New Delhi’s oldest bookshop retains ‘poetic chaos’ and timeless charm: ‘here, books find us’

[ad_1]

In New Delhi’s fast-evolving Khan Market, the Faqir Chand Bookstore is like a space frozen in time.

“They must have had a passion for reading, because after surviving something as disastrous as the Partition, they still had the courage to open a bookstore and not something that’s easier to sell,” said Abhinav Bamhi, 26, Faqir Chand’s great-grandson and a fourth-generation custodian of the shop.

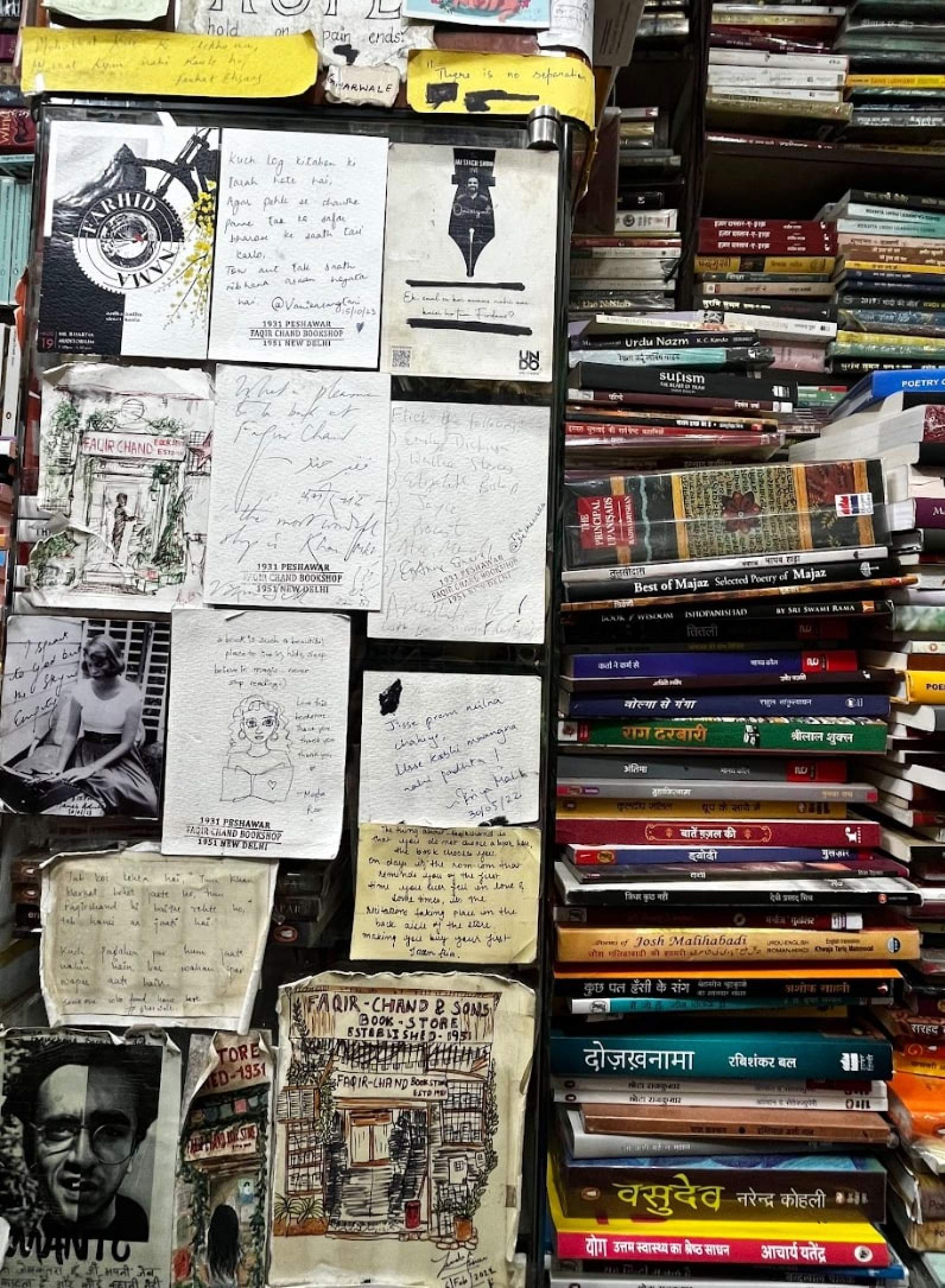

Bamhi has been a part of that change but said he finds solace knowing that the bookshop is one place where “time has stopped”. The subtle shade of yellow in its shutters, the font of the store’s name, and the maze of books inside the 1,500 square feet area (138 square metres), are all tinged with nostalgia for Bamhi and others who have frequented the shop for decades.

For writer Mayank Austen Soofi, who chronicles the city and its people in his blog The Delhiwalla, the bookshop is “a foothold to stability in the furiously transforming Indian capital”. He added that the shop and its owners offer a contrast to the stereotypical “social comedy of the upper classes” in Khan Market.

“It is a tangible space linking us to times gone forever, but whose histories continue to aggressively shape our present,” he said. “At a time when we all are digging deeper into our echo chambers, here’s a bricks-and-mortar space in the real world giving a safe space to all.”

‘Poetic chaos’

