Behind Steppes: What Does It Take to Protect Biodiversity in Kazakhstan

ASTANA – Protecting the biodiversity of a country as huge as Kazakhstan is not an easy task. For Vera Voronova, an executive director of the Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity of Kazakhstan (ACBK), this task became a life mission. Voronova spoke to The Astana Times, sharing what inspired her to take on such a career, the strategic goals of the association, and why it can be challenging to ensure biodiversity protection in Kazakhstan.

A deep connection to nature is what Vera Voronova developed since early childhood. Photo credit: Voronova’s personal archive

Steppe – there’s nothing like it

Voronova’s passion and care about nature are evident from the first meeting. She grew up in a rural area in central Kazakhstan, which explains her deep connection to nature, particularly the vast Kazakh steppes.

“I suppose that is why I am such a huge fan of the steppes and why I feel like an ambassador for it. I always tell people that, sure, cities are great, forests are great, but the steppe—there’s nothing like it. Especially in spring, when you arrive and breathe in the fresh scent of grass, wormwood, and the songs of skylarks. That open space, where nothing threatens you, and you can see everything—it gives me a profound sense of personal comfort,” said Voronova.

She said her father nurtured this connection to nature by loving fishing, mushroom picking, and spending time outdoors.

“While I can admire other natural landscapes and enjoy being in different environments, the steppe is the only place where I truly feel at ease,” she said. “We would often spend entire weekends in nature, leaving early in the morning and returning late at night, sometimes even staying overnight. From a young age, I loved everything about these trips, feeling comfortable and at home, even without the usual amenities.”

Her family supported her choice to study ecology at a university. While a student, she also participated in the Conservation Leadership Program, which has been a pivotal moment in her journey.

This is a partnership of three of the world’s leading biodiversity conservation organizations. Voronova said she would “wholeheartedly recommend” it to aspiring conservationists.

As her project for this program, Voronova chose to research the death of birds, particularly birds of prey, at power lines. Photo credit: Voronova’s personal archive

Strategic areas of the association’s work

Founded in 2004, the ACBK’s mission is to preserve Kazakhstan’s unique biodiversity through research, collaboration, public engagement, and education.

Voronova said one of the association’s key projects is the Altyn Dala (Golden Steppe) program, which focuses on the study, restoration, and conservation of Kazakhstan’s steppe ecosystems and their flagship species.

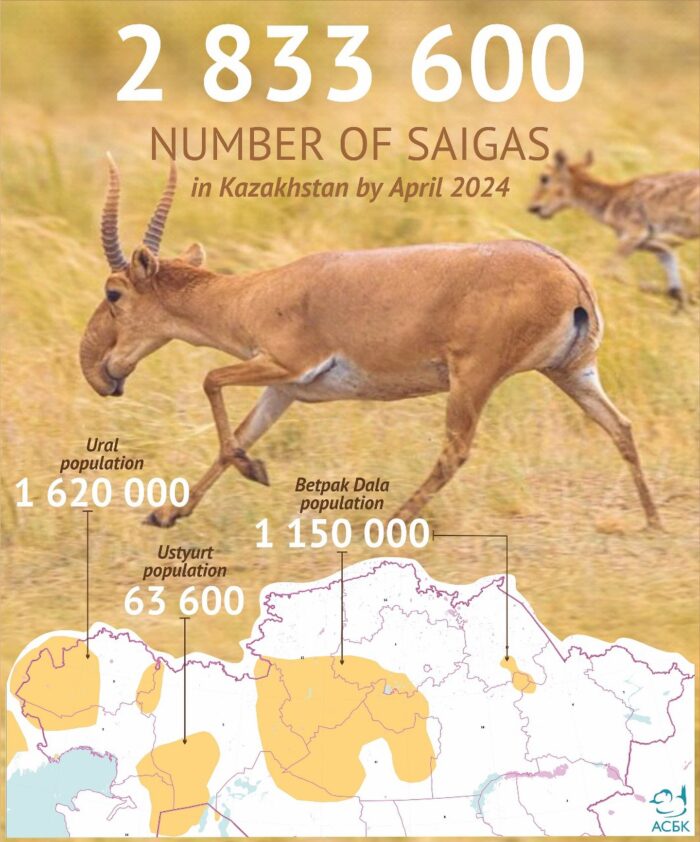

Established in 2006, the program initially focused on the saiga antelope, a key animal in the steppe. At the time, it was in critical condition, with fewer than 40,000 individuals remaining. The initiative brought together national, public, and international organizations to combine efforts for saiga conservation.

