Bears, Borsht, Floating Pies and Other Wonders of Imperial Russian Cuisine

What is the best way to instill love for the tsar and obedience to the authorities? This isn’t just a question that puzzles Russian parliament deputies today. In the past, the solutions were simple and effective.

