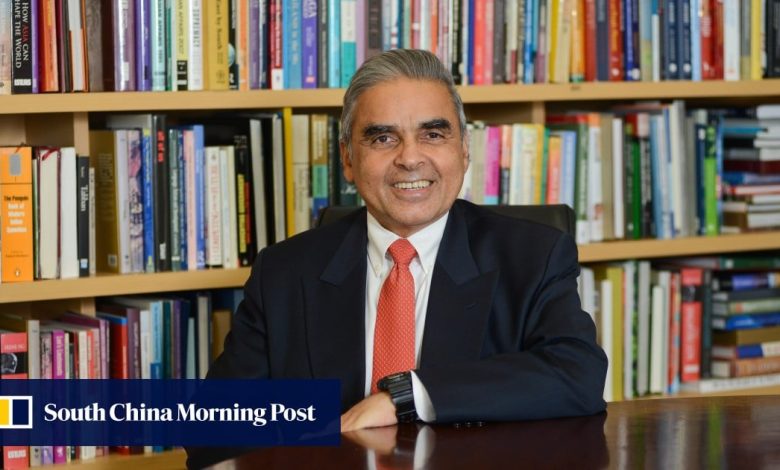

Kishore Mahbubani in his memoir: the rebel undergraduate who took on Lee Kuan Yew

“My most visible contribution to university life as a whole came when I was appointed as the editor of the student newspaper, the Singapore Undergrad. As editor, I discovered that I had a provocative streak. The politically apathetic students of my time had no interest in student newspapers. Hence, I tried to increase interest in the paper and to encourage greater debate and reflection by choosing provocative headlines. The most memorable editorial decision I made was to leave the entire front page of the paper blank and print in the middle of the white page a headline in small print: “Are we really this blank?”

Initially, I floated this article as an editorial representing the views of the paper. While the other editors liked the piece, they suggested that I publish it in my own name instead. I agreed. It was an act of folly.

My fellow editors were obviously smarter than I. They knew well that the PAP government of that time was not tolerant of dissent or criticism and that there could be serious consequences for writing such strong and direct criticism of the PM. If I had been squashed, in one way or another, after publishing this article in my name, my fellow students would not have been surprised.

Indeed, some time after I published this article, I was told that Vice-Chancellor Toh Chin Chye – who had been the founding chairman of the PAP and had only recently stepped down as deputy prime minister (DPM) – had said, “Tell Kishore not to take me on. If he does, I will crush him.”

Instead of being squashed, I became a celebrity after publishing the article. The New York Times (NYT) correspondent in Singapore, Anthony Polsky, came to interview me on campus. The BBC followed suit. Equally importantly, my fellow students began to treat me with greater respect. I was no longer an obscure philosophy student, as everyone knew who I was.

My celebrity status was further enhanced when I decided to shave my head. My bald head had a kind of electrifying effect, and the campus began speculating about why I had staged a major protest against the government by adopting the shaven appearance of a monk. Actually, it was a complete accident.

As I was turning twenty-one in October 1969, my mother decided that I should undergo an important Hindu ceremony symbolising the transition from boyhood to manhood. When I asked my mother how to prepare for this ceremony, she said that I had to go for a haircut and told me that the tradition was for boys to be shaved completely bald. So when I went to the barber on East Coast Road, I told him to shave everything. When I made the request, I assumed [quite foolishly] that he would cut my hair down slowly, and I could stop him if I felt uncomfortable. Instead, he took out an electric shaver and immediately created a bald strip through my hair. There was no turning back.

So I arrived bald on campus, creating a memory that many of my fellow students still speak about. My growing reputation as a public critic of the Singaporean government didn’t hurt me. It may even have helped me because the Singaporean government had an unusual policy of recruiting dissenters.

Tommy Koh, who preceded me as Singapore’s ambassador to the United Nations, and Chan Heng Chee, who succeeded me in that post, had both challenged government policies before joining the MFA–Tommy in his capacity as a member of the University Socialist Club and president of the University of Malaya Students Law Society and Heng Chee by writing a book arguing that the PAP’s consolidation of power had weakened democracy in Singapore. Another outspoken critic was David Marshall, the founder of the Worker’s Party, Singapore’s second major political party after the PAP. He was recruited as Singapore’s ambassador to France and served in that post for fifteen years.

This big-tent policy may have been the reason why Goh Keng Swee, who was then the minister of defence, invited me to join his team of “whiz kids” in the Defence Ministry and promised that I would have a great career there. This was obviously an amazing offer for a recent graduate. However, I foolishly told him the truth: that I could not take up his offer, as I was a pacifist. He gave me a look of total contempt and threw me out of his office.”

Excerpted from Living the Asian Century: An Undiplomatic Memoir by Kishore Mahbubani, published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group. Available at local bookstores.