Will China’s belt and road plan, Asean provide silver lining as US step ups de-risking and trade prospects dim?

[ad_1]

In the same period, exports to the European Union dropped by 2.6 per cent, while shipments to the US fell 13 per cent.

This shift has resulted in Mexico and Canada replacing China as the biggest exporters to the US this year.

And according to the US Commerce Department, the US imported 25 per cent less from China in the first seven months of the 2023, year on year, the equivalent of around US$203 billion in goods.

[My] guess is that most of China’s exports to Asean members … are not actually destined to remain in the Asean

The belt and road plan was launched in 2013 as a way of enhancing China’s trade links with the world and expanding its global influence, and to date, 152 countries have joined the initiative, including the 10-members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean).

But analysts have warned that the recent shift would not be enough to offset the losses from a decline in trade with the West even with the Asean bloc cementing its place as China’s largest trading partner.

“[My] guess is that most of China’s exports to Asean members … are not actually destined to remain in the Asean,” said Deborah Elms, the founder and executive director of the Singapore-based Asian Trade Centre.

“Instead, they are either intermediate goods for assembly into goods that are either sent to China for any final processing or to the US and Europe for final sale.

“If this is true, then it’s not quite accurate to say that [Belt and Road Initiative] exports will ‘take up the slack’ for US or EU exports. Instead, they may be a substitute for direct exports to both final markets.”

The combined value of China’s trade with Asean countries in June stood at US$77.4 billion, making it China’s biggest trading partner compared to its US$68.8 billion trade with the European Union and US$55.7 billion with the US.

Asean countries made up 15.8 per cent of China’s exports, while the European Union made up just 15.5 per cent of China’s total export value in June.

The changes in China’s export profile have raised an imminent question at a time when it is struggling to boost its post-Covid economic recovery.

China’s exports to remain weak until 2024: 4 takeaways from July’s trade data

China’s exports to remain weak until 2024: 4 takeaways from July’s trade data

This marked the largest contraction since the start of the coronavirus pandemic after falling at the fastest pace since February 2020.

Compared to the same period last year, China’s overall export value from January to July grew by just 1.5 per cent in yuan terms, but fell by 5 per cent in US dollar terms due to the depreciation of yuan against the US dollar.

Last month, the Chinese currency weakened to the lowest level against the US dollar since the global financial crisis in 2008.

Only doing business with developing and third world nations is very risky

“Only doing business with developing and third world nations is very risky,” Mao Zhenhua, co-director of Renmin University’s Economic Research Institute, said in an article published last month.

“We see that Asean countries are increasing their exports to the US and Europe, and increasing their imports from China.

“This trend means that there is a potential shift of supply chain ongoing. If this goes on long term, it is a disadvantage for China’s exports, and so we need to continue expanding our trade with European countries.”

And if the shift continues, China could be cut off from the lower end of the supply chain and be gradually replaced by countries that once served as re-export hubs for goods, add Mao, who is also the co-founder of China Chengxin Credit Management.

