In Nepal, where feminism is ‘not well perceived’, a library hopes to amplify women’s voices one book at a time

[ad_1]

In the heart of Kathmandu, a small library is aiming to shift mindsets in Nepal – one book at a time.

The library, named Junkiri: The Feminist Library, is shouldering the responsibility of educating girls and women on issues ranging from women’s rights to feminist theories through literature. It is the first of its kind and only such library in Nepal, opened to amplify female voices and become a space supporting feminist ideas, according to Pooja Pant, who started the project.

“We have books for women, by women and about women,” said Pant, a rights activist and documentary filmmaker. “They are extremely progressive in its thoughts and align with feminist theories, which align with equity, equality and breaks stereotypes, and highlight caste and marginalisation that exist in our community.”

Feminism has a long history in Nepal, with women demanding equality for decades.

However, activists said that women’s rights have progressed at a slower pace and largely failed to address issues pertaining to those in the margins.

In the World Economic Forum’s 2023 Global Gender Gap Index, which measures gender parity in economics, education, health and political participation, Nepal slid 20 places to 116 among 146 countries and regions compared with the previous year.

Feminist advocates said educating young girls and women is a crucial step in achieving gender equality, and it was important for them to have access to books outside their school curriculum. But a clear distinction between feminist literature and those written by women has often limited the understanding of feminism.

“Feminism is not well perceived in Nepali society, as it is understood as a movement against men,” writer and editor Anbika Giri said. “We have very limited literature that advocates feminism or women’s perspectives.”

Giri, who has written women-centric books, including one on educating children about sexual abuse, said there is a growing need for spaces like Junkiri to help young people “think, engage and challenge” traditional beliefs.

Junkiri, which translates as fireflies in Nepali, opened its doors in 2020 just before the Covid-19 pandemic and has since attempted to become a guiding light for those searching for feminist literature, according to Pant.

Tucked in an old courtyard in the vicinity of the historic Kathmandu Durbar Square, the library is home to over 2,500 books, including both Nepali and English titles. It has over 500 members and footfall has gradually increased over the years, its librarian Shashikala Khadka said.

