Kazakh Playwright Brings Mankurt Legend to French Stage

ASTANA – Kazakh playwright Inkar Karimova has brought the ancient legend of the mankurt, a memory-deprived slave, to a French audience. The play “Mankurt” debuted at the Théâtre de l’Ouvre-Boîte in Aix-en-Provence, France, on Sept. 13-14, and was subsequently staged at Marseille’s Théâtre des Chartreux on Sept. 20-22.

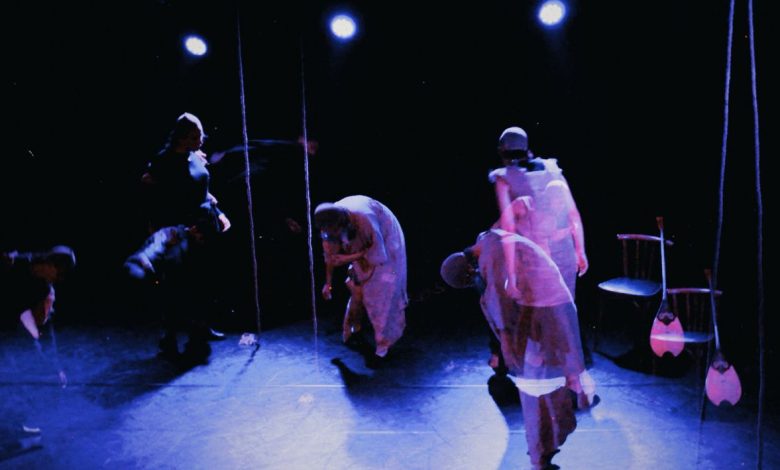

A mankurt is a war prisoner transformed into a memory-deprived slave from the Kyrgyz writer Chinghiz Aitmatov’s novel. Photo provided by Karimova.

Karimova, a graduate student at Aix-Marseille University in France, developed the play as part of her Master’s project.

“I started writing the play when I arrived here. We were asked to choose a theme to work on, and because I already had an idea related to my culture—specifically, my admiration for Chinghiz Aitmatov—I remembered the legend of the mankurt,” said Karimova.

The play is inspired by Kyrgyz writer Chinghiz Aitmatov’s novel “The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years,” particularly the story of a mankurt, a war prisoner transformed into a memory-deprived slave. In the legend, his mother, Naiman-ana, is tragically killed by her mankurt son when she attempts to rescue him.

A personal take on mankurt’s story

Following Aitmatov’s novel, the term “mankurt” has become a reference for individuals who have lost connection to their ethnic roots and forgotten their heritage, culture and language. This meaning persists in the Kazakh and Kyrgyz languages.

The play attempts to show how centralized, hierarchical system of the Soviet Union brought a lasting impact on people’s ways of thinking. Photo provided by Karimova.

In Karimova’s “Mankurt,” however, she brings out her personal story, connecting it to her own experiences.

“I thought I’d like to write the story myself rather than simply using something already written and passing it on to a French audience. For them, retelling an existing story wouldn’t carry any personal weight. I wanted to reach their minds, their souls, because for them, what is happening in Kazakhstan, in Central Asia, is completely unfamiliar and incomprehensible,” said Karimova.

The play marked her debut both as a director and as an actress.

