China or India? Sri Lanka’s presidential election becomes a battleground for influence

Sajith Premadasa, who split from the UNP in 2019, will represent Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), while Anura Kumara Dissanayake of National People’s Power (NPP), and leftist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) are also candidates.

Analysts say the outcome of the polls could shift the country’s delicate geopolitical balancing act between its two regional powerhouse neighbours – especially if the NPP’s Dissanayake wins a majority.

Yet Wickremesinghe’s pro-India leanings are unmistakable. He has touted plans for currency integration with the Indian rupee and welcomed high-profile Indian investments, like those from the Adani conglomerate, which is thought to have close ties to Modi’s government. This has drawn vocal resistance from the opposition led by Premadasa.

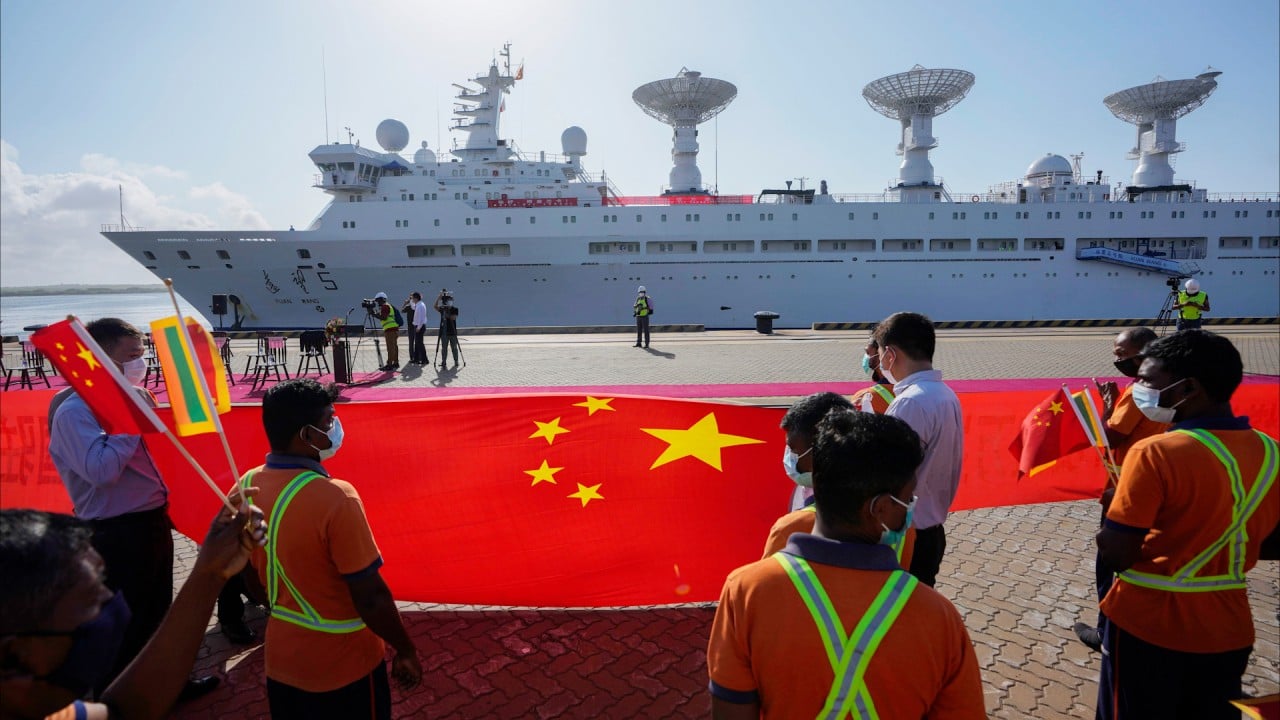

India has a long and complex history of working with both the incumbent Wickremesinghe and the previously dominant Rajapaksa clan. Yet amid this tangled web of relations, one thing is clear: whichever candidate emerges victorious, China will be eager to engage. The “bilateral relationship is entrenched”, Samaranayake said – Beijing has made deep inroads in Sri Lanka, and it’s unlikely to let a change in leadership disrupt its strategic foothold.

The potential rise of the NPP, however, has Delhi on edge. Its fiercely anti-India platform and its close ties to China are seen as a major thorn in the side for India, according to Harindra B Dassanayake, an analyst at Muragala Centre for Progressive Politics and Policy in Sri Lanka.

“India will be compelled to be cautious with a potential NPP leadership, while China will see it as an opportunity to increase their presence in the region,” he said.

Samaranayake echoed this sentiment, noting that the NPP would represent “a new and uncertain dynamic for India to manage in its external relations”.

“This reflects the asymmetry of power for a smaller state, navigating the dominant country in its region,” she said. “If the NPP wins, this will be a new development in Sri Lanka’s history that observers will need to track for potential shifts in the country’s external approach.”

Meanwhile, a continuation of the status quo under either Wickremesinghe or Premadasa would likely mean business as usual for both China and India, Dassanayake said. However, he noted that the spectre of a “potentially weak political legitimacy” for the incoming president could “open a new avenue for increased pressure from geopolitical actors”.

Colombo has long viewed its foreign policy through an economic prism, rather than ideological allegiances, Devapriya said – though there is broad recognition that Sri Lanka now needs to be both “non-aligned” and “multi-aligned”.

“Multi-aligned in terms of trying to gain economic leverage by being as friendly as possible with everyone,” he said. “Non-aligned in terms of not being involved or privy to any of the big power plays and power conflicts and tensions that we are seeing right now.”