Everything You Need to Know About Ulus of Jochi

Editor’s note: Discover Kazakhstan is a column dedicated to exploring the rich cultural heritage and natural wonders of the country. Each article explores various aspects of Kazakh life and history, offering insights and stories that highlight the unique significance.

Batu Khan/from open access.

The birthplace of Kazakh statehood

This year, Kazakhstan commemorates the 800th anniversary of the Ulus of Jochi, a pivotal chapter in its rich history. Established in 1224 by the legendary Genghis Khan as an inheritance for his eldest son, Jochi, this vast domain stretched across the Eurasian steppes, encompassing the Volga region, Russia, the Black Sea, and the Caucasus. Under the leadership of Jochi’s son, Batu, the Ulus (or the State) flourished and eventually became the largest state in medieval Europe, laying the groundwork for the future Kazakh Khanate and shaping the cultural and political identity of the region.

A 1562 map. Russiae, Moscoviae et Tartariae Descriptio by Abraham Ortelius, Antwerp, 1592/Wikimedia Commons.

What do we know about Jochi?

Born in the 1180s, Jochi was the eldest son and presumed heir of Genghis Khan. However, his successes sparked jealousy in his brother Chagatai, who questioned Jochi’s legitimacy due to their mother’s capture prior to his birth. Despite this, Jochi held a high position, referred to as Ulus-idi (ruler of the ulus) or khan, signifying his authority.

Jochi’s domain encompassed northern Khwarazm, Turkistan, and parts of modern Kazakhstan, and evidence suggests he expanded his conquests further west, possibly participating in the Battle of the Kalka River against Cumans and Russian princes in 1223. His mysterious death in 1225 or 1227, attributed to either a hunting accident or poisoning instigated by Chagatai, adds to the intrigue surrounding his life.

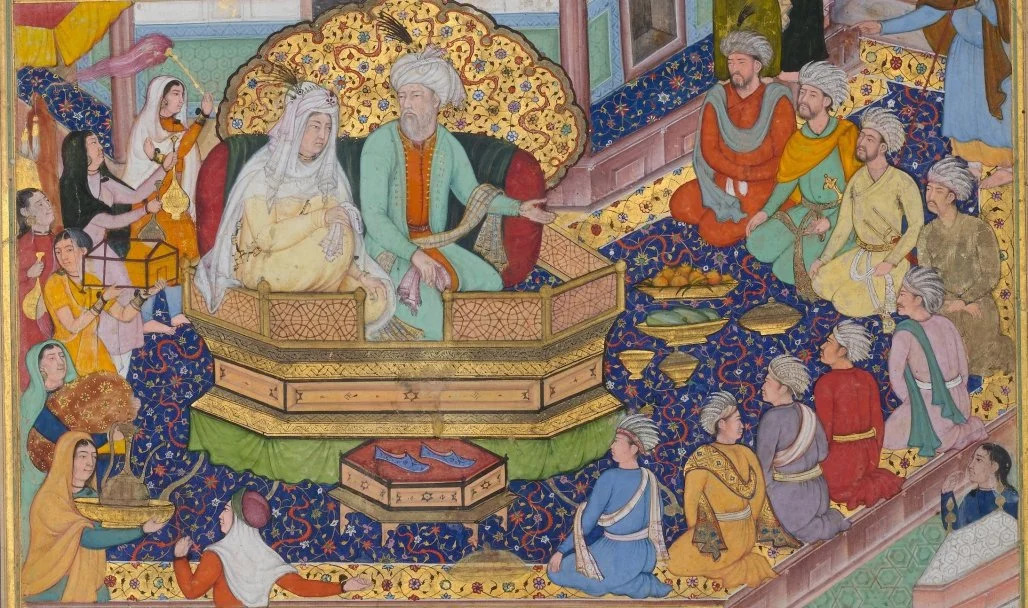

Genghis Khan, Borte and their sons. Miniature of the late 16th century/Wikimedia commons.

Origin of the name

Batu Khan (c.1207-55), Mongol ruler, 1871 (engraving). Batou, illustration from ‘The Travels of

Marco Polo’ by Marco Polo and Rustichello da Pisa, translated by Henry Yule, first published

1871)/Wikimedia Commons.

While historians often refer to the Ulus of Jochi as the Golden Horde, this name emerged much later in Russian sources around the mid-sixteenth century. The term “horde,” denoting a camp or headquarters, gained the “Golden” epithet through accounts of opulent tents, particularly the gilded tent of Özbeg Khan.

The Golden Horde was characterized by the prominent role of women, who actively participated in state affairs and ceremonies, challenging traditional norms. Wives of khans held positions of high esteem and influence, defying stereotypes of seclusion.

The state was also known by other names like the Great Ulus, Dasht-i Kipchak (Kipchak or Cumanian Steppe), and Tataria. In Western narratives, Tataria was often associated with the mythical “Tartary,” reflecting the awe and fear inspired by the Mongol conquerors.

An Empire is not easy

The Mongol Empire’s vastness posed significant challenges in governance and communication. Maintaining control over territories spanning immense distances proved difficult, even with a sophisticated postal system. Internal conflicts and power struggles among the descendants of Genghis Khan eventually led to the empire’s fragmentation.

Genghis Khan is on the throne. Persian miniature of the 15th century/Wikimedia commons.

