Kazakhstan Surpasses Global Average in Economic Gender Equality Metrics, Says World Bank

ASTANA – Kazakhstan outperforms the global average in legal and supportive frameworks and expert opinion criteria on enabling women’s economic opportunity in the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law (WBL) 2.0 report, which was presented to local policymakers and government representatives on Oct. 1 in Astana.

Closing the gender gap between the number of working men and women could help raise Eastern Europe and Central Asian gross domestic product (GDP) by $1.1 trillion, the International Labour Organization (ILO) report says. Photo credit: freepik.com

In its annual report, the World Bank analyzes the legal reforms concerning women’s economic opportunities and working rights in 190 countries worldwide, including Kazakhstan, which is among 23 countries from Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

The report has three pillars: legal frameworks that enforce and monitor non-discrimination on the basis of sex; supportive frameworks, which measure policy mechanisms to implement those laws; and expert opinions, which shed light on experts’ perceptions of women’s outcomes.

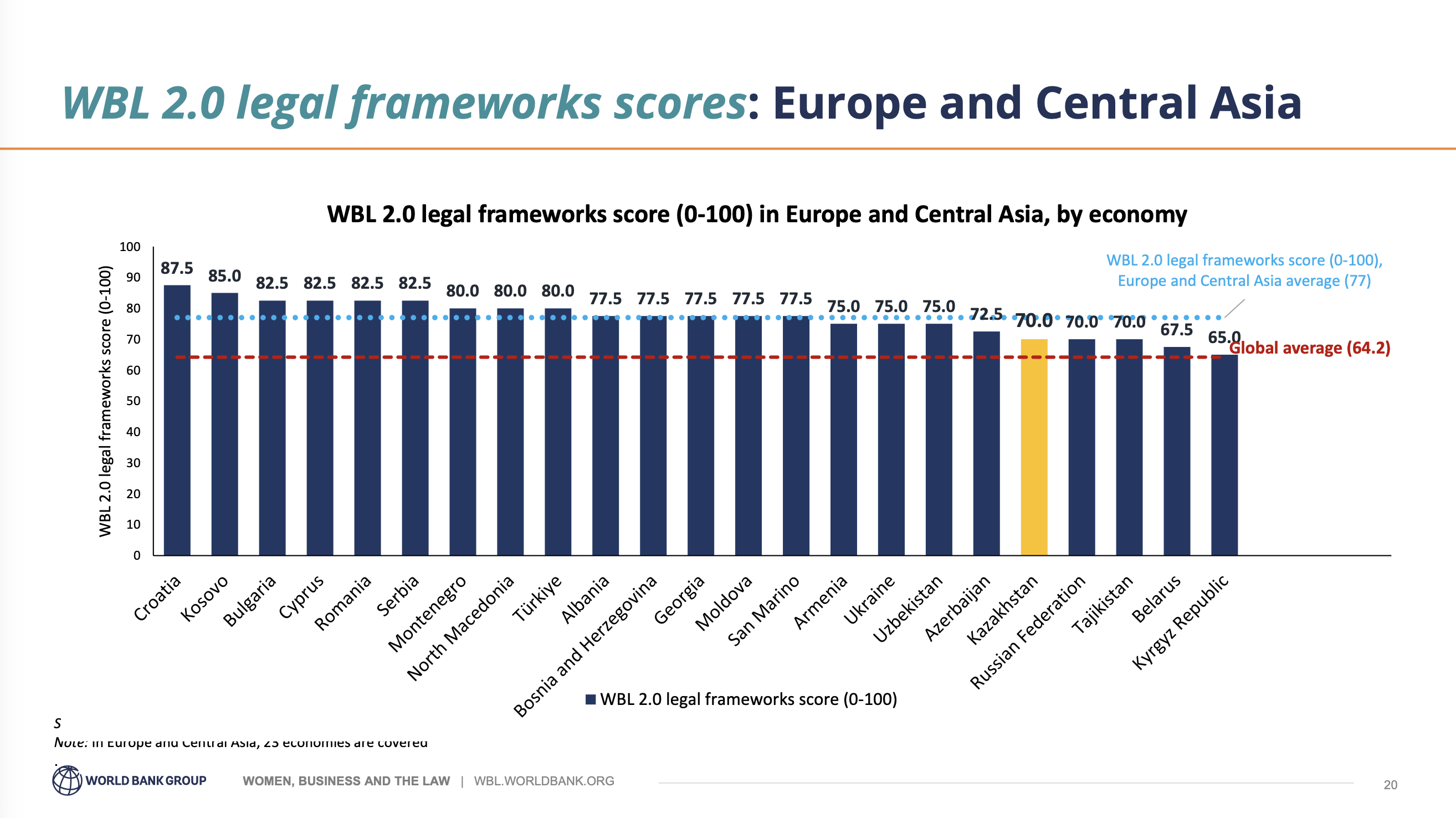

Despite scoring above the global average in legal frameworks, Kazakhstan ranks among the bottom five countries in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia region, with a score of 70. Source: presentation on World Bank’s WBL 2.0 report

For the first time, the new WBL 2.0 report also considers the impact of affordable and quality childcare and women’s safety issues, as they both affect women’s ability to work.

