In Indonesia, being LGBTQ is viewed as ‘un-Indonesian and a Western import’. Saskia Wieringa wants to change that

[ad_1]

Wieringa’s forthcoming book, due out next year, celebrates her other passion: the history of Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender (LBT) movement in Indonesia.

“It’s an overdue debt that I’m so pleased to be able to repay,” she said.

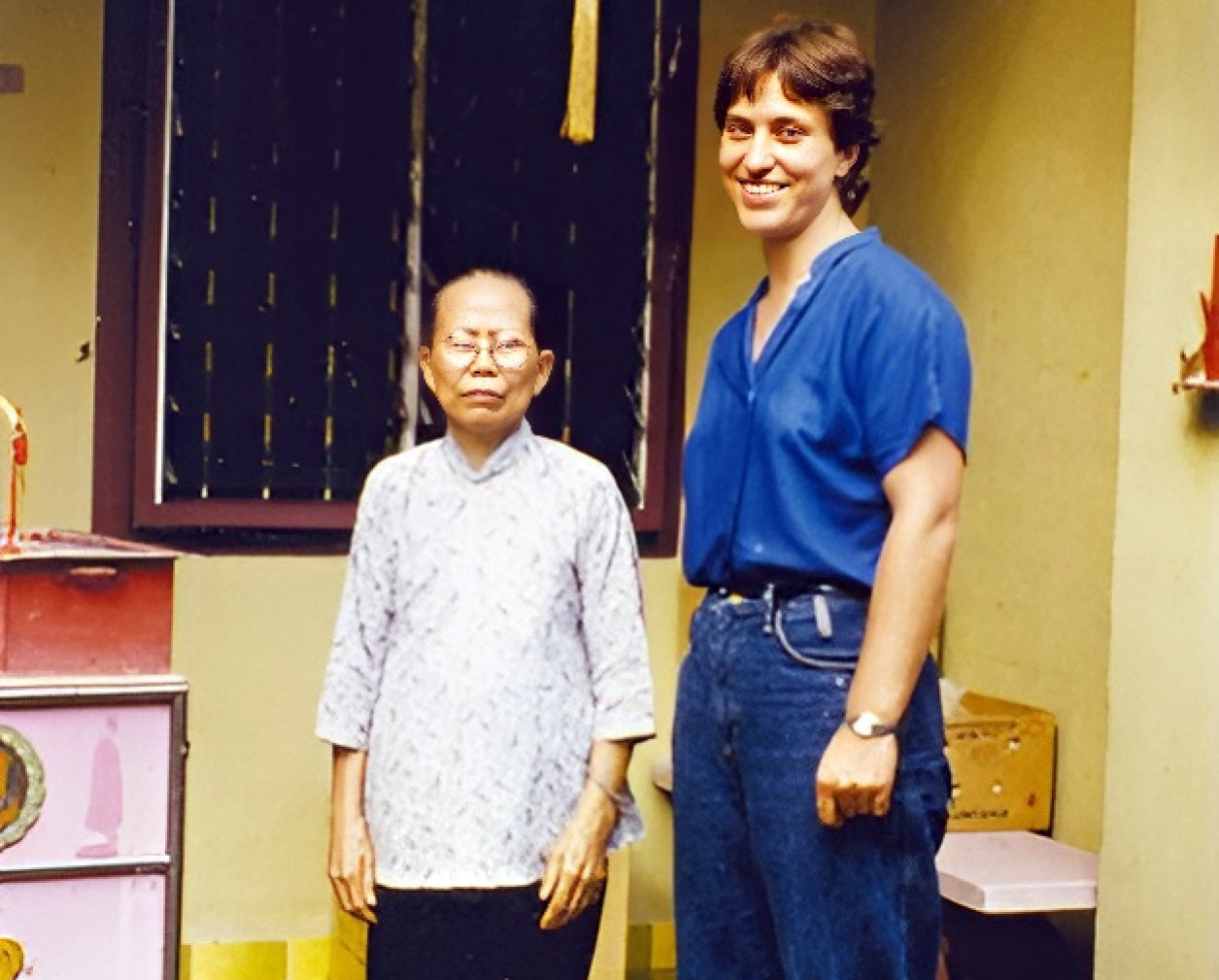

Her involvement with the early LBT movement began in 1981 in Jakarta, when she became a part of Perlesin (Indonesian Lesbian Association), also known as the Menteng Group, the first group of its kind in the country.