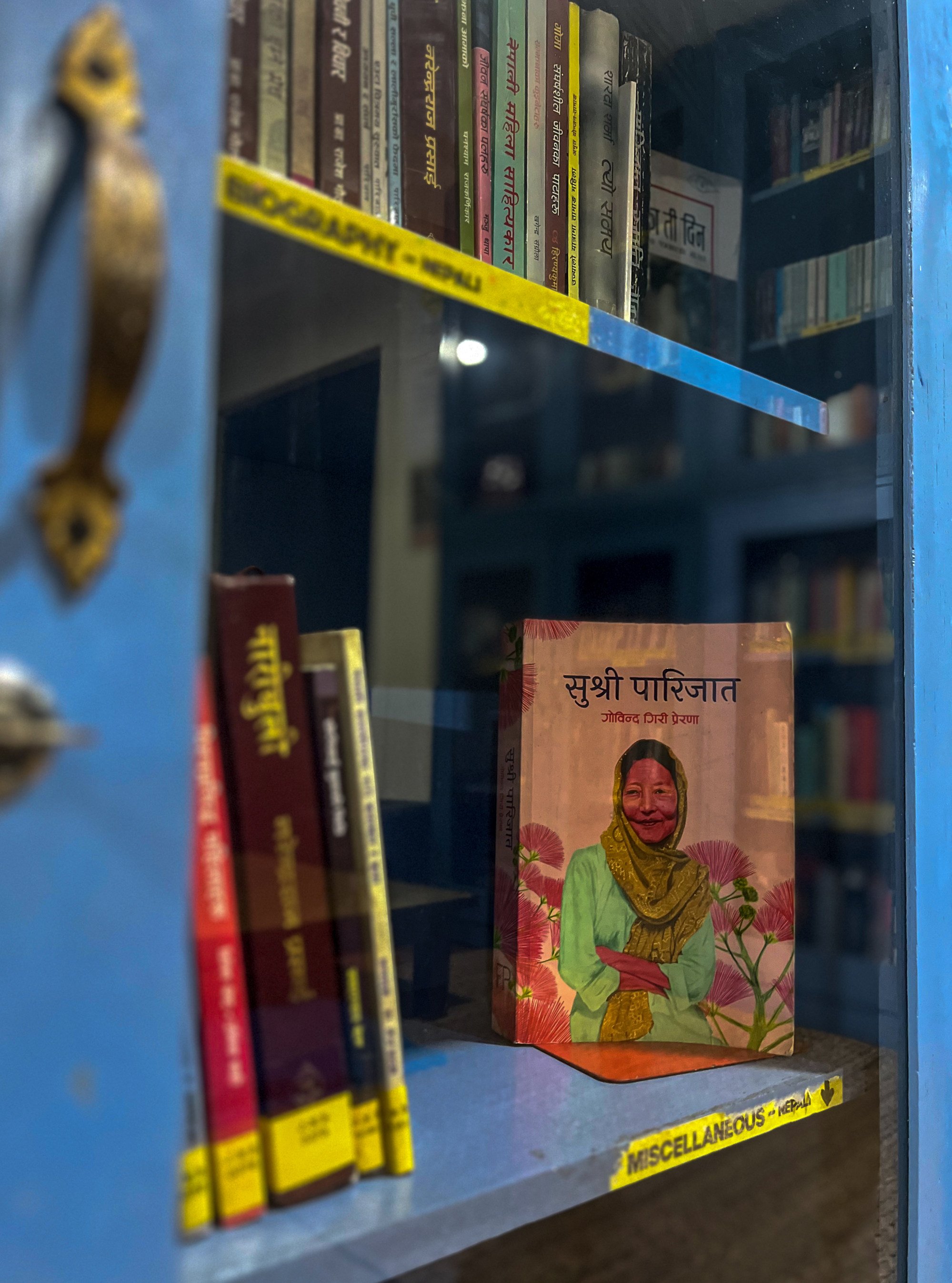

Junkiri now boasts a collection of classic and contemporary authors such as Simone de Beauvoir, Arundhati Roy, Margaret Atwood and Zadie Smith, as well as Nepali writers Parijat and Neelam Karki Niharika.

“Young adults mostly come looking for books they see on TikTok and Instagram,” Khadka said, adding Junkiri also carries popular titles like Alice Oseman’s LGBTQ fiction story Heartstopper. “But it’s a feminist library, so we try to push them to read feminist titles as well.”

Krishtina Bajracharya, a 23-year-old student, said she has been frequenting the library for about five months after she found Junkiri’s profile on Instagram. As she browsed the shelves on a late October afternoon along with her younger sister, she said the books she has borrowed have helped expand her knowledge on feminism.

“We learn about feminism in school, but that’s not enough,” she said. “At first, I thought feminism is only for women, but it’s more about equal rights for everyone.”

Bajracharya has read titles such as Feminism Is … and the Nepali novel Gulabi Umer, and has since encouraged her younger sisters to become Junkiri members.

Though the library initially crowdsourced books, Pant said Junkiri now makes a conscious effort to include titles that are relevant to feminist ideologies, along with few mainstream titles. However, bookstores in Nepal rarely carry an expansive collection of feminist authors, which she blames on the lack of interest and awareness on both sellers and readers, creating a vacuum of women’s voices and stories.

How Yellen’s women’s power lunch exposed China’s divide over women’s rights

How Yellen’s women’s power lunch exposed China’s divide over women’s rights

To fill that void, Pant registered the non-profit she co-founded, Voices of Women Media, in 2015, allowing women to tell their stories themselves in multimedia format. She said Junkiri is an offshoot of that project.

“Women’s stories are always represented in the mainstream media in a sympathetic tone, pitiful tone and they’re always victimised,” Pant said. “We are much more than this. Nepali women isn’t a wholesome group and they are not represented in the stories.”

However, women writers and publications have made a distinct mark in the Nepali publishing scene as early as the 1950s, raising issues that were – and are still – largely considered taboo. Magazines edited by women such as Swaasnimaanche, Pratibha, Jureli and Asmita have tackled issues from sexual violence to abortion.

Meanwhile, writers like Parijat, Prema Shah and Maya Thakuri uninhibitedly wrote about womanhood, sex, and female desires, becoming feminist icons for the next generation of readers and writers.

The books curated at Junkiri attempts to add to those voices in addition to those that promote female role models to girls and titles popular with young adults. However, critics warned the library should be mindful of the books it promotes.

“For a curious and critical mind visiting Junkiri, it should stand out distinctly from other libraries in Nepal that has little bit of every genre of writings to cater to readers of all sorts,” writer Pranika Koyu said. “[Junkiri] is meant for feminist literature, so just aim to be that.”

However, Pant disagreed. She said it was important for the library to “not censor” and make diverse titles available to readers, while not losing sight of the core philosophy of feminism.

“We can have a discussion on those books, discussions on feminist thoughts or the lack of it in these books,” she said. “It starts the conversation.”

Can female genital mutilation ever end if the issue remains taboo to discuss?

Can female genital mutilation ever end if the issue remains taboo to discuss?

Pant said Junkiri has “gone above and beyond the definition of a feminist library” and is now a community library with books that puts feminism at the front. In the coming years, she plans to involve the local government to expand its reach and even open branches outside Kathmandu, where such facilities are almost non-existent.

Meanwhile, writers like Giri and Koyu said spaces like Junkiri will encourage new writers and ideas, while promoting reading culture. Comments left by visitor book at the library entrance share similar emotions.

“Thank you for existing,” wrote one visitor.

“This is a safe space,” said another.

“One needs spaces like Junkiri to learn from each other on feminist values and principles,” Koyu said. “Such spaces can help people comprehend, reflect and have informed but constructive choice on what they want to think feminism is and how it should be practised or talked about.”

[ad_2]

Source link