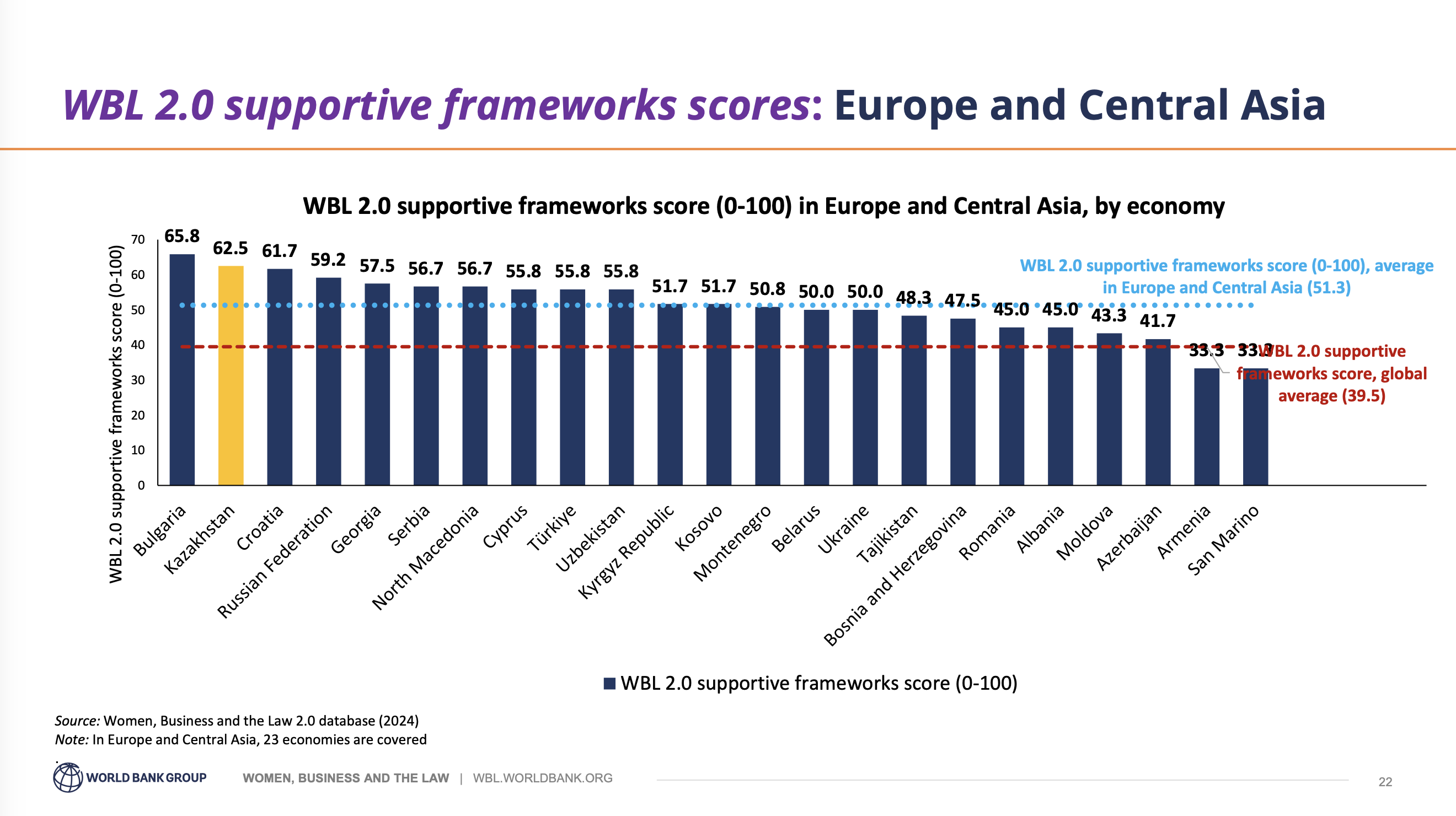

“All in all, on the three measures, including legal frameworks, supportive frameworks and expert opinions, the Eastern Europe and Central Asia regions score considerably higher than the world average,” said Alena Sakhonchik, private sector development specialist at the World Bank group’s WBL project.

