Malaysia’s ‘China plus one’ gold rush stumbles over a US tariff threat

On May 15, US authorities launched an anti-dumping investigation into solar panel exports from the four, responding to a petition from the American Alliance for Solar Manufacturing Trade Committee. A two-year exemption from anti-dumping scrutiny the countries had previously enjoyed expired on June 6.

Just weeks later, Benny’s employer – one of the world’s largest solar module suppliers – laid him off as part of a broader downsizing. Jinko Solar has not commented on the closure of its Penang facility after nine years. Yet in a June interview, Li Zhenguo, founder of rival Longi, which operates in Malaysia’s Selangor, voiced concerns about the industry’s future amid a “clearly determined” US strategy to safeguard its solar market. “The question is if we should shut down factories in Southeast Asia or keep them as a backup,” he said, as reported by the Beijing-based Green Energy Daily.

US tariffs could soar as high as 270 per cent after the investigation wraps up, potentially obliterating the competitive edge that Southeast Asian manufacturing once enjoyed, warns Huaiyan Sun, a senior consultant on solar supply chains at global energy transition consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

But for now, Southeast Asia remains a hotspot, buoyed by its abundant supply of chips that are crucial for solar technology.

Tariff turmoil

“For anything on national security … the US has shown it will not hesitate to take strict, appropriate action” to protect its interests, warned Wong Siew Hai, president of the Malaysian Semiconductor Industry Association (MSIA).

Data from the International Energy Agency reveals that over 80 per cent of global solar module production is concentrated in China, home to the world’s top 10 manufacturers. Chinese solar producers have heavily invested in Southeast Asia, which supplied about 10 per cent of global solar demand in 2023, according to the Asian Development Bank.

What we are seeing right now are efforts to reshore manufacturing to the US

The US embassy in Malaysia did not immediately respond to a request for comment, and Malaysia’s Ministry of Trade and Investment declined to answer questions for this article.

Experts agree that Southeast Asian solar supply chains are now under intense scrutiny. “What we are seeing right now are efforts to reshore manufacturing to the US,” said Cheah Wen Chong, an Asia research analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit.

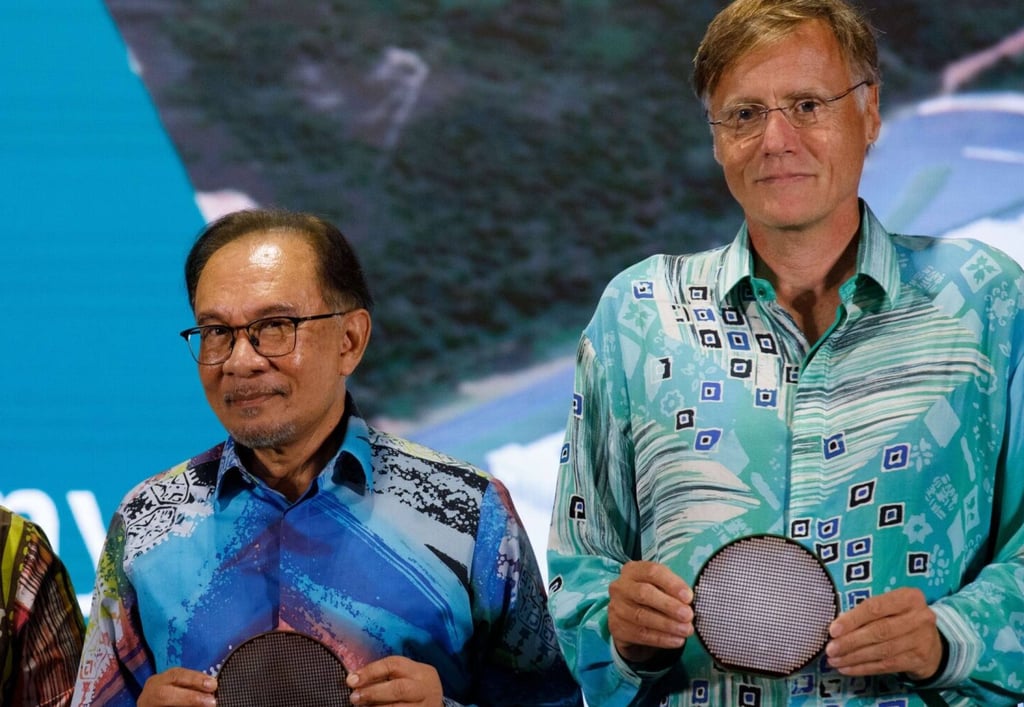

Malaysia, with its decades of tech experience, English-speaking workforce and strategic port access, had the advantage. Coupled with tax incentives and a welcoming government, the country positioned itself as a prime destination for tech investments.

Chip makers are “all about derisking”, said MSIA’s Wong – particularly in light of global conflicts and climate-related disruptions that have strained supply chains.

The interest among investors remains strong and “is still increasing”, because Malaysia is seen as a conducive environment. “We have 50 years of experience in the semiconductor industry with a strong ecosystem and talent available, and a business friendly government,” he said.

Chinese companies are also eyeing Malaysia with growing interest. In April, three Chinese firms unveiled plans to invest US$100 million in Penang, which has been dubbed the “Silicon Valley of the East”. Their goal: to establish bases for semiconductor packaging, materials, and equipment manufacturing, alongside producing etching and film-processing tools essential for wafer fabrication.

Yet, analysts caution that Malaysia must tread carefully between Western and Chinese interests amid ongoing US sanctions and tariff escalations targeting China. “There is definitely some concern,” said Shazwan Mustafa Kamal, a director at Vriens & Partners, a government risk consultancy. “If Malaysia faces tariff hikes on solar panel exports, those could be extended to include other sectors down the line as well.”