During her ban from Indonesia, Wieringa lost touch with Perlesin and did not renew contact until after the collapse of President Suharto’s regime in 1998.

“I caught up with them again in 2001, and they asked me to write their history. They wanted me to restore their dignity and posterity to know their story.”

A central theme in Wieringa’s new book is refuting the prevailing view held by most Indonesians today that the LGBT identity is “un-Indonesian and a Western import”.

In Indonesia, ‘LGBT’ label is linked to criminality amid ‘societal homophobia’

In Indonesia, ‘LGBT’ label is linked to criminality amid ‘societal homophobia’

A 2022 public poll by SMRC found 49.3 per cent of respondents did not think LGBTQ people deserved respect as human beings.

“I’m basing this assertion on historical accounts as well as traditional folklores handed down through the ages.”

Gender fluidity, she claimed, was present in different indigenous societies throughout the Indonesian archipelago, citing the example of the Bissu of South Sulawesi, the most well-known of Indonesia’s gender-diverse traditional groups.

The Bissu are transgender priests of the Bugis ethnic group who, in pre-Islamic era, recognised five different genders.

Apart from the cisgender categories of men and women, there were the calabai, males who dressed as females and calalai, females who dressed as males.

Both calabai and calalai were eligible to become Bissu, a separate priestly class, whose main duty was to mediate with the deities and spirits.

But Wieringa contended other ethnic groups in Indonesia also acknowledged and held sexual otherness in high esteem.

“The Toraja people had their transgender boerake priests – male shamanic healers who dressed and acted like priestesses – while the Ngayu Dayak people of Central Kalimantan had their basir, male-bodied priests who dressed and acted like women.”

MTH Perelaer, a 19th-century Dutch chronicler who spent time in Kalimantan, she noted, had observed with Western disdain typical of the era that many of these basir priests were married to other men.

“But these quintessentially Indonesian indigenous traditions have mostly been lost and forgotten over time. The Bissu, for example, are a dying breed due to modern-day stigma.”

This makes the LGBT community a vulnerable group but it also means more Indonesians are becoming aware of and involved in the public debate on sexual and gender diversity issues

Earlier this year in August, a scheduled monologue by a Bissu priest during an art festival in Bone, South Sulawesi, was banned by local authorities.

“They told us it couldn’t go on because by having a Bissu perform, we were promoting the LGBT agenda,” organiser Bahrudin La Kamaruga said.

Dede Oetomo, founder of GAYa Nusantara, Indonesia’s oldest LGBTQ advocacy group, said similar incidents had occurred sporadically across Indonesia.

“This makes the LGBT community a vulnerable group but it also means more Indonesians are becoming aware of and involved in the public debate on sexual and gender diversity issues,” he said.

But Oetomo said, despite growing challenges, Indonesia’s LGBTQ groups continue their advocacy work, often with the help and solidarity of civil society and pluralism partners. “We still have wonderful allies who would go out on a limb to help us, so not everything is bleak.”

Wieringa said that Western observers should try to see Indonesia from more nuanced perspectives and refrain from trying to impose their own standards.

“Indonesia’s LGBT movement has a different historiography and timeline that don’t fit into the Western model.”

Indonesia’s conservative wrath, scams take centre stage ahead of Coldplay gig

Indonesia’s conservative wrath, scams take centre stage ahead of Coldplay gig

She pointed out that the typical Western fight for LGBTQ rights takes the path of decriminalising homosexual acts, followed by legal reforms leading to marriage equality.

“The Indonesian model doesn’t follow this path and marriage equality is still off the table for any foreseeable future.”

Hartoyo, an LGBTQ activist based in Medan, said the needs of Indonesia’s LGBTQ people are markedly more practical than their counterparts in the West.

“I’m currently advocating for Medan’s elderly transgender people to apply for their [universal healthcare plan] BPJS so that they can access medical services in their twilight years,” he said, adding many had been left without a healthcare plan due to fear of being stigmatised over their gender during the application process.

But Oetomo expressed hope that change for the better was possible.

“I feel the younger generation, especially Gen Z, are becoming more literate and accepting of sexual diversity and ultimately it will be up to them what kind of Indonesia they want to live in.”

[ad_2]

Source link