“Kazakhstan scores higher than the global average on all three measures, and higher than the Eastern Europe and Central Asia average when it comes to the supportive frameworks and expert opinions, but falls short on the legal frameworks, with a score of 70 out of 100. It indicated that quite a bit of room for improvement exists despite the progress that has been made so far,” she said.

Kazakhstan ranks second in supportive frameworks, scoring 62.5 out of 100, compared to the regional average of 51.3. Source: presentation on World Bank’s WBL 2.0 report

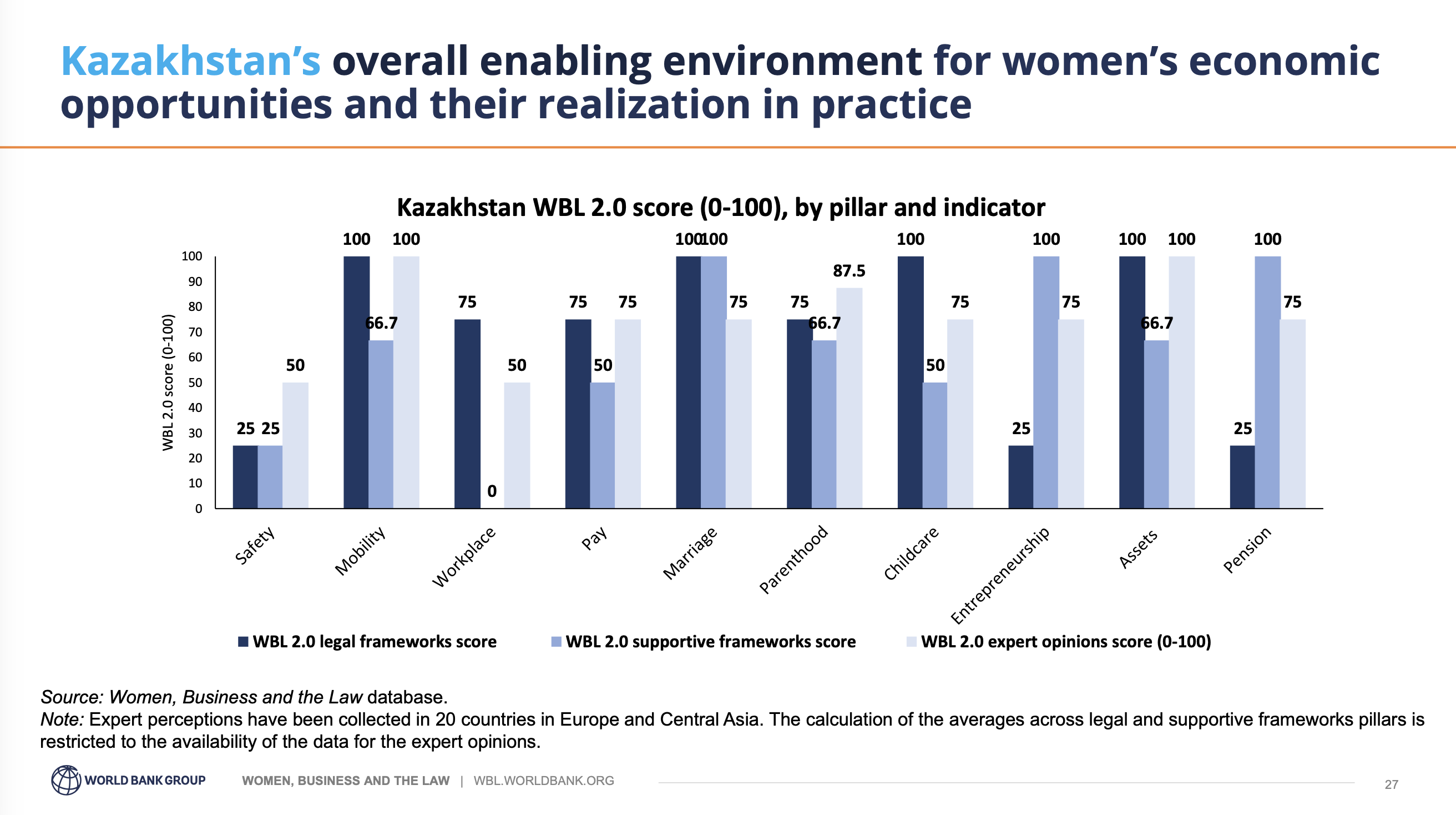

Kazakhstan received a perfect legal score on four legal indicators: mobility, which examines constraints on women’s freedom of movement; marriage, which assesses legal constraints related to marriage and divorce; affordable childcare; and assets, which analyzes gender differences in property and inheritance law.