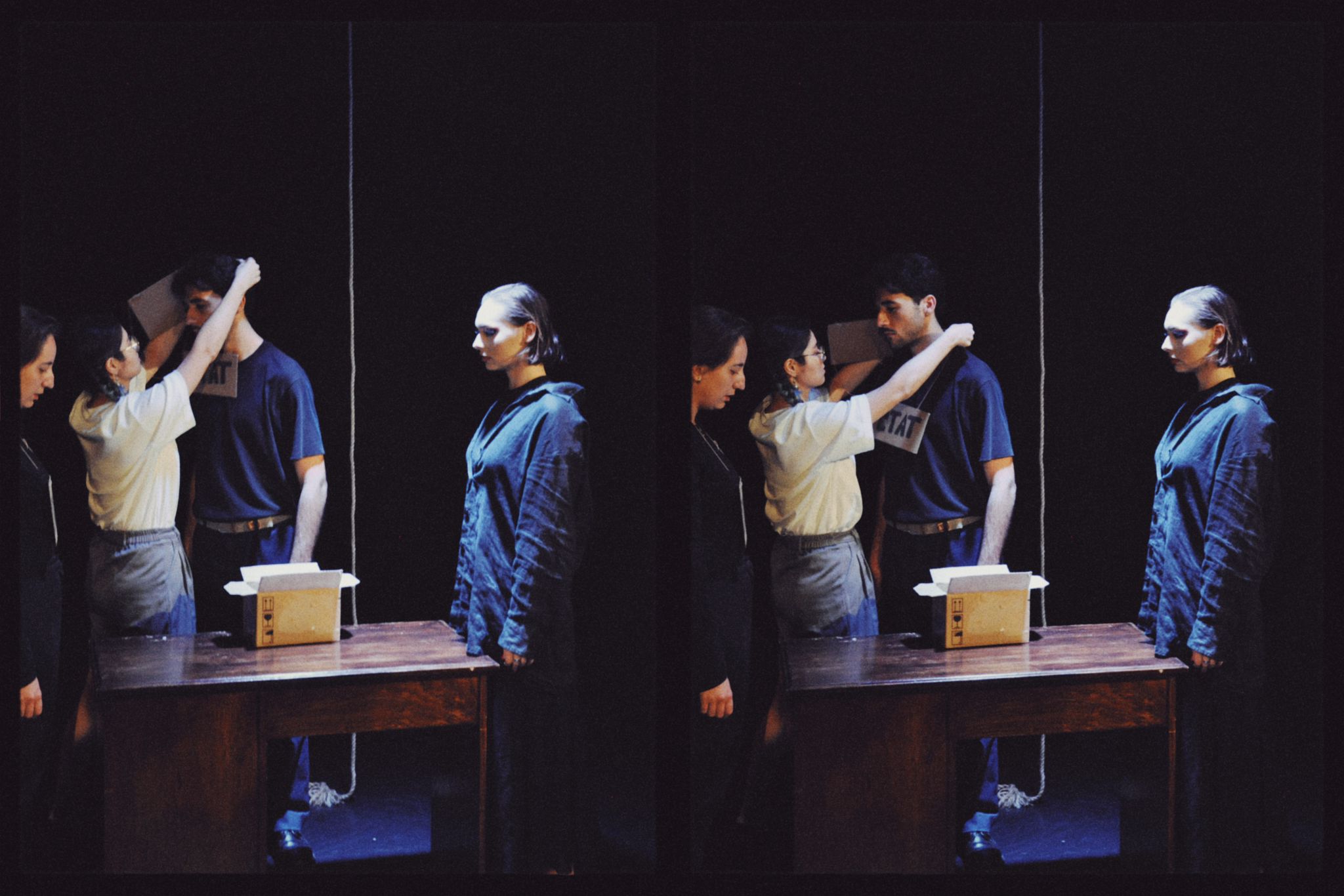

Following Aitmatov’s novel, the term “mankurt” became a reference for individuals who had lost connection to their ethnic roots. Photo provided by Karimova.

“In the first year of working on the play, other actors and actresses were telling the story of the mankurt, the repressions, and Kazakhstan. But it felt somewhat disconnected—like having an African woman or a Frenchman narrating the story. Then, my mentor suggested, ‘Why don’t you perform it yourself?’ Until that moment, I had never considered it. I thought the director’s role was only to direct while the actors performed,” said Karimova.

“Who better to tell this story than you? It’s your story,’ my mentor said. So, in the second year, I began rewriting the play. I edited everything to suit myself and added my monologues,” she added.

By playing herself, Karimova was able to bring more texture and depth to her work.

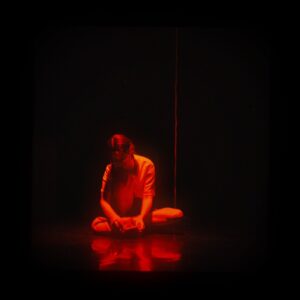

“I’m playing myself, telling my own story as Inkar. I share personal experiences, how the echoes of the Soviet Union and colonization, although they happened in the last century, still resonate today, at least in my own life,” she said.

The centralized, hierarchical system of the Soviet Union brought a lasting impact on people’s ways of thinking that endures across generations even today.

“I draw parallels between the country’s attitude toward its people and my personal relationships—whether with my teachers, parents or in romantic situations. It mirrors the top-down system and how hierarchy operates. People struggle to express their opinions, emotions, and feelings because they’ve been conditioned to keep everything hidden. You always had to hold it all inside, to stay silent, and keep personal matters within the home, never to share openly,” said Karimova.

Audience interaction

For some, the play might serve as a wake-up call; for others, it is an introduction to significant events in the country’s past, such as Stalinist repression, famine and the nuclear tests at the Semipalatinsk polygon.

“Many people received it very positively. There were a lot of good comments, and many people were deeply moved. There were even people who cried during the scene of my monologue about the Semipalatinsk polygon,” said Karimova on the initial impressions of the audience.

In the play Karimova plays herself. Photo provided by Karimova.

In “Mankurt,” she strives to build conversations with audiences, creating dynamics that take them out of their comfort zones.

“There’s a scene where we speak different languages. During the first week it was me, an Armenian and a Latvian – all these different languages intertwined and each of us sharing what we have accumulated. The audience perceives this scene very differently: for some, it’s uncomfortable because they don’t understand. I included this scene intentionally to put people in a state where they are, well, annoyed by the fact that they don’t understand. Given that in France, everybody speaks French, and you can’t even say something in English because you’ll be answered in French, it’s very rare for them to be in that state. So it was kind of interesting to show them, let’s say, ‘here, look what it was like for us,’” said Karimova.

“Another layer to that [scene] is that the language we speak doesn’t really matter—it’s already clear what we want to convey, and they understand. Occasionally, we use a few phrases in French before switching back to our native languages. As if we experience brief enlightenment before reverting again,” she added.

The play is unique not just in terms of its content but also in terms of form. In attempts to experiment, Karimova pushes the barriers between audience and performers, breaking the fourth wall and encouraging interaction.

“Everyone always notes that they liked the beginning because it starts with a standup. I come out and start talking to the audience, and throughout the performance, I continue interacting with them from time to time,” said Karimova.

In some instances, the audience is really taken by surprise.

“At certain moments, if someone sneezes, for example, I can interrupt my monologue and say ‘bless you,’ and then continue. Or in other instances, if someone is leaving the auditorium, I might remark, ‘Geez, you’re leaving already? Well, thanks for coming. We’ll carry on without you.’ This often shocks the audience, but at the same time, they feel good because I’m acknowledging them and they become part of the play,” she said.

Karimova is now in discussions with several other theaters in France about bringing her play to more stages.