Opinion | China should look back in history when it comes to chastising Japan, others about aggression

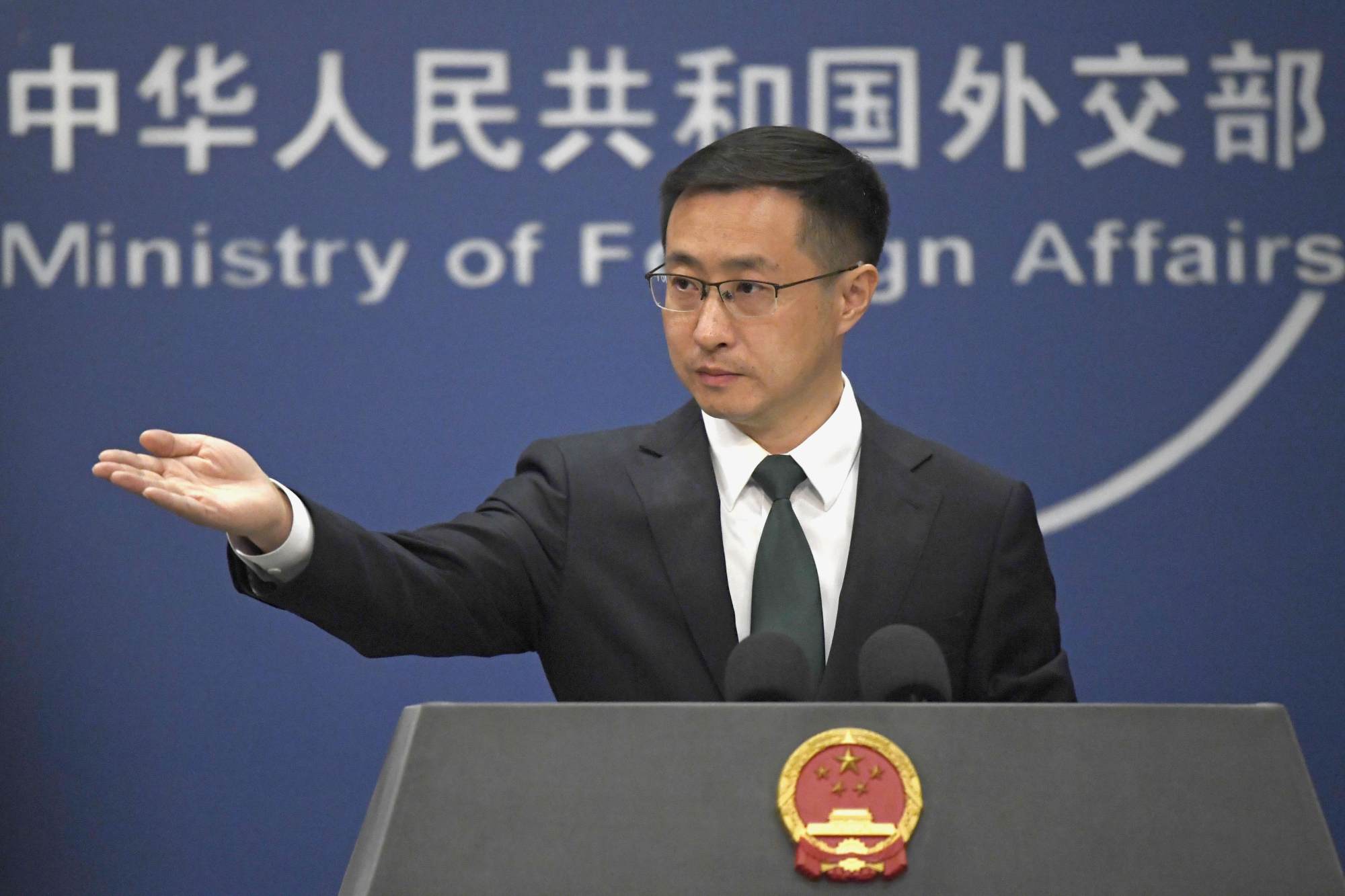

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Lin Jian said any actions that undermined regional peace and stability would “arouse the vigilance and common opposition of the people of the region”.

Japan should “seriously reflect on its history of aggression and be cautious in its words and deeds in the field of military security”, he added.

In 2014, during China’s commemoration of Japan’s World War II surrender, Beijing urged Tokyo to learn from its past military aggression.

