From October War to ancient treaty: Egypt’s timeless legacy of peace

Egypt’s enduring pursuit of peace is intricately woven into the fabric of its rich and storied past, a narrative that stretches across millennia.

The 51st anniversary of the October War victory serves as a pivotal moment for reflection — an event born out of conflict, yet ultimately leading to a steadfast commitment to lasting harmony, beautifully embodied by the subsequent peace treaty.

Egypt’s dedication to peace transcends modern endeavours, drawing from a wellspring of historical wisdom.

As a celebrated pioneer in the art of peace-making, Egypt’s legacy shines through with the Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty, also known as the Eternal Treaty or the Silver Treaty.

Distinguished as the world’s oldest surviving peace agreement, this landmark document stands as an enduring testament to the enduring promise of peace forged between two ancient civilisations.

These remarkable historical milestones serve to highlight Egypt’s profound influence in shaping a more harmonious world – an influence that continues steadfastly in the present day.

The rich tapestry of Egypt’s history, interwoven with ancient doctrines of peace, resonates through the ages, offering inspiration and fostering unity that echoes through the generations.

This historic treaty was established around 1259 BC between the Egyptian King Ramses II and Hattusili III, the Hittite king.

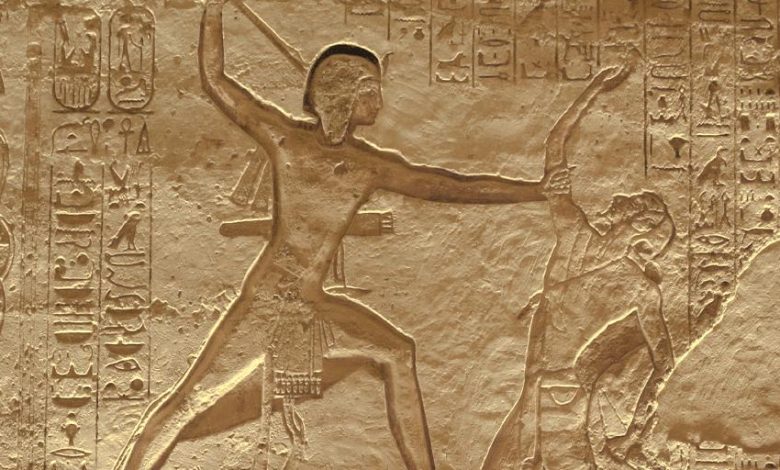

The Egyptian inscriptions of the Battle of Kadesh, now in Syria, have been prominently showcased on the walls of the Abu Simbel Temples since ancient times.

Translations have revealed that these inscriptions were originally etched from silver tablets exchanged by the two parties, though the original tablets have not survived.

The Egyptian account of the treaty was carved in hieroglyphics on the walls of the Karnak temple, complete with descriptions of the figures and seals present on the tablet received from the Hittites.

The Hittite rendition was discovered in their capital of Hattusa, located in present-day Türkiye, and exists on baked clay tablets found within the expansive royal archives.

Two of these tablets are exhibited in the Museum of the Ancient Orient, part of the Istanbul Archaeology Museums, while another is housed in the Berlin State Museums in Germany.

A replica of this treaty is also on display at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City.

The treaty was executed to conclude the prolonged conflict between Egypt and the Hittite Empire, which had engaged in warfare for over two hundred years to gain dominance over the eastern Mediterranean region.

Despite the heavy losses sustained by both sides, neither could claim a conclusive victory in the battle or the overall war. The hostilities carried on indecisively for another 15 years until the treaty’s signing.

Both empires found mutual benefit in pursuing peace. Egypt faced an impending threat from the Sea Peoples, while the Hittites were wary of the growing power of Assyria to the east.

The treaty was officially ratified in the 21st year of Ramses II’s reign and remained effective until the eventual downfall of the Hittite Empire, some eighty years later.

The terms of the treaty included the importance of establishing good relations between the two countries, seeking to spread a peace based on respect for the sovereignty of the two countries, and pledging not to prepare armies to attack the other party.

In addition to establishing an alliance and a joint defensive force, and respecting the envoys between the two countries for the importance of their role in activating foreign policy, resorting to the curse of the gods as a guarantee of this treaty and punishing those who violate it.

Ramses II also tied the knot with Maathorneferure, the daughter of Hattusili III, the Hittite king.

Based on evidence from a papyrus unearthed at Gurob, it is highly probable that she resided in the palace located at Gurob, an archaeological site in Egypt near the Fayoum.

Research into Egypt’s history reveals that it was the first to establish a formal army in 3200 BC. This achievement took place under King Menes’ leadership, who unified Egypt with its northern and southern regions.

Owing to his influence, the Egyptians created the world’s first empire, stretching from Türkiye in the north to Somalia in the south, and reaching from Iraq in the east to Libya in the west.

Historians recognise the Egyptian army as the world’s first structured military force, which evolved through three distinct eras.

During the Old Kingdom era (2700 – 2200 BC), when the pyramids were built, Egyptians were required to enlist for seasonal construction work during the flood days.

Wealthier individuals often paid a fee to avoid this duty. At the time, military armament was basic, comprising batons, sticks with stone tops, and copper-made daggers and bayonets.

In the Middle Kingdom period (2055 BC – 1650 BC), local rulers enjoyed some level of independence, allowing each region to establish its military-like forces.

These forces were organised and equipped comparably to an army, with units dedicated to protecting the king and securing trade, quarry, and mining expeditions. King Senusret III successfully curtailed the power of provincial governors and initiated the development of the first organised national army.

During the New Kingdom era (1550/1544 BC – 1069 BC), Egypt’s military strategy shifted from a defensive stance to one focused on offence and incursion.

This change aimed to establish strategic depth within neighbouring nations and safeguard Egypt’s borders by targeting countries that might pose a threat of occupation.

This strategy underpinned the development of what is considered the world’s first trained regular army.