Kissel and the Ancient Art of Pudding

However strange it seems today, our ancestors described ancient kissel (also spelled kisel in English) as being very different from today’s kissel. First of all, they didn’t drink it—they ate it. It was cooked down to a dense consistency. Hence the “kissel shores” celebrated in Russian fairy tales.

Second, kissel was not sweet. Its name comes from the Russian word for sour (кислый) because that’s what it was.

Kissel was made from bran, oats, rye, and peas. They covered the grains with water, let them stand for a while so that the starch was released. The released starch made the mixture swell up and become lightly fermented with a precipitate at the bottom of the container. The water was changed several times, which gave us the saying “the seventh water on the kissel” (now meaning “a distant relation”). When made with flour, the process produced a thick wort that was used to make kissel. The wort was a kind of thickening agent to which milk could be added, boiled and poured into molds where it would solidify.

Pea kissel was made simply by boiling pea flour until thickened. Fried onions, scallions and mushrooms could be added to it. After it solidified, it was a slightly jelly-like, sour dish, reminiscent of aspic.

Courtesy of authors

Here is an example to give you a better idea of what kissel was in past centuries. In “Trading on the Volga” the unfortunately now-forgotten Russian writer Pavel Zarubin (1816-1886) left vivid ethnographic pictures of everyday life in the middle of the 19th century:

“Oh, my friend, the kissel they make here is heavenly,” Kartuzov said in awe. “Our women can’t make kissel like this! Hold on a minute — let me try some.”

Kartuzov leaned down to the deck and picked up a splinter of wood, sharpened it a little, and stabbed a good-sized piece of kissel. He was going to cut it in half, but to save time he decided to swallow it whole. But he was unlucky. Either he breathed in at the wrong moment or the piece was too big. The piece of kissel stuck in his throat like a piston that had topped.

Luckily Ephraim quickly realized what was happening. As soon as he noticed that Kartuzov was choking, he quickly put his kissel down on the deck and began pound on Kartuzov’s back. This did the trick; the kissel popped back out. Kartuzov, still barely able to breathe, crossed himself.

Imagine what kissel was like in the mid-19th century if you could choke on a piece of it!

Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, the first mention of kissel dates back to the 12th-13th centuries. That doesn’t mean that kissel appeared then; it’s clearly much older. But the first time it was mentioned was in the Laurentian Chronicle, where Nestor the Chronicler describes the siege of the town of Belgorod by Pechenegs in 997. An elder addressed the starving city residents: “Listen to me, hold on for three days and do not surrender. Gather up at least a handful of oats, wheat and bran.” He told the women to make a starter for kissel, ordered them to dig a well, put the starter in a keg, and lower the keg into the water. When the Pecheneg negotiators came, the city residents pulled the keg from the well to show that there was plenty of kissel in the city. With that the Pechenegs left, realizing that the Russians would not starve to death in the fortress since they had kissel to eat.

These times are long gone.

One of the first recipes we found is in Vasily Lyovshin’s “Russian Cookery” (1795): “Take a bit rye dough when baking bread, dilute with water, strain through a sieve, boil until it begins to firm up, cool, serve with milk.” Or “Soak overnight oatmeal flour, strain in the morning, dilute with water and boil as above. Cool and serve with milk.”

This kind of kissel held an important place in Russian life. It was not just a dish, but a part of the fabric of life. Unfortunately, all the tradition around it — both ceremonial and in everyday life, — are part of the past. Only the names of Moscow streets remind us: We still have Lower, Big, and Small Kissel Lanes, and even Kissel Dead End. Kisselniki (kissel makers) lived there and worked, mostly producing kissel for the monasteries nearby. Vladimir Gilyarovsky, a connoisseur of old Moscow, wrote that you could find trays of the favorite oatmeal and peas kissel all over the city. It was always served in taverns where people could be heard shouting, “Thicken up the pea kissel with hemp or flaxseed oil!”

Wikimedia Commons

The familiar liquid kissel from berries and fruits appeared in Russia later, somewhere in the middle of the 19th century. They were made with juices, decoctions, added sugar, and brewed with starch from potatoes or corn. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries chocolate kissel was popular. Sophia Tolstaya, wife of Leo Tolstoy, included a recipe for it in her cookbook: “Grind a bar of chocolate. Take two cups of potato flour, one cup of sugar, dilute with a little cold milk, then add to 1.5 bottles of milk and boil the mixture. Rehydrate the chocolate and slowly pour it in. Stir until it pulls away from the sides of the pot. Pour into a dish and serve with cream.”