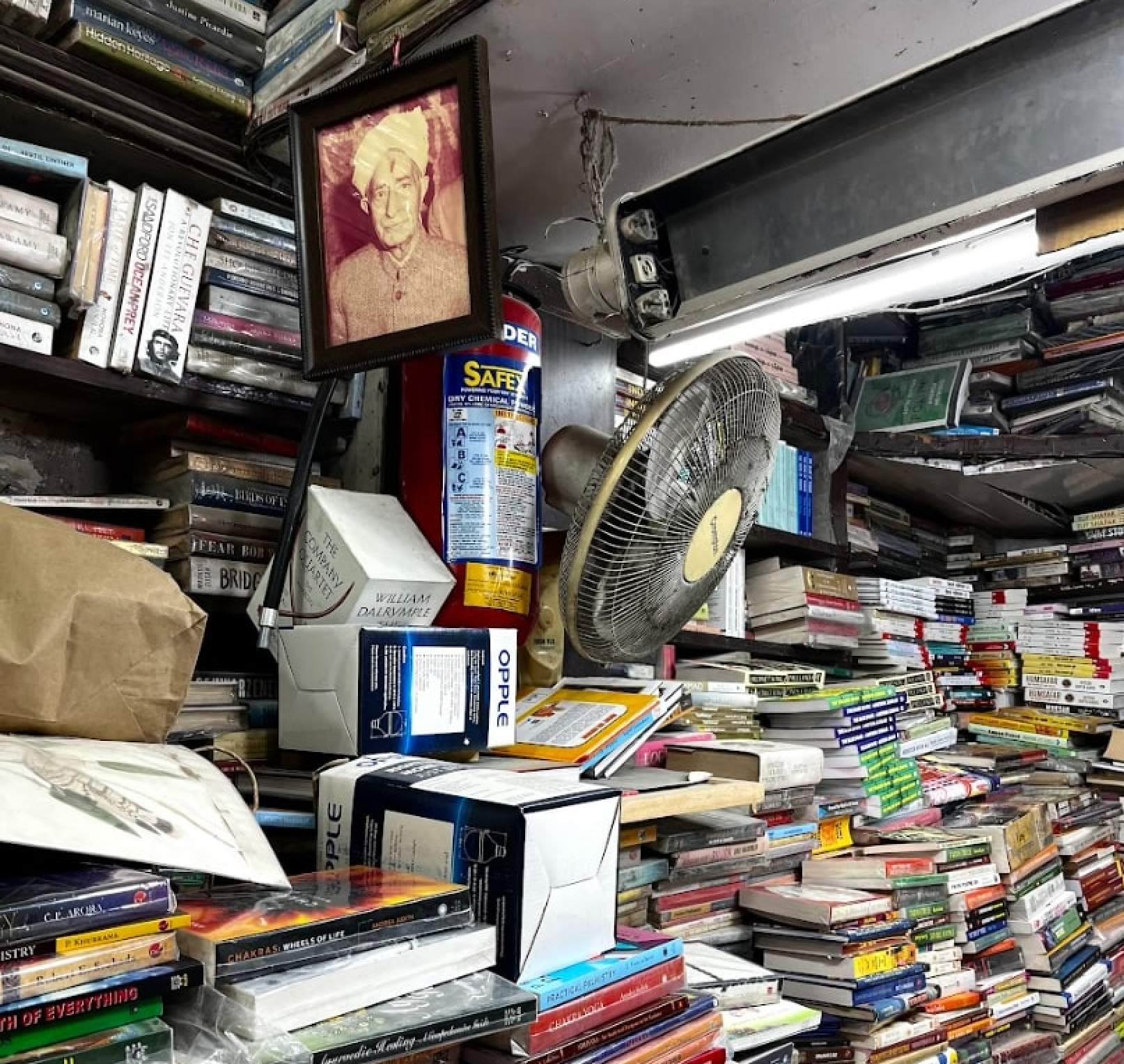

Faqir Chand Bookstore is an iconic address and an institution in itself, which Bamhi sees as “a part of the city’s culture” where noted authors and historians come searching for books. But finding a book there is not easy. The store lacks computers – or any trace of modern-day technology, except the payment machines – to help locate books from the piles, although Bamhi and his two store assistants are quick to spot them.

“Here, books find us – we know what’s where,” he said. “It’s a poetic chaos.”

And perhaps it is the chaos that attract readers like history student Ramya Ramanathan, 20, who likes the “haphazard nature” of the shop and was drawn to its history and legacy.

“You become tired buying books online,” she said. “For many commercial bookshops, it’s just business, but I can sense the emotional attachment here.”

Bamhi, who runs the bookshop with his parents, said the family does not want to expand or sell books online despite growing competition, adding they will continue Faqir Chand’s legacy.

At Khan Market, only a few family-run businesses have survived, including Bahrisons Bookseller, which was opened two years after Faqir Chand, in 1953, though it has expanded and adapted to the current times.

“They are family friends, so there’s no rivalry – it’s a healthy competition,” Bamhi said. “Having two strong independent bookshops in one market brings more people [here].”

On a recent December afternoon, a steady stream of people posed for photos outside Faqir Chand as young readers squeezed through the narrow passage in between the books, scanning for titles before finally giving up and asking Bamhi. Meanwhile, many older customers browsed leisurely and warmly inquired about Bamhi’s parents, indicating they regularly visited the store.

“It’s not generations of sellers but also generations of buyers – it’s not just one-sided,” Bamhi said, referring to the customers.

In the past six years, since Bamhi took over managing the shop, he has had a front-row seat to the theatrics inside the bookshop. He has met some of India’s biggest writers, witnessed his friend make a marriage proposal inside, attended to a customer who sought certain shades of books to match home interiors, as well as witnessed the changing trends in publishing.

India’s publishing industry is likely to be worth 800 billion rupees (US$9.6 billion) in 2024, compared with 500 billion rupees in 2019, with educational books dominating the market, according to an August 2021 report by professional services firm EY India. But Bamhi said many youngsters have been inclined to buy books after Covid-19 lockdowns, adding that sales have picked up again.

Bamhi said readers are more interested in Urdu poetry and young adult fiction, as well as those written by Japanese and South Korean authors, citing social media as contributing to the popularity of those genres. He added that younger generations are still interested in reading despite digital distractions, which will help bookshops like Faqir Chand continue their legacies.

“People come to our store for the experience – the smell of paper and the touch and feel of the book is irreplaceable,” he said. “They come here to get lost and experience the olden times. The world outside is moving so fast, but when they come in and start browsing, it seems like time has stopped.”

[ad_2]

Source link