Saiga conservation efforts have caused a heated public debate in Kazakhstan at the time. Photo credit: ACBK

Over time, the program has expanded to include other key steppe species, such as gyrfalcon and steppe eagle, which are primarily found in Kazakhstan.

Altyn Dala also includes efforts to reintroduce ungulate species that once roamed the Kazakh steppes, such as the Przewalski’s horse and the kulan.

“We are currently relocating kulans from southern Kazakhstan to central Kazakhstan to restore their populations there,” she added.

Uniqueness of Kazakhstan’s biodiversity

Kazakhstan is the world’s ninth-largest country. Data from Kazakhstan’s Forestry and Wildlife Committee indicate that specially protected natural territories occupy more than 10% of its land surface or 29.3 million hectares.

Its vast territory, which spans different landscapes and ecosystems, creates challenges in protecting wildlife.

“Kazakhstan is a large country, encompassing a wide range of landscapes and ecosystems. We have mountains, highlands, and forests. (…) We also have deserts, semi-deserts, and, of course, the vast steppes,” she said.

The steppes, according to Voronova, are among the last remaining in the world that are still in their natural state and in such good condition. “People might think of Mongolia, but it is important to understand that the sheer number of livestock there has led to overgrazing in many areas, causing degradation of the grasslands. The rich, grassy pastures that once existed are now very rare,” she added.

Voronova also emphasized Kazakhstan’s role as a critical habitat for wildlife. “Moreover, three major bird migration routes pass through Kazakhstan, making our country both a wintering ground for birds but also a critical stopover for many bird species,” she noted.

The country hosts a rich variety of wildlife, including over 800 species of vertebrates. This includes more than 170 species of mammals, nearly 500 species of birds, and 100 species of fish. Photo credit: the website of the Forestry and Wildlife Committee

Kazakhstan’s vast territory, its varied landscapes, and relatively low population density mean that the nation still has space for nature.

“The challenge now is how to use and conserve these spaces effectively,” she added.

Challenges to Kazakhstan’s biodiversity

When asked what struggles specialists in the field face, Voronova noted the difficulty of collecting systematic and reliable data.

“For instance, when spring hunting was banned in 2017, it sparked enormous debates over whether we should be hunting in the spring at all. The data at the time showed a significant decline in waterfowl populations, which hunters disputed, claiming the data was unreliable. In reality, their skepticism was justified—we didn’t have trustworthy data,” she said.

This lack of reliable information creates a major obstacle in making informed decisions.

Voronova said the association is currently working on the development of a national biodiversity strategy. Photo credit: Voronova’s personal archive

“It is like trying to spend money without knowing how much you have. The same goes for setting hunting quotas or making other important decisions. While we do have data on some species, such as the snow leopard, where regular funding is provided through various projects, many other species are not adequately monitored,” said Voronova.

Another significant challenge is the development of infrastructure, particularly linear infrastructure such as power lines and wind farms, which impact birds and other wildlife.

“We have seen how power lines affect birds, and now, with the expansion of wind energy, it is affecting not only birds but also bats and other biodiversity,” she added.

Linear infrastructure such as roads and railways disrupts migration routes for land animals. An example of this was evident from saiga antelopes. Since 2009, the association has been running a satellite tagging program for saiga antelopes, using GPS collars to track their movements twice a day.

Tagging saigas is challenging, as ACBK specialists must do it very quickly to minimize the stress on the animals. Photo credit: Abduaziz Madyarov

“This data has been instrumental in expanding protected areas specifically for saigas. It has also helped understand their seasonal movements and plan infrastructure projects like highways more effectively,” she said.

One of the cases when having reliable data can help make informed decisions involved a proposed highway project that would connect central and west Kazakhstan. A section of that road was supposed to pass through the untouched steppe, critical for saiga migration.