Wikimedia Commons

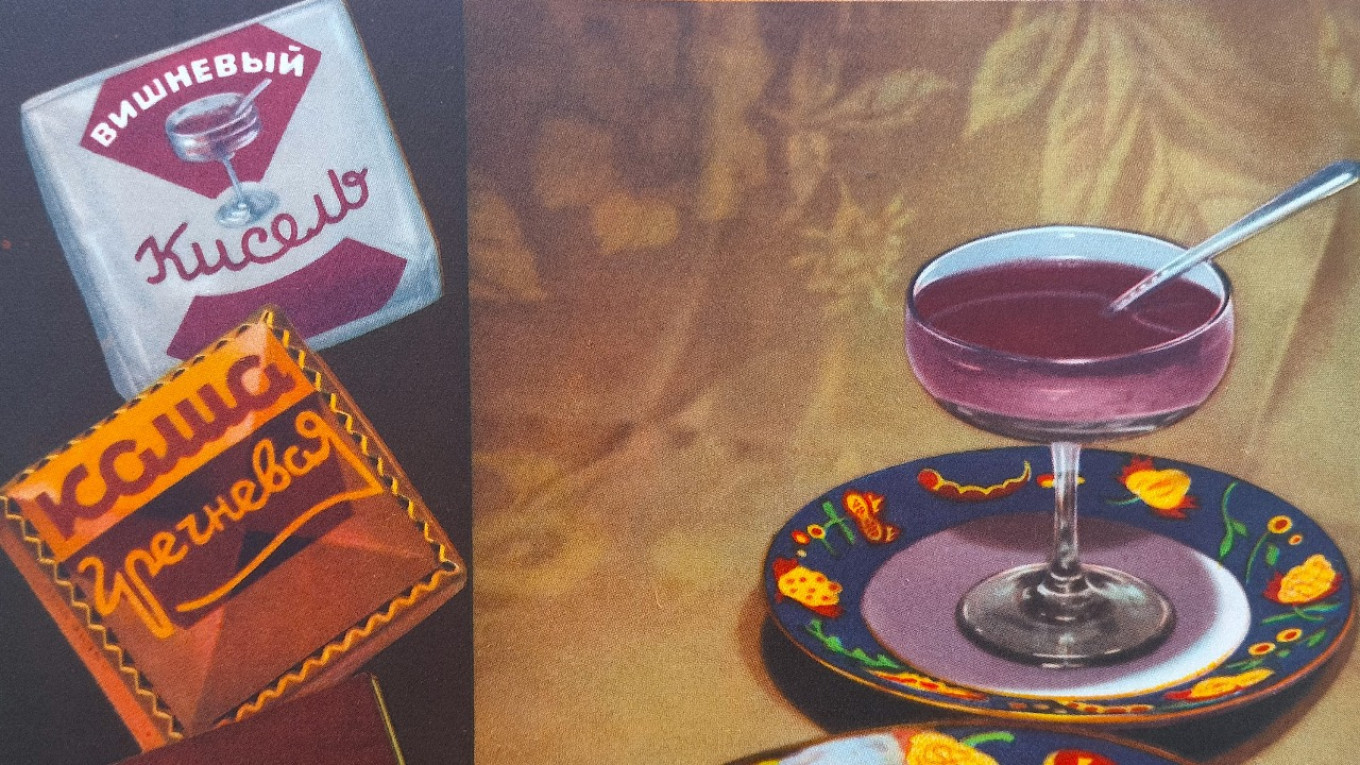

During the Soviet period, liquid kissel was mass-produced. It was served in kindergartens, schools, and workers’ canteens. When briquettes of solid kissel appeared, kissel could be made at any time. But lots of children liked to simply munch on the briquettes as an afterschool treat.

We will prepare a dish that combines two historical Russian products: baked milk and kissel made from it.

How to make baked milk in the oven

Pour milk — either pasteurized storebought milk or boiled farm milk — into a clay or cast-iron pot or a glass jar. Do not cover with a lid — otherwise condensation will accumulate and drip back into the container with milk. You can cover it with foil, but pierce the foil in several places with a knife.

Heat the oven to 80°-90°C / 175°-195°F.

Put the container with milk in the oven for 4-5 hours. The milk should not boil; it should only bubble a little bit.

The longer the milk is in the oven, the darker and thicker it becomes, but 4-5 hours is sufficient to make delicious baked milk. The surface will be covered with a beige-brown foam, which you can easily skim off if you wish.

How to make baked milk in a multicooker

Pour the milk into the bowl of the multicooker. To keep it from boiling over, put the steamer insert in the bowl to keep the milk from rising up. If you don’t have the insert, grease the walls of the bowl with butter a little above the milk level. This will also keep the milk from rising.

Cover the multicooker with the lid and select the “Stew” program for 6 hours. You can also reduce the cooking time to 4 hours and leave the “Heating” program on for 2 hours.

It is better to strain the baked milk from the multicooker to catch any solidified bits from the bottom.

Baked Milk Kissel

Ingredients

- 500 ml (1 pint or 2 cups) baked milk

- 2 Tbsp sugar

- 3 Tbsp potato or corn starch

Instructions

- Dilute the starch in 100 ml (½ c) cold milk.

- Bring the remaining 1 ½ c milk to a boil. When it is boiling, stir the cold milk with starch (the starch will have settled to the bottom as the other milk heats up) and then pour it slowly into the heated milk in a thin stream, stirring the hot milk constantly.

- Just when the mixture shows the first sign of boiling, remove from heat. Cool. Serve the sour cream warm or chilled.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office has designated The Moscow Times as an “undesirable” organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a “foreign agent.”

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work “discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership.” We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you’re defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.