Indonesia election 2024: who are the 3 candidates vying to lead the world’s third largest democracy?

If Prabowo wins the presidency on Wednesday, it will be the culmination of a military and political career spent fighting to influence the future of his country. After graduating from the Indonesian Military Academy in 1970, Prabowo served in the Special Forces (Kopassus) before being tapped to lead the Strategic Reserve Command (Kostrad) in 1998.

Indonesia’s Prabowo takes flak for ‘slow brains’ remark in final election debate

Indonesia’s Prabowo takes flak for ‘slow brains’ remark in final election debate

That same year also saw the economic and political crisis that led Prabowo’s father-in-law at the time, President Suharto, to resign after 32 years of dictatorship. Around the time of the riots that precipitated Suharto’s ouster, troops under Prabowo’s command kidnapped and tortured at least nine democracy activists. Prabowo acknowledged responsibility for the kidnappings and was dishonourably discharged from the military.

He was also banned from the United States for decades due to alleged human rights abuses, including military crimes during the occupation of East Timor, but the ban was lifted in 2020 after Widodo named him defence minister.

After the end of his military career, Prabowo focused on politics, forming the Great Indonesia Movement (Gerindra) party in 2008. In 2009, he ran as the vice-presidential candidate to Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) chairwoman Megawati Soekarnoputri, but they were defeated by incumbent president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

The populist: Ganjar Pranowo

With the backing of the ruling (PDI-P), Ganjar Pranowo was tipped early on to be the man to beat in this week’s election. But President Widodo’s decision to break from his party and tacitly throw his support behind Prabowo and his son has led to Ganjar languishing in the polls. However, a growing backlash against Widodo’s alleged machinations may give Ganjar the late boost needed to force a run-off.

In many ways, Ganjar cuts a similar figure to Widodo. Neither one comes from the military or one of the elite political families that dominate so many of Indonesia’s seats of power. Like Widodo, he is known for being a man of the people, with an easy-going manner and a propensity for making informal, impromptu visits to talk to his constituents.

Can Indonesia’s Ganjar force a run-off as bid for ‘total victory’ dries up?

Can Indonesia’s Ganjar force a run-off as bid for ‘total victory’ dries up?

After serving in the Indonesian House of Representatives (DPR) for a decade, Ganjar won the governorship of Central Java in 2013 on a platform focused on policies aimed at helping the poor, such as financing loan reform that helped drive down interest rates on microloans. He is also known for his anti-corruption efforts, with his commitment to cracking down on bribery leading to the Corruption Eradication Commission awarding the Central Java government an award in 2015.