The Ulus of Jochi, while rich in pastures but seemingly desolate compared to other uluses, displayed remarkable resilience due to its lack of powerful local elites and a strong central authority. The khan’s family maintained dominance, contributing to relative stability until internal strife and external pressures triggered its decline in later centuries.

At its peak in the fourteenth century, the Golden Horde had an estimated population of 15 million, surpassing any European country at the time. However, the population density was low, with vast stretches of land appearing desolate to travelers.

The Mongols, despite their conquests, were pragmatic rulers who adopted administrative practices from conquered nations. They relied on local officials and implemented systems like census-taking to manage their vast empire.

Nomadic cities

While the Mongol elite maintained a nomadic lifestyle, the Golden Horde saw the development of cities along trade routes, driven by economic and administrative needs. Sarai, the capital, was a magnificent metropolis, potentially larger than Constantinople and Paris in its heyday. It boasted a diverse population, bustling markets, and architectural marvels like the khan’s palace, Altuntash. However, the city’s lack of fortifications made it vulnerable to attacks.

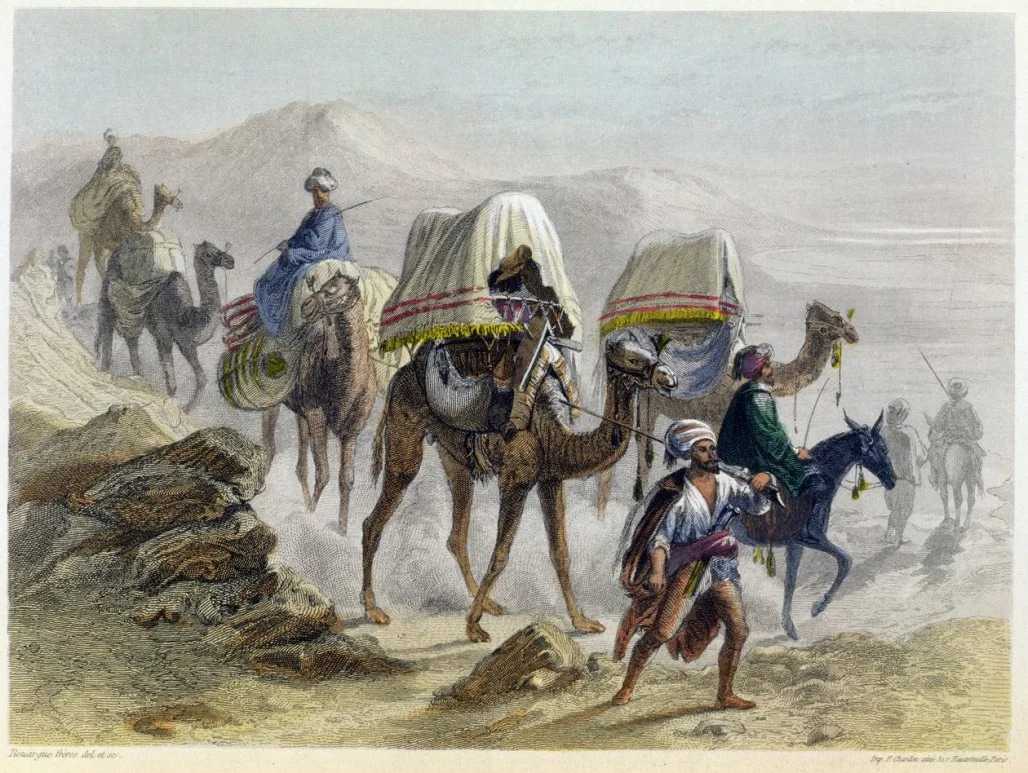

The Camel Train, from ‘Constantinople and the Black Sea,’ engraved by the Rouergue brothers,

1855/Wikimedia Commons.

State system

The power of the Jochids rested on the authority of Genghis Khan and the belief in the divine right of his descendants. The Golden Horde was divided among Jochi’s fourteen children, with the khan holding supreme authority. The state was organized into military districts and relied on a combination of Mongol and local administrative practices.

Kazakbay Azhibekuly “Kaganat,” Kurultai/e-history.kz.

Over time, a new administrative pyramid emerged, incorporating elements from conquered regions like Khwarazm. This system included a vizier and a diwan, responsible for civil administration, taxation, and revenue distribution. The Mongols’ flexibility in adopting administrative practices from different cultures contributed to the stability and longevity of the Golden Horde.

Ulus of Jochi’s Enduring Legacy

The Ulus of Jochi’s legacy extends beyond its political and economic achievements. The cultural fusion between Mongol and Turkic traditions within the Golden Horde left a lasting impact on the development of the Turkic languages and paved the way for the Turkic Age in Asia.

Mausoleum of Jochi Khan/Wikimedia commons.

The Jochids’ decentralized governance model, reliance on local officials, and integration of diverse peoples laid the groundwork for the emergence of new states, most notably the Kazakh Khanate. The legacy of Jochi Khan, 800 years later, continues to shape the cultural and political landscape of Kazakhstan, a testament to the enduring power of his vision and leadership.

Based on an original article by Nikolay Uskov, famous journalist and medievalist historian, PhD in history. The full article can be found on the Qalam project website.