The country also ranks second in supportive frameworks, scoring 62.5 out of 100, compared to the regional average of 51.3 for Eastern Europe and Central Asia. In Kazakhstan, such frameworks are particularly strong in marriage, entrepreneurship and pension indicators.

Women’s safety

Despite strong scores in certain areas, Kazakhstan needs to improve in certain aspects to fully enhance women’s economic opportunities. Women’s safety is where Kazakhstan lags the most. The nation’s score is just 25 in legal and supportive frameworks. Although the law addresses domestic violence, further legal protection is required against child marriage, sexual harassment, and femicide.

Women’s safety is the criterion where Kazakhstan lags the most across all three pillars, while it scores the strongest in marriage rights. Source: presentation on World Bank’s WBL 2.0 report

“When we look at child marriage, we see that the reason why Kazakhstan doesn’t get a full score is because there are no law enforcement measures or sanctions for anyone who authorizes or who’s involved in the marriage of girls and boys in violation of the age requirements,” said Isabel Santagostino Recavarren, private sector development specialist with the WBL project.

“Moving on to the sexual harassment question, to be able to get the score, the law must address at minimum two of the four forms of sexual harassment that includes sexual harrassment in employment, in education, in public spaces and in cyberspace. And we see that there is no legislation addressing any of the four in forms of sexual harassment in Kazakhstan,” she said.

Women in entrepreneurship

Women in Kazakhstan also face some obstacles in entrepreneurship.

“This is for three reasons. First of all, the absence of a non-discrimination clause based on gender in access to credit. This provision would be important because its presence has been linked to higher ability to access loans and also to have a bank account and a debit card. Also we see the absence of gender quotas on corporate boards. This is an important tool which has been found to increase the percentage of female leaders. The third is the absence of gender sensitive procurement provisions for public procurement processes,” said Recavarren.

According to Diego Ubfal, senior economist in the World Bank’s gender group, this is more about the amount of financing rather than its availability.

“Even though index data shows that women are not less likely to get loans here in Kazakhstan than male-led firms, the question is the size of these loans. In many cases, the low segment and the very high segments are covered but women in middle-sized firms have difficulty in getting larger loans. Particularly because of lack of collateral. Many women don’t own homes, houses or any collateral that they can show to the banks,” said Ubfal.

The good news is that Kazakhstan meets all the criteria for supportive frameworks in entrepreneurship. Sex-disaggregated data on business activities, entrepreneurship, and women-owned businesses is published in Kazakhstan. Government-led programs also provide support to female entrepreneurs regarding access to finance or agency and empowerment. The national government plan also focuses on women’s access to financial services.

The gap between the laws and the frameworks supporting their implementation continues to persist across other areas, the largest being the workplace indicator that analyzes laws affecting women’s decisions to enter and remain in the labor force, and in childcare.

The implementation gap underpins the hard work that lies ahead, even though Kazakhstan has instituted equal-opportunity laws across many sectors.

Global gender outlook and the World Bank’s vision

Closing the gender gap between the number of working men and women could help raise Eastern Europe and Central Asian gross domestic product (GDP) by $1.1 trillion, which is equivalent to 23% of annual regional GDP, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO) report.

Hana Brixi, the World Bank’s global director for gender, during the presentation. Photo credit: the World Bank’s office in Kazakhstan

Hana Brixi, the World Bank’s global director for gender, highlighted the institution’s role in supporting gender equality.

“We are in a historic moment for the World Bank group, when it comes to gender equality. This is the first time ever that the World Bank has such a high ambition to help countries accelerate gender equality and it is not only commitment based on what is the fair thing to do, but it’s also based on evidence. By now, the evidence is very, very clear that advancing gender equality is the smart thing to do for countries,” said Brixi.

She argues that investing in women is an economically sound strategy. At the global level, the long run income per capita in countries would be 20% higher if women were employed at the same rate as men.

“We also have evidence that when women participate in decision making the outcomes are better. It’s the resilience in households, better resilience in communities, stronger investment in the human capital of children – so in nutrition, education and health of children. We also see higher profitability in companies, when there is more gender balance in decision making,” said Brixi.

“We also see, for example, in disaster risk management, that when women participate in decision making the disaster risk management plans are better quality, and their implementation is also more successful in terms of covering the needs across the communities. So a strong case to be made for women’s participation in decision making and women’s leadership,” she said.

The World Bank prioritizes ending all types of gender-based violence, expanding women’s economic participation and engaging women as leaders.