Kazakh Researcher Discusses Water Scarcity, Regional Cooperation Mechanisms

ASTANA—The future of water in Central Asia may look grim – rapidly growing population, climate change, and add inefficient water use to that. But regional cooperation, though varied, gives hope. In an interview with The Astana Times, Zhaniya Khaibullina, a water security researcher at the Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, discusses water management issues, the legacy of the Aral Sea crisis, and regional cooperation mechanisms.

Zhaniya Khaibullina. Photo credit: Khaibullina’s personal archive

Pressing water-related issues

The region’s economic development hinges on water, which is becoming scarce. Two main rivers – Amu Darya and Syr Darya – feed the region. The Amu Darya begins in the Pamir Mountains, while the Syr Darya has its source in the Tien Shan Mountains.

Most water resources are directed to irrigation purposes, but because of the wear and tear of irrigation canals, the region faces significant losses. In Kazakhstan alone, the figure reaches 40%, according to the data from the Ministry of Water and Irrigation.

Increasing water withdrawals and constrained water resources significantly strain the region’s water supply.

“From my perspective, the most pressing water-related issue that needs immediate attention in Kazakhstan and Central Asia is water scarcity and governance, particularly in light of the Aral Sea catastrophe and its implications for the Central Asian countries in the Aral-Syrdarya basin where I have been for a field research trip and conducted 120 interviews in 15 settlements [auls],” said Khaibullina, who is researching water security in Central Asia.

Situated between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the Aral Sea has been dramatically shrinking since the 1960s when Soviet planners diverted the two rivers that fed it, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, to irrigate the arid lands.

What many experts deem as the Aral Sea disaster is a stark reminder of the consequences of unsustainable water management and agricultural practices. The sea began to shrink at an alarming rate, destroying the once-thriving fishing industry and affecting local communities and their source of income.

There were tiny signs of hope, including the construction of the Kok-Aral Dam in 2005 by Kazakhstan, with assistance from the World Bank, which led to a partial recovery of the Northern Aral Sea. The Northern Aral Sea has recently seen an increase in its water volume, with 1.1 billion cubic meters entering its basin, bringing the total volume to 21.4 billion cubic meters.

Kok-Aral Dam. Photo credit: Brigitte Brefort, World Bank

Khaibullina stressed the “critical importance of addressing the legacy of the Aral Sea disaster and its impact on the region.”

“The shrinking of the Aral Sea, once the fourth-largest inland body of water in the world, has led to the exposure of toxic chemicals and salts, causing environmental degradation and health hazards for local communities. Moreover, the depletion of the Aral Sea has significantly affected the climate, agriculture, and biodiversity in the region, exacerbating water scarcity and socio-economic challenges for countries like Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan,” she said.

In her research, Khaibullina suggests using the One Health approach. This collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary strategy recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health. When applied to water, this approach emphasizes the critical role of water quality and management in maintaining the health of ecosystems, animals, and humans.

Impact of water scarcity on local communities

“In rural areas, where agriculture is a primary livelihood source, water scarcity can directly impact agricultural productivity and food security,” she explained. Farmers depend on water for irrigation to cultivate crops, and limited access to this vital resource can result in reduced yields, crop failures, and livelihood insecurity. This situation often leads to food shortages, income losses, and increased dependency on external assistance.

Khaibullina highlighted that water scarcity significantly affects access to clean and safe drinking water. In rural communities facing contaminated or scarce water sources, residents may be forced to travel long distances to fetch water or resort to unsafe alternatives.

According to the World Bank, nearly one-third of the population in Central Asia, or nearly 22 million people, lack access to safe drinking water.

Syr Darya is the longest river in Central Asia. Photo credit: Elena Karaban, World Bank

“This can lead to waterborne diseases and health complications,” she added, emphasizing that women and children, who typically bear the responsibility for water collection, are particularly vulnerable.

“Water scarcity can contribute to conflicts and tensions within communities over access to limited water resources. Competition for water can strain social relationships, exacerbate inequalities, and create additional stress on already vulnerable populations,” said Khaibullina.

She mentioned several water supply programs in Kazakhstan that aim to address water scarcity and improve access to clean and safe drinking water.

“Two notable programs, Drinking Water, Ak Bulak, and Nurly Zhol, aim to enhance water infrastructure, promote sustainable water management practices, and improve water supply services for communities nationwide. Official statistics indicate that coverage has now reached 90-95%,” she said.

However, challenges persist. “In 2021, in rural areas such as the Akbulak settlement, residents continue to encounter difficulties. For instance, individuals must pool funds to hire water carriers, which results in shared water usage for various purposes like laundry, sanitation, and meal preparation for 20 to 30 days,” she explained.

Impact of climate change

Water security concerns are growing with climate change, which impacts Central Asia’s water resources in several ways.