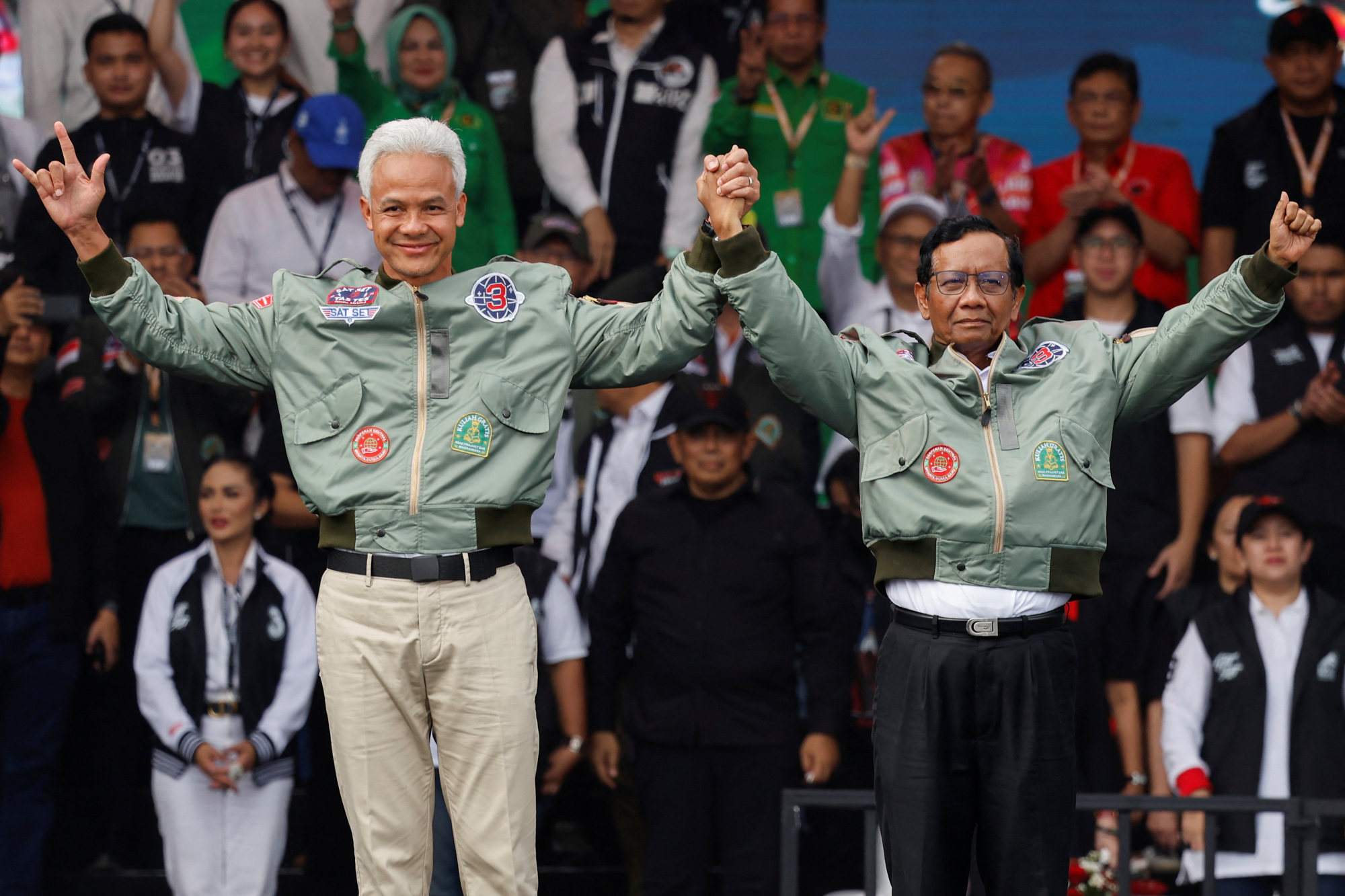

Ganjar’s running mate is Mahfud MD, who recently resigned as coordinating minister for political, legal, and security affairs over his disagreement with President Widodo taking sides in the presidential election. He is a respected legal scholar who has also served in a number of senior government roles, including head of the Constitutional Court and minister of law and human rights under previous administrations.

However, the polls indicate that not even rock stars could elevate Ganjar into first place at this point. His only realistic hope is that he and his other rival, Anies Baswedan, are able to hold Prabowo under 50 per cent and force a run-off.

Will Indonesia’s Anies and Ganjar team up to deny Prabowo an outright poll win?

Will Indonesia’s Anies and Ganjar team up to deny Prabowo an outright poll win?

The opposition: Anies Baswedan

While both Prabowo and Ganjar essentially promise to deliver continuations of Widodo’s popular policy agenda, Anies Baswedan has sought to reach voters looking for a change from the status quo with promises to reverse some of the president’s more controversial policies. He is running as an independent candidate backed by the Coalition of Change for Unity, a group made up of three political parties: NasDem, the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), and the Democratic Party.

Anies first made a name for himself as an academic, becoming the youngest rector in Indonesia at 38 years old when he was tapped to lead Paramadina University. He gained national recognition soon after by developing the successful Indonesia Mengajar (Indonesia Teaching) programme that sends university graduates to teach at underserved schools across the archipelago.

He eventually left academia to pursue a career in politics. In 2014, he joined Widodo’s first presidential campaign as an official spokesperson and, after their win, he was named minister of education and culture, serving for two years before being replaced – allegedly for not fulfilling Widodo’s policy priorities.

In 2017, he entered the national spotlight by joining the race to become the governor of Jakarta, challenging the incumbent Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, better known as Ahok. Before Widodo won the presidency, Ahok had been his vice governor and was well regarded as a tough but progressive leader. However, after the ethnic-Chinese Christian politician was accused of blasphemy for referencing the Koran in one of his campaign speeches, Anies seized on the line of attack and aligned himself with hardline Islamists who held massive rallies denouncing Ahok. Anies won the governorship, and Ahok was found guilty of blasphemy and jailed for nearly two years.

Could Indonesian conservative Anies Baswedan be nation’s next president?

Could Indonesian conservative Anies Baswedan be nation’s next president?

Anies continues to be aligned with conservative Islamic political factions, who have often played the role of the opposition during Widodo’s decade in office. His running mate Muhaimin Iskandar, also known as Cak Imin, is the chairman of the Islam-based National Awakening Party (PKB).

Play with Welcome Bonus Up to 300%

Play with Welcome Bonus Up to 300%