tower and spire, then planted large trees all winter. When spring came and everything turned green all around, the new estate already had leafy alleys and a gardener with two workers in white aprons digging near the house.”

At the end of the 19th century people of almost every income could afford some kind of dacha. Most often people didn’t buy or build their own house. The “third estate” — low-level officials and clerks — rented country houses and left the city to spend the summer there.

Dacha culture plays a very special role in Russian pre-revolutionary mentality. Evenings around the table with friends and neighbors were the image of country life. An important part of dacha life was eating well based on local products grown right at the dacha or in the surrounding farms. The Finnish or Estonian milkmaid who left milk, butter or sour cream on the doorstep of the dacha was an essential figure in the memories of many Russian intellectuals of the early 20th century.

Courtesy of the authors

The dacha was a kind of continuation of estate culture. By the end of the 19th century, many estates had lost their “nobility.” Chekhov’s Melikhovo is the most striking example of this. This was when healthy eating and proper farming were the hot trends among Russian enlightened society. Sprawling apple orchards still adorn the estate, and Anton Pavlovich’s experiments in growing artichokes were not wasted. Even today these exotic cones ripen near the house every summer.

There was hardly anything these farmsteads and cottages didn’t grow. Ivan Fyodorovich Tyutchev, the youngest son of the great poet, even cultivated pineapples at Muranovo near Moscow. Shchi with pickled pineapples was a traditional treat in his hospitable house.

Courtesy of authors

Summer at the dacha was already a tradition for many townspeople. A leisurely, measured way of life was very attractive to urbanites — the kind of life that was almost impossible to live amid the capital’s hustle and bustle. It was also a historical ideal, baked into the genes of the Russian people. After all, even Russian cuisine cannot be rushed. Food is cooked for a long time, and dishes are consumed slowly and with pleasure over long conversations around the table.

Indeed, food has always been one of the main benefits of dacha life. Virtually everything is right there: fruits and vegetables in the garden; tender herbs growing all around, wherever you look. Catch bream in the morning and you’ve got soup for lunch. In the evening you can bake delicious pies with the mushrooms you picked the day before. And on top of all this, there is the pleasure in knowing that you’re living the the life of the “simple folk” made popular by Leo Tolstoy. In the early 20th century this was very appealing to Russian educated classes.

Wikimedia Commons

But life doesn’t stand still. Today the dacha is returning to its pre-revolutionary incarnation for many people. With it comes interest in neighboring farmers and the food produced on their farms along with local culinary spcialities and even the past itself, which we want to believe was very pleasant and dignified with delicious food.

Here is a dish that combines old-world luxury with the classic foods of today’s “everyman” dacha. In Russia it’s called Sturgeon à la Viardot. We have found no connection to Ivan Turgenev’s muse, the French actress Pauline Viardot. It is probably just a beautiful legend invented by a woman looking for a way into a man’s heart. After all, a short cut through the stomach often works very well.

Sturgeon à la Viardot

Ingredients

- 2 large sturgeon steaks, big enough to be cut in half

- 1 medium onion

- 1/2 medium carrot

- 1/2 sweet red pepper

- 100 g (3.5 oz or a generous cup) mushrooms

- 4 small pickled cucumbers

- 1 medium red tomato

- 4 Tbsp vegetable oil

- salt to taste for mushrooms

- 100 g (3.5 oz) cheese (such as Valio Oltermanni, Gruyere or Gouda)

- 4 Tbsp mayonnaise

Instructions

- First of all, prepare the garnish for the fish. Finely dice the onion, cut the carrots, pepper and mushrooms into small pieces, more or less the same size. Cut the gherkins in half lengthwise. Cut the tomato in half and then into 8 thin slices. Grate the cheese on a coarse grater. After all the preparatory work is finished, start frying.

- Put 2 frying pans on the stove. In one heat up some of the oil and first sauté the onion to a golden color, then add the carrots and finally the pepper. Sauté it all together for about five minutes.

- Meanwhile, in the second frying pan sauté mushrooms until done in a small amount of oil and then salt them lightly at the end.

- Combine the contents of both pans, stir and set aside.

- Heat the oven to 200°C/390°F.

- Now wash the fish well, if there is skin, remove it, divide in half and dry both pieces with a towel. Heat oil in a frying pan and fry the fish on both sides for 3 minutes each. Do not salt; the pickles will be salty enough.

- Lay the sturgeon steaks on a baking tray. Top each steak with the mixture of onions, carrots, peppers and mushrooms. Then place on top of each piece 2 slices of gherkin, and on top of that 2 slices of tomato. Baste with good mayonnaise (in Russia it is customary to bake it), sprinkle with cheese and put in the oven for about 20 minutes.

- You don’t need anything as a side dish, since it has everything in it. You can serve it from baking tray or plate it.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office has designated The Moscow Times as an “undesirable” organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a “foreign agent.”

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work “discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership.” We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you’re defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.