Project woes spotlight reliability of Pakistan as an ‘all-weather’ partner for China

For that to happen, the committee said widespread human rights violations by Pakistan’s security forces and allied tribal militias, including enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings, have to cease.

The protests enraged Pakistan’s powerful military, with chief spokesman Lieutenant General Ahmed Sharif Chaudhry on Monday calling the BYC a “proxy of terrorist organisations and criminal mafias and nothing more than that” at a press conference held soon after the Chinese delegation met with Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif.

The divergent positions of the Pakistani state and Baloch activists contrasted with Yang’s expressed view on July 30 that “without the stability of Balochistan, there’s no stability of Pakistan”.

Yang, China’s consul general in Karachi, reiterated Beijing’s recent warnings that future investments under the envisioned US$65 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) programme launched in 2016 depend on Islamabad’s ability to protect Chinese nationals and businesses working in the country.

“Without security, there is no guarantee of development,” Yang told journalists at a press conference in Karachi, Pakistan’s largest commercial hub and home to the country’s two busiest ports.

The security threat to Chinese nationals in Pakistan has grown in tandem with the development of CPEC, with 17 Chinese nationals killed in three terrorist attacks in northern Pakistan and Karachi over the last three years.

The casualty figure would have been much higher if Pakistani security forces had not averted many other attacks, including an assault on Gwadar port in March by Baloch rebel suicide squads that took several hours to repulse.

Pakistan’s failure to deliver on its promises to China before the 2016 launch of CPEC to ensure security and political stability has been compounded by the mismanagement of its economy and CPEC.

Billions of dollars of CPEC “early harvest” infrastructure and power generation projects boosted Pakistan’s economic growth rate to nearly 6 per cent in 2018 but the record imports of Chinese machinery also created a balance of payments crisis that the country is still struggling to overcome.

The three countries recently agreed to another year-long extension for US$12 billion worth of loans and central bank deposits to consolidate Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves, finance minister Muhammad Aurangzeb said on Tuesday.

This cleared the way for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to approve Pakistan’s request for a US$7 billion bailout package covering the coming three and a half years, he said. But Islamabad had assessed further annual rollovers would be required during that period, he added.

Under IMF pressure to further reduce the debt burden on Pakistan’s finances, Prime Minister Sharif on August 2 said he had requested Beijing for a repayment extension of five to eight years for the US$15 billion that Islamabad borrowed to finance CPEC early harvest power projects.

Islamabad already owes the Chinese corporate operators of these power projects about US$2 billion in back payments, prompting state-funded insurance firm Sinosure to withhold guarantees for new CPEC projects.

Nonetheless, Islamabad is pressing Beijing to persuade Chinese independent power producers to renegotiate and soften the terms of their agreements.

Pakistan’s multiple failures to live up to its CPEC commitments have raised questions about its reliability as an “all-weather strategic partner” of China.

Josef Gregory Mahoney, a professor of politics and international relations at East China Normal University in Beijing, sees them as evidence of a “double game” that Pakistan has “long played” between China and the United States.

While it was not a new source of tension between Islamabad and Beijing, he said the “broader problem is that Pakistan perpetually puts itself … in a slippery position, one that favours its strategic interests in some respects while also accommodating a lack of firm resolve to deal effectively with entrenched issues, from rampant corruption to complicated relations with India and Afghanistan”.

Mahoney said neither Washington nor Beijing wanted to abandon Islamabad, but “both are regularly frustrated”.

Unlike some countries that “play a double game with the US and China to find a strategic balance” as well as opportunities for growth and development, “Pakistan seems to play this game as a means to perpetuate its systemic problems”, he told This Week In Asia.

However frustrated Beijing might be with Islamabad, it would not have been surprised by its shortcomings, said Yun Sun, director of the China programme at the Stimson Centre, a Washington think tank.

“Pakistan has always been a challenging country. There is no illusion in China about that from the beginning,” she said. “Pakistan is always going to be China’s partner and its strategic importance will not diminish.”

But with the current ups and downs of the relationship, she expects China to be “more careful about its financial involvement” in Pakistan.

The next stage of CPEC, which is focused more on building Pakistan’s industrial capacity through the relocation of Chinese manufacturing, will not require the multibillion-dollar investments made during the hard infrastructure-focused early phase.

“I don’t think China will be allocating as much loans and investments as before, but it will not stop providing financial resources,” Yun told This Week In Asia.

According to Mustafa Hyder, executive director of the Pakistan-China Institute in Islamabad, Beijing still has “complete trust and faith” in Islamabad as “its best friend in its international partnerships”.

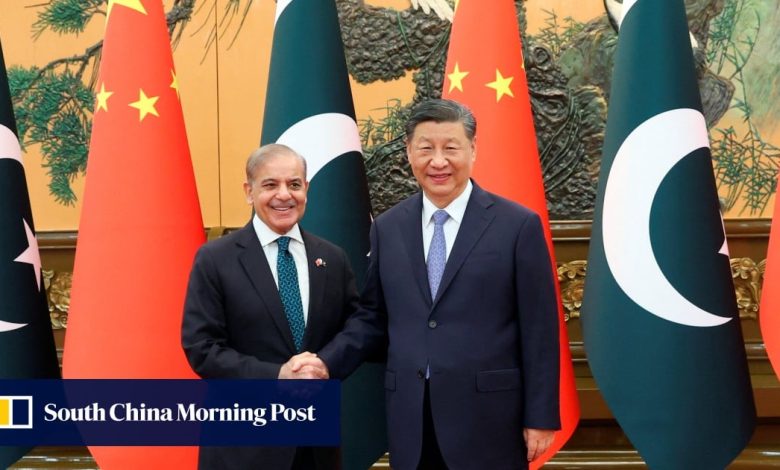

This was reflected in the joint statement issued during Prime Minister Sharif’s visit to China in June, he said.

“However, Pakistan has not been able to deliver on CPEC like it could have and should have,” Hyder said.

Most pressing is the security threat faced by Chinese enterprises and nationals, for whom it has become “very difficult to just move around, let alone do business” in Pakistan, he said.

Security problems and Islamabad’s failure to uphold the terms of its agreements with CPEC independent power producers have “led Chinese enterprises to consider other options – such as Asean countries – as their investment destinations”, Hyder said.

But CPEC-related problems should not be seen as reflective of the overall bilateral relationship between China and Pakistan, he said.

“These are two separate things which are often mixed up and confused as one, which they are not,” Hyder said.