The evolving tariff landscape presents a complex challenge for countries like Malaysia. Last year, the US emerged as the Southeast Asian nation’s third-largest investment partner, pumping in US$4.7 billion across 62 approved projects, according to the Malaysian Investment Development Agency. China followed closely behind, contributing US$3.2 billion through 122 projects.

If Malaysia were to become overly reliant on China … it could be flagged as a potential risk to US national security

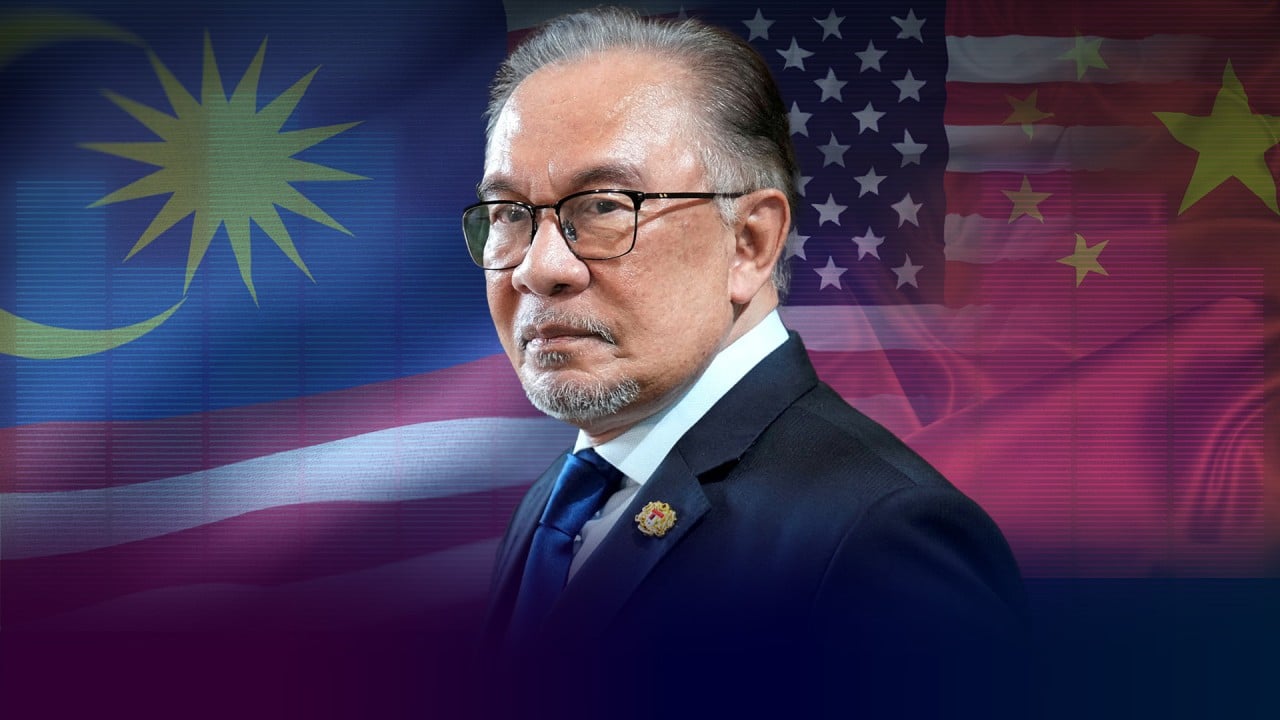

Malaysia’s stance of geopolitical neutrality is crucial for avoiding the brunt of US sanctions, experts say. But maintaining this balance means ensuring the country isn’t perceived as a launch pad for Chinese access to high-end chips and technologies banned by Washington, such as Nvidia’s advanced processors and AI-modelling chips.

“If Malaysia were to become overly reliant on China in this sector, it could be flagged as a potential risk to US national security,” warned Doris Liew, an economist at the Institute of Democracy and Economic Affairs in Kuala Lumpur.

Stars and gripes

For some Malaysia watchers, Anwar’s overtures to China and Brics reflect a prime minister leveraging new-found political stability and the region’s economic potential to enhance his country’s standing. “Concerns that Malaysia’s recent foreign policy posturing under PMX is leaning heavily towards China are hyped up,” said Deborah Chow, an associate director with political risk consultancy BowerGroupAsia, using a popular term to refer to Anwar, Malaysia’s 10th prime minister.

Experts argue that the notion of commanding unwavering loyalty from Southeast Asian nations is outdated, especially as the region’s economy grows and millions of new consumers emerge for markets ranging from smartphones to electric vehicles.

Southeast Asia took time to regain its footing after Trump ripped up trade rules that had threaded together supply chains reliant on cheap labour and manufacturing throughout the region. Since then, countries have explored a range of economic alternatives.

Malaysia has agreed bilateral agreements with China and India to conduct trade using their own currencies, aiming to mitigate exposure to foreign exchange volatility. “Anwar sees de-dollarisation as a more stable trading system” than relying on the US currency, risk consultant Shazwan said. “Especially during the ever-present US-China trade wars” that began in 2016.

This foreign policy shift has also broadened Malaysia’s semiconductor horizons, paving the way for collaborations with nations eager to tap into the booming global market for chips.

“China has a lot of interest in Malaysia because we have the best [semiconductor] ecosystem, we have the experience and the culture, food and living conditions are quite familiar to them,” MSIA’s Wong said.

With revenue from the global semiconductor sector projected to soar from US$577 billion in 2022 to US$1 trillion by 2030, “everyone is asking, ‘why can’t my country get a piece of the cake?’”