“We launched a major campaign, including a dedicated website, to inform investors and planners about the high environmental risks. Ultimately, the project was halted officially due to lack of funding. But when they came back later to international investors, the widespread availability of information about its environmental risks likely played a role in deterring further investment,” she said.

Using modern technologies to fill the gaps in data collection can be instrumental. This includes using drones, satellite imagery, and even DNA sampling from water bodies to monitor biodiversity.

“By taking a few samples from a lake, we can extract all the DNA present in the water—whether from fish, birds, or even a wolf that crossed a river—and quickly identify every species living there,” said Voronova.

This method offers much higher accuracy than traditional techniques and could help inventory the biodiversity of Kazakhstan’s water bodies in a fraction of the time.

How does climate change impact biodiversity?

When asked about the impact of climate change on wildlife and ecosystems, Voronova acknowledged its significant effects.

Biodiversity faces adverse impacts from extreme weather events and higher temperatures—all due to climate change. Both are closely intertwined and, along with pollution, are two of the three planetary crises, as the United Nations deems them.

“We modeled the future distribution of species like the toothed frog, one of the few endemics living in the mountains of Kazakhstan, near the border with China. This small amphibian, a type of salamander, inhabits freshwater high-altitude rivers. The rapid melting of glaciers due to climate change is altering the chemical composition of these rivers, which in turn affects the salamander’s habitat,” Voronova explained.

Ranidens sibiricus, commonly known as the Toothed Frog, is included in the Red Book of Kazakhstan. Photo credit: ACBK

“In dealing with climate change, there is the same issue of lacking reliable data to conduct a thorough analysis,” she said.

She pointed out that even the migratory patterns of geese are changing year by year, depending on the conditions of the lakes they rely on. “The drying up of lakes is partly linked to climate change,” she added.

National Biodiversity Strategy of Kazakhstan

At the United Nations Biodiversity Conference in Montreal in December 2022, 188 governments, including Kazakhstan, agreed on a new set of goals to combat nature loss through 2030, dubbed the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

It sets out 23 ambitious targets, including protecting 30% of the world’s land and sea areas, restoring 30% of degraded ecosystems, reducing pollution, and curbing species extinction.

Unlike the Paris Agreement, which binds governments to achieve targets and report on them, reaching the targets set out in the biodiversity framework is voluntary.

According to Voronova, countries were expected to return home and update their national strategies to align with these global goals before the next meeting.

“Kazakhstan, however, didn’t have an existing strategy to update. There was only a draft strategy developed under a Global Environment Facility project facilitated by the UNDP in Kazakhstan. Due to various internal administrative barriers and a lack of readiness from the government at the time, this document was never officially adopted,” she explained.

Now, with a renewed international push, Kazakhstan has revisited this issue.

“The Global Environment Facility provides funding to countries for developing these strategies, often through accredited agencies like the UNDP. In this case, they received funding, announced a tender, and we were selected as the developers of this concept,” said Voronova.

In June, Astana hosted a roundtable discussion on the country’s strategy. She emphasized that this process involves a team of experts from various fields, including key figures from the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources, the Ministry of Agriculture, and other relevant government bodies. The strategy covers a broad spectrum of responsibilities.

“It is important to understand that this should not be seen merely as a document from the Ministry of Ecology,” she added.

She also highlighted that environmental education, including raising awareness about environmental issues and training environmental specialists, will be a key focus of the new strategy. Voronova acknowledges a significant shortage of personnel in wildlife protection.

Since 2022, ACBK runs a project, called Students for Nature, to increase the potential of Kazakh students in the field of nature protection. Photo credit: ACBK

The GBF includes commitments to mobilize at least $200 billion annually for biodiversity conservation. International financial flows from developed to developing countries are projected to reach $20 billion by 2025 and $30 billion by 2030.

According to UNDP, from 2015 to 2022, funding for biodiversity conservation programs in Kazakhstan reached 1.8 billion tenge (US$3.8 million). The required budget to meet the needs for biodiversity conservation and fulfill national targets is estimated at over $851 million.