Philippines turns to maritime law for legal teeth against China

When Congress approved the latest version on July 17, maritime law expert Jay Batongbacal described it as a “foundational law”, setting out in clear terms “the Philippines’ adherence to Unclos [United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea]”.

While the draft law has made no mention of China, its main sponsor, Senator Francis Tolentino, who guided its passage through Congress, told colleagues on November 28 last year: “May I just also remind my dear colleagues of the many incidents of aggression from our Chinese counterparts that we have experienced recently in the West Philippine Sea.

“It is time we take a stand against this bullying. With the passage of this Maritime Zones Act, we are taking a firm stand.”

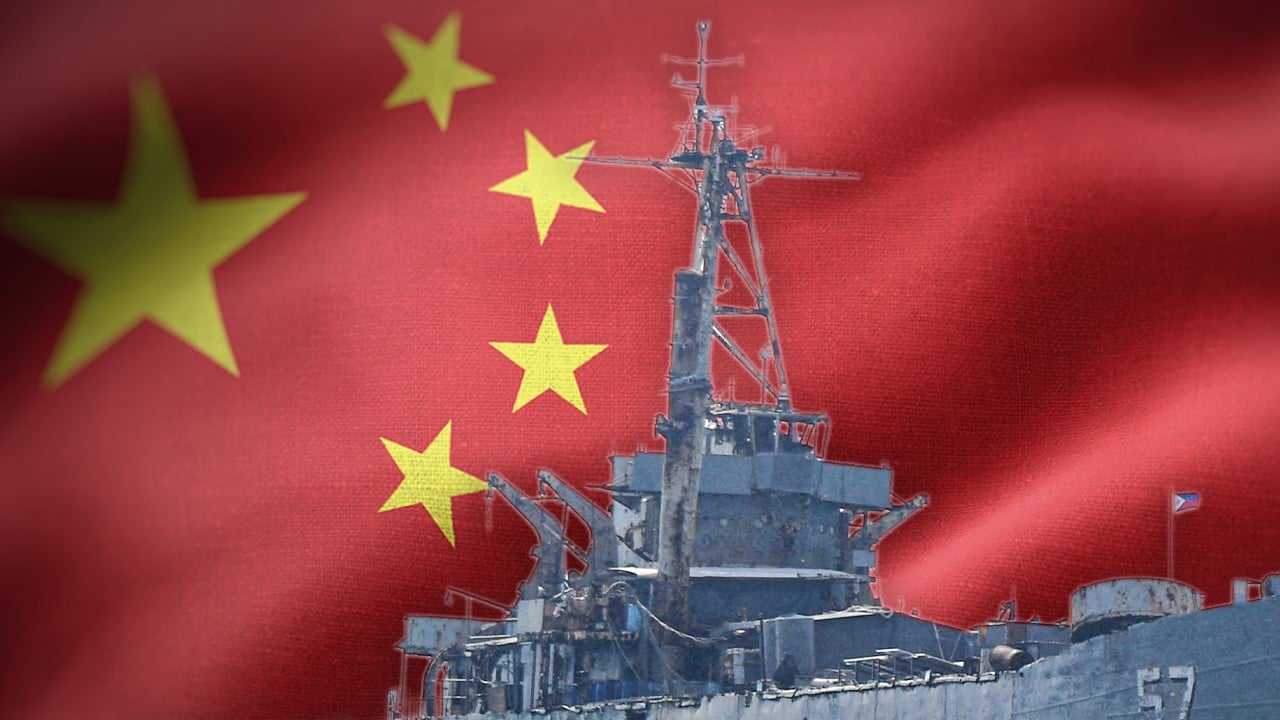

Two weeks before Tolentino’s comments, the Chinese coastguard had chased, surrounded and blasted with powerful water cannons at a Philippine coastguard ship and other vessels resupplying the BRP Sierra Madre, a grounded warship serving as a military outpost for Manila on the Second Thomas Shoal.

When the Philippine Senate approved the law on February 28 this year with all senators voting “yes”, China filed a diplomatic protest against its passage.