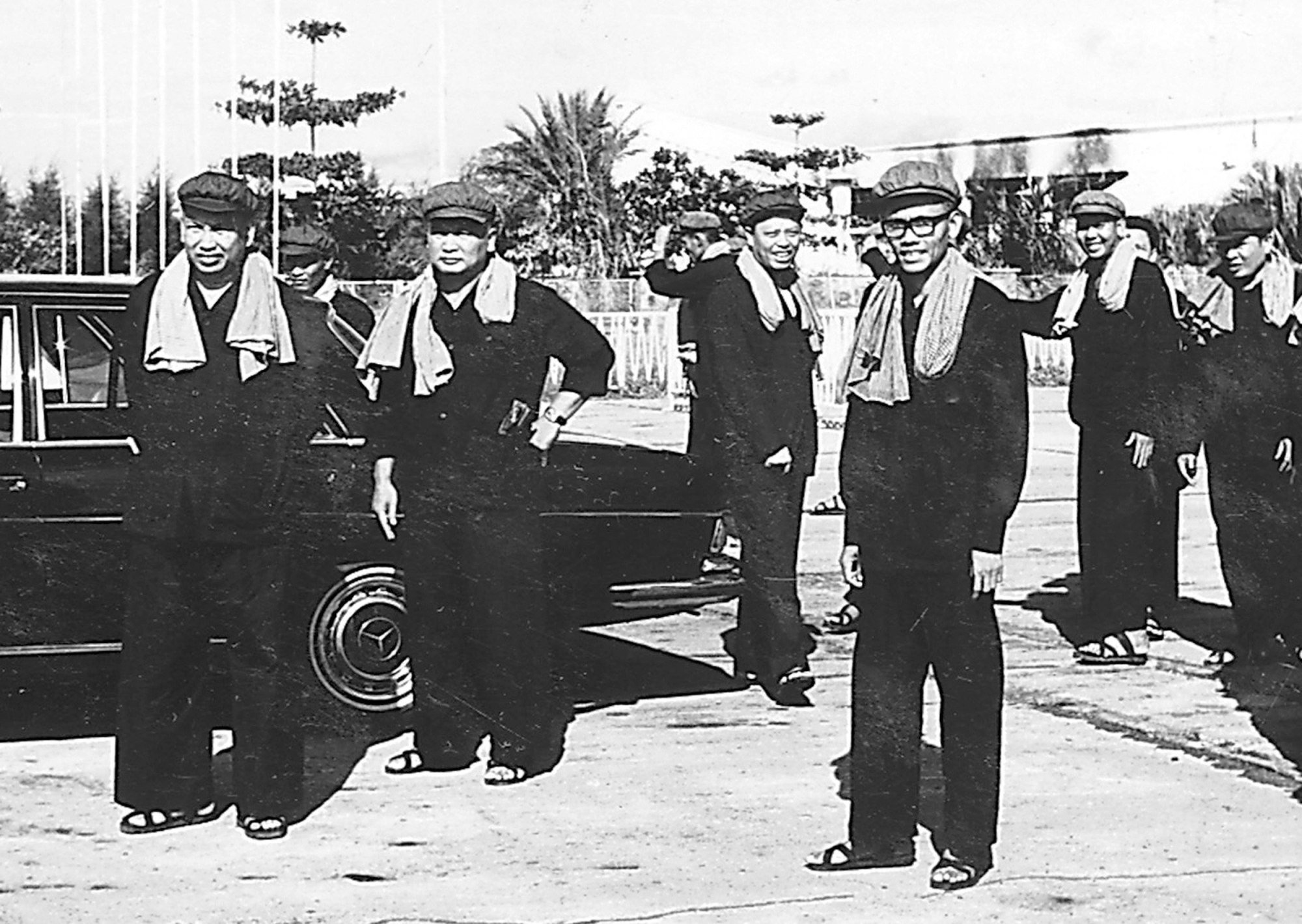

By cultivating ties with underground communist parties and supplying arms and material to these countries, Beijing hoped that armed struggle would lead to the overthrow of governments.

China’s insurgency support was a tool used to cement its international status among socialist countries, according to Stanislav Myšička writing in the International Journal of China Studies in 2015, as well as to weaken non-communist regimes, alongside the superpowers backing them.

A 1985 report from the Rand think tank said that over a period of almost 40 years, Southeast Asia governments had experienced so many insurgency incidents and conducted so many counter-insurgency campaigns that “an inventory of cases would reach encyclopedic proportions”.

Southeast Asian governments had to direct limited budgets and resources to tackle the insurgents who had little qualms about resorting to violence, including the destruction of life and property.

Remembering history is well and good, but perhaps it should be a two-way street.

Doing so is likely to allow countries and individuals to learn from the past, understand the present, and hopefully not repeat past errors.

When urging Japan to remember history, China does not necessarily have its eyes on history or past aggression. Rather, it is to make a political statement on its dissatisfaction and even resentment of the present.

By building closer defence ties, selling patrol vessels to Manila, and sending fighter jets and tanks to take part in joint exercises, Japan’s Foreign Minister Yoko Kamikawa said it was necessary to ensure “a free and open international order based on the rule of law”.

Remembering history is a convenient tool for China in expressing its resentment and exerting pressure on Japan.

Does supporting communist insurgents in Southeast Asia in this time and age sound far-fetched? Likewise, for a return to the sort of Japanese militarism, invasion and occupation found before World War II.

Perhaps history should be left to historians, academics, even activists and civic groups, because when the Chinese government harks back to history, uppermost on its mind is the present and not the past.