China must step up economic fight with US in key Asean battlefield: economist

China must step up economic fight with US in key Asean battlefield: economist

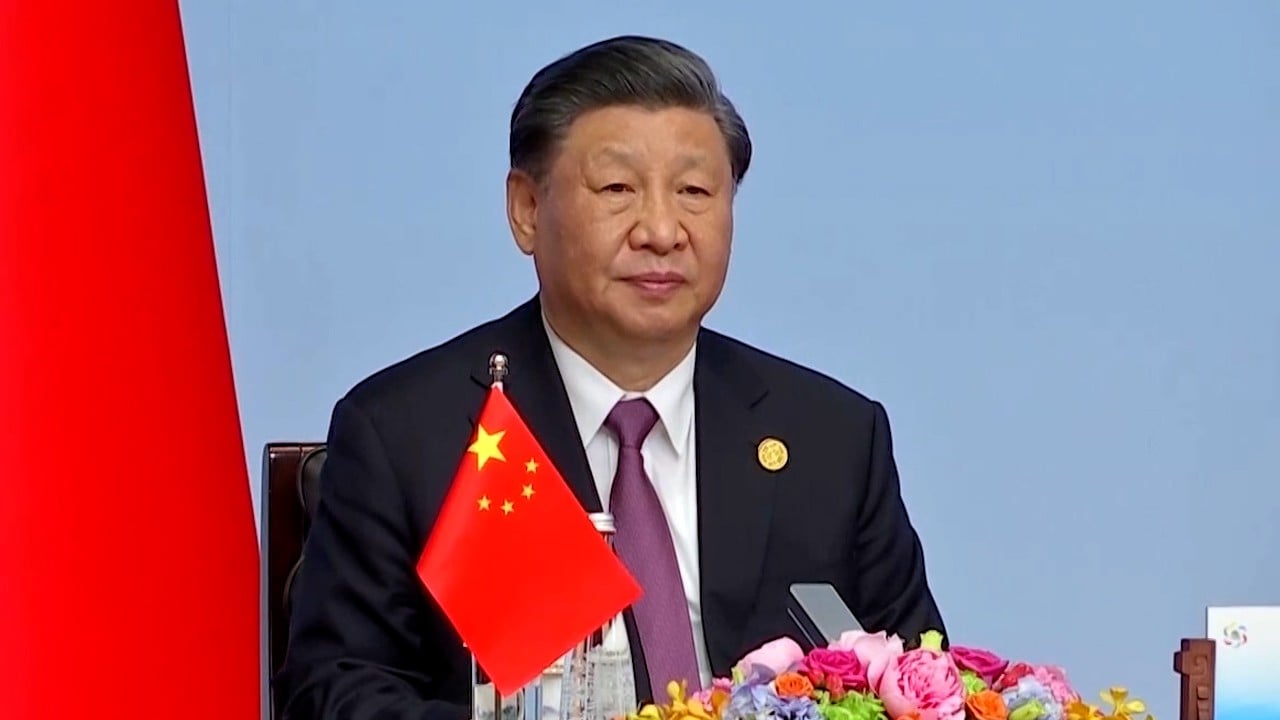

The multibillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative, launched by President Xi Jinping in 2013 with the aim to improve China’s connectivity with the world via infrastructure and investments, will celebrate its 10th year anniversary in October.

But the project has long been criticised as a tool for China to spread its geopolitical and financial influence through binding emerging countries to so-called debt-trap diplomacy where countries are left with loans that cannot afford to repay.

And the opaqueness of China’s official statistics have also made the definition of what Beijing calls “countries along the Belt and Road” even more vague.

Of the 152 countries listed as having signed memorandums of understanding, 52 are in Africa and 40 are in Asia, with the others across the Middle East, Latin America and Europe.

But it is unclear whether Beijing uses the 152 countries as a base for their calculations for trade with countries that have signed up to the belt and road plan.

Before departing on his trip, Tajani said the plan had not brought the results Italy had expected, and while Rome would like to work with Beijing, they want a level playing field.

South Korea, Vietnam, Russia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates, the Philippines and Saudi Arabia were China’s top belt and road export destinations in the first half of the year, according to the Post’s calculation from trade data available on Chinese data provider Wind.

In the short-run, I expect that Chinese exports to the markets of industrialised countries will continue to decrease

And with six of the leading nations part of the 10-member Asean bloc, the figures also match the fall in China’s exports to the group in US dollar terms, which fell by 6.7 per cent in the first half of the year compared to the same period last year, a drop which has been widening every month.

“China was the global centre of manufacturing. Now, because of concerns about national security and the resilience of supply chains, multinational corporations, which are the lead firms of global value chains, have been diversifying supply chains away from China,” said Xing Yuqing, an economics professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo.

“In the short-run, I expect that Chinese exports to the markets of industrialised countries will continue to decrease.

“Whether its exports to [Belt and Road Initiative countries] could maintain the growth momentum depends on its investment in those countries.”

Chinese merchants ‘doing quite well’ in Russia as Western sanctions take toll

Chinese merchants ‘doing quite well’ in Russia as Western sanctions take toll

Russia has seen the biggest increase, rising from the eighth largest destination to the third in a year.

Bilateral trade between Russia and China totalled more than US$114.5 billion from January to June, representing a 40.6 per cent year-on-year increase, while China’s exports to Russia increased by 78.1 per cent during the same period.

Trade ties have increased since Russia was sanctioned by many Western economies after its invasion of Ukraine in February last year, creating opportunities for both nations to increase trade.

And according to Xing, it is still important to “diversify China’s export market into [Belt and Road Initiative] countries to hedge the weak demand from the US, Japan, and European countries”.

“But, I do not think the growth in [Belt and Road Initiative] markets can offset the fall in the industrialised countries,” he added.

Chinese projects overseas would also increase purchases of Chinese goods and machines, he added, as firms would still be using materials from China.

While shipments to belt and road countries have been outperforming China’s average export growth, the increases have already slowed in line with China’s overall exports.

In the first quarter of 2023, year-on-year growth of China’s export value to belt and road countries stood at 13.6 per cent.

The growth, however, has already slowed in the second quarter of 2023, falling to just 1.9 per cent compared to 2022.

What sells well in the US or Europe may not sell particularly well, or at the same level of quality and price point

Compared to the first quarter, trade value in the second quarter also slowed by 4.1 per cent.

But there has, according to Chinese customs, been a “closer industrial cooperation” between China and belt and road countries, as highlighted by the type of goods exported.

China’s exports of intermediate goods for car production – in terms of car parts, lithium batteries and parts for data processing – to belt and road countries increased by 39.3 per cent, 34.3 per cent and 28.9 per cent, respectively, year on year, in the first half of the year.

But while a supply chain shift means that China would be able to find new market opportunities in previously unexplored or underdeveloped markets, Elms said that “the basket of goods on demand might be different”.

“What sells well in the US or Europe may not sell particularly well, or at the same level of quality and price point, as something sold to, say, Asean or Russia,” she added.

Additional reporting by Ji Siqi

[ad_2]

Source link