“China firmly opposes it and has lodged solemn démarches to the Philippines,” its Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokeswoman Mao Ning said during her March 5 daily briefing.

Xinhua state news agency quoted Mao as saying the proposed law was an attempt to enforce the “illegal” 2016 arbitral award, in which The Hague dismissed Beijing’s claims to the South China Sea.

“Under the pretext of implementing Unclos, the Philippines has advanced the legislation of the ‘Maritime Zones Act’ in an attempt to put a legal veneer on its illegal claims and actions in the South China Sea,” she said.

In response to China’s assertions, Tolentino held a press conference on March 6, arguing: “China has no right to veto this. China cannot stop this law.”

Lines drawn

The latest version of the legislation, sent to the president for approval, defines the Philippines’ maritime zones and entitlements within each area.

Based on a copy obtained by This Week in Asia, it divides the waters in and around the Philippine archipelago and 7,641 islands – the second largest archipelago in the world after Indonesia – into “maritime zones”.

For instance, in the zone called “territorial sea”, which extends up to 12 nautical miles from the baselines and includes the airspace above and the seabed and subsoil below, Manila exercises sovereignty but recognises the right of foreign vessels to undertake “innocent passage”.

Beyond this territorial sea up to 24 nautical miles from the baseline is another maritime zone called the “contiguous zone” where Unclos allows Manila to exercise control to “prevent infringement of its customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws”.

The belt of water, up to 200 nautical miles from the baselines, is the country’s EEZ where it can exploit the seabed and subsoil, name underwater features, conduct scientific research and construct artificial islands.

In an older version, the proposed measure asserted that “all artificial islands constructed within the Philippine EEZ shall belong to the Philippine government”.

In the version sent for the president’s signature, the phrase has been removed and replaced with a line that states: “Pursuant to Articles 56 and 60 of the Unclos, the Philippines has the exclusive right to construct and to authorise and regulate the construction, operation, and use of artificial islands, installations and structures, and has exclusive right and jurisdiction over such artificial islands, installations and structures.”

Retired Supreme Court senior associate justice Antonio Carpio told This Week in Asia on Tuesday that this section “merely restates international law as a warning to violators – that illegally built structures cannot acquire legal status despite the passage of time and can be confiscated or removed any time by the legal authority that has jurisdiction over the area”.

Enforcing West Philippine Sea

Batongbacal, also the head of the University of the Philippines-Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea, said upon its approval, the law would empower the South China Sea arbitration award, “which clearly established our entitlements in the maritime zones under Unclos”.

He added: “With that act, we are also laying the groundwork for improving our law enforcement within these maritime zones.”

During the floor debates, which took place from November 2023 to February, Senator Koko Pimentel wanted to remove all mention of the arbitral victory. But Tolentino stood his ground, saying it was important to include it because “the ruling granted the Philippines a full 200 nautical mile EEZ measured from the baselines of Palawan”.

Its inclusion in the Maritime Zones Act “would clarify the boundaries of the Philippines’ EEZ, ensuring the protection of Filipino fishermen within internationally recognised boundaries”, according to Tolentino. It would “counter China’s argument that the ruling lacks an enforcement mechanism” and serve as a diplomatic tool to counter Beijing’s criticism that Manila lacked a maritime zones law, Tolentino said.

Also, “mentioning the ruling in the bill would underscore China’s unlawful occupation of such artificial islands, enabling the Philippines to maintain sovereign rights and maritime dominion, even in the absence of possession,” he added, referring to the Fiery Cross Reef, Johnson Reef, Cuarteron Reef, which lie inside the Philippine EEZ and have been occupied by Beijing.

Under the proposed law, violators could face “penal sanctions” or a fine of between US$600,000 and US$1 million.

When Senator Robin Padilla inquired why Sabah was not mentioned in the proposed measure, Tolentino replied that “the claim on Sabah involves territorial issues while the proposed measure is anchored literally on UNCLOS, which does not settle territorial or sovereign disputes between states, but specifically deals with archipelagic waters.”

He said a separate legislation was needed to address Manila’s claim on Sabah but the proposed maritime law did not invalidate the claim.