“This includes changes in precipitation patterns, increased evaporation rates, glacier melting, and altered river flows, resulting in shifts in water resources across Central Asia. Recent observations show several noteworthy trends related to climate change and water resources in Kazakhstan and Central Asia. These trends encompass variations in precipitation patterns, fluctuations in snow and rainfall, and heightened variability in water availability for agriculture, industry, and human consumption,” said Khaibullina.

Tajikistan has the highest number of glaciers in Central Asia. Photo credit: ca-climate.org

Melting glaciers and reduced snowpack in the Tien Shan and Pamir Mountains decrease the long-term availability of water, as these are crucial sources for rivers like the Amu Darya and Syr Darya.

Increased temperatures ultimately lead to higher evaporation rates, reducing water levels in rivers and lakes. “This escalated evaporation can further strain water resources, resulting in decreased soil moisture levels and reduced water availability for agricultural activities and ecosystems. Overall, the observed trends underscore the intricate relationship between climate change and water resources in Kazakhstan and Central Asia,” Khaibullina explained.

“Given the ramifications of climate change on water availability, countries must integrate climate adaptation measures into their water governance strategies. This may involve the development of resilient infrastructure, diversification of water sources, and advocacy for water conservation practices,” she said.

Current cooperation mechanisms in the region

Cooperation on water issues among Central Asian countries features bilateral and multilateral agreements and regional organizations.

Several fundamental agreements on water management exist in Central Asia, including the 1992 Agreement on Cooperation in the Joint Management of the Use and Protection of Water Resources of Interstate Sources and the 1998 Framework Agreement on the Syr Darya Basin.

The 1992 agreement established the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination, a regional body managing and coordinating the use of shared water resources. It recognized “equal rights to water use and responsibility to ensure rational use and protection of water.”

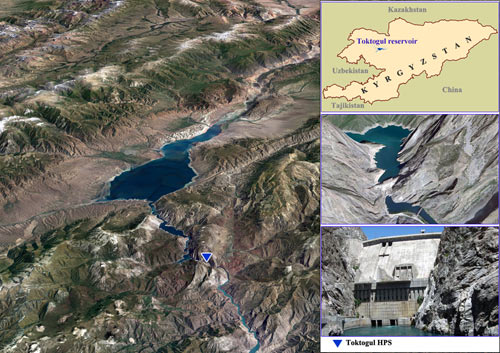

Toktogul Reservoir is one of the water reservoirs on Syr Darya. It is located on the Naryn River, the principal source of the Syr Darya, in the Jalal-Abad Region in the Kyrgyz Republic. Photo credit: icwc-aral.uz

The 1998 agreement involved Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Uzbekistan and was later joined by Tajikistan. The agreement sets protocols for annual water release schedules from reservoirs, primarily managed by the Kyrgyz Republic, to ensure downstream countries—Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan—receive adequate water for irrigation. It also envisions a compensation mechanism where downstream countries provide financial or energy resources to upstream Kyrgyzstan to regulate water releases and maintain reservoirs.

Another key cooperation mechanism is the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS). Established in 1993, IFAS is a major regional organization that aims to address the Aral Sea’s environmental crisis and improve water management practices. Kazakhstan is chairing the IFAS in 2024.

In recent years, water issues have gained the upper hand in discussions among Central Asian leaders, including during their regular consultative meetings.

“The current mechanisms of cooperation between Central Asian countries concerning transboundary water sources have shown varying degrees of effectiveness,” she said.

Khaibullina noted persistent challenges and areas requiring enhancement to strengthen regional water cooperation.

“Despite these mechanisms, issues related to implementation and enforcement persist. Disputes surrounding water rights, infrastructure projects, and the impacts of climate variability have, at times, strained inter-country relations. Deficiencies in trust, transparency, and data exchange have impeded effective collaboration on water governance,” she explained.

She pointed out the need for enhanced trust and communication when asked how regional cooperation can be improved. The countries also need to reinforce existing legal frameworks and agreements, such as those under the auspices of the IFAS.

“Adherence to international water conventions and treaties can help resolve conflicts and ensure sustainable water resource management. There are organizations working by IFAS, such as the Regional Center of Hydrology, where disaster-risk reduction activities were implemented,” she added.

Youth involvement

Khaibullina sees it imperative to involve youth in water management initiatives through educational programs, leadership opportunities, or awareness campaigns.

One example of such an effort in Central Asia is the United Central Asia Professionals (UCAP), a network of young scientists, water specialists, and experts.

With the support of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, the German Embassy and Perspectivity Enterprise of the Netherlands, the network organized talks and discussions with youth in Shymkent, Oskemen, Karagandy, and Taraz.

Participants of Climate Dialogue event in Shymkent on July 3. Photo credit: UCAP Instagram account

Climate Talks will be held in Atyrau on Aug. 19-20 and in Aktau on Aug. 21-22 to explore the water situation and climate policies in Kazakhstan.

“Embracing an integrated water management approach that accounts for the requirements of all stakeholders, including upstream and downstream nations, is critical. Prioritizing sustainable water utilization, ecosystem conservation, and climate resilience is paramount,” said Khaibullina.