Japan’s police to deploy AI-powered drones in disaster-hit areas to deter looters

But the technology would place “great power” in the hands of the police that some claim could be abused, Ishizuka said.

“A key part of the police’s job is to prevent crime and that includes ensuring the security of an area that has been affected by a natural disaster,” he told This Week in Asia.

“Drones would make that much easier to do and reassure people who have had to evacuate their homes that they are being protected. In that respect, this is not such a radical proposal and it is needed because of recent disasters,” he added.

The March 2011 earthquake and tsunami that devastated north-east Japan and killed more than 20,000 people and its aftermath was still relatively fresh in many people’s minds, Ishizuka said.

Millions of Japanese have also been unnerved this month by warnings that the long-feared megathrust earthquake in the Nankai Trough, off southern Japan, is imminent.

There were a few reports of looting in the aftermath of the 2011 quake but far more cases were reported after the 7.5-magnitude Noto peninsula tremor on January 1.

Ten days after the Noto disaster, in which 339 people died, “looters, scam artists and thieves have descended on Ishikawa Prefecture, preying on victims of the New Year’s Day earthquake”, the Asahi newspaper reported.

Police confirmed 17 cases of burglary and theft, including cash and personal belongings from a “ryokan” inn that had been evacuated while companies offered to carry out repair work for exorbitant fees.

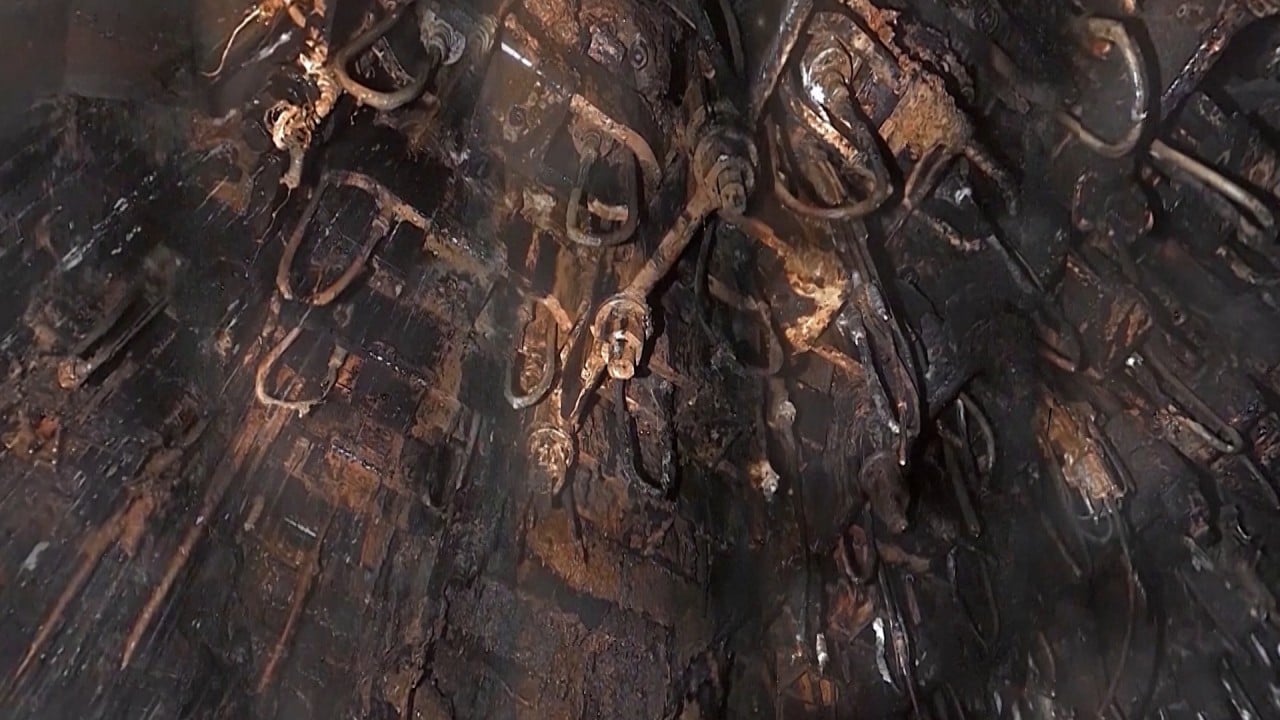

Many homes had been so badly damaged that it was impossible to lock or close some doors, while residents had been instructed to leave because the structures were unsafe, according to the police.

In the aftermath of the disaster, police stepped up patrols and worked with neighbourhood watch groups to protect communities but monitoring the entire area proved impossible.

“Public concern has been heightened because of the recent Nankai Trough earthquake alerts and it is natural for the government and the police to look for ways to control people at a time of confusion such as after a natural disaster,” said Ishizuka, who was previously director of the criminology research centre at Kyoto’s Ryukoku University.

“On the other hand, this sort of technology can be abused,” he said, pointing out the potentially “horrific” possibilities of the police being given too much power in the aftermath of a disaster.

After the devastating 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, which registered magnitude 7.9 in Tokyo and Yokohama and caused around 140,000 deaths, the Japanese military, police and vigilante groups killed an estimated 6,000 Korean and Chinese residents. Without evidence, the victims were accused of looting from Japanese homes and poisoning wells.

“I expect that there will be strong resistance from some areas that using AI to track people’s movements is a breach of their human rights,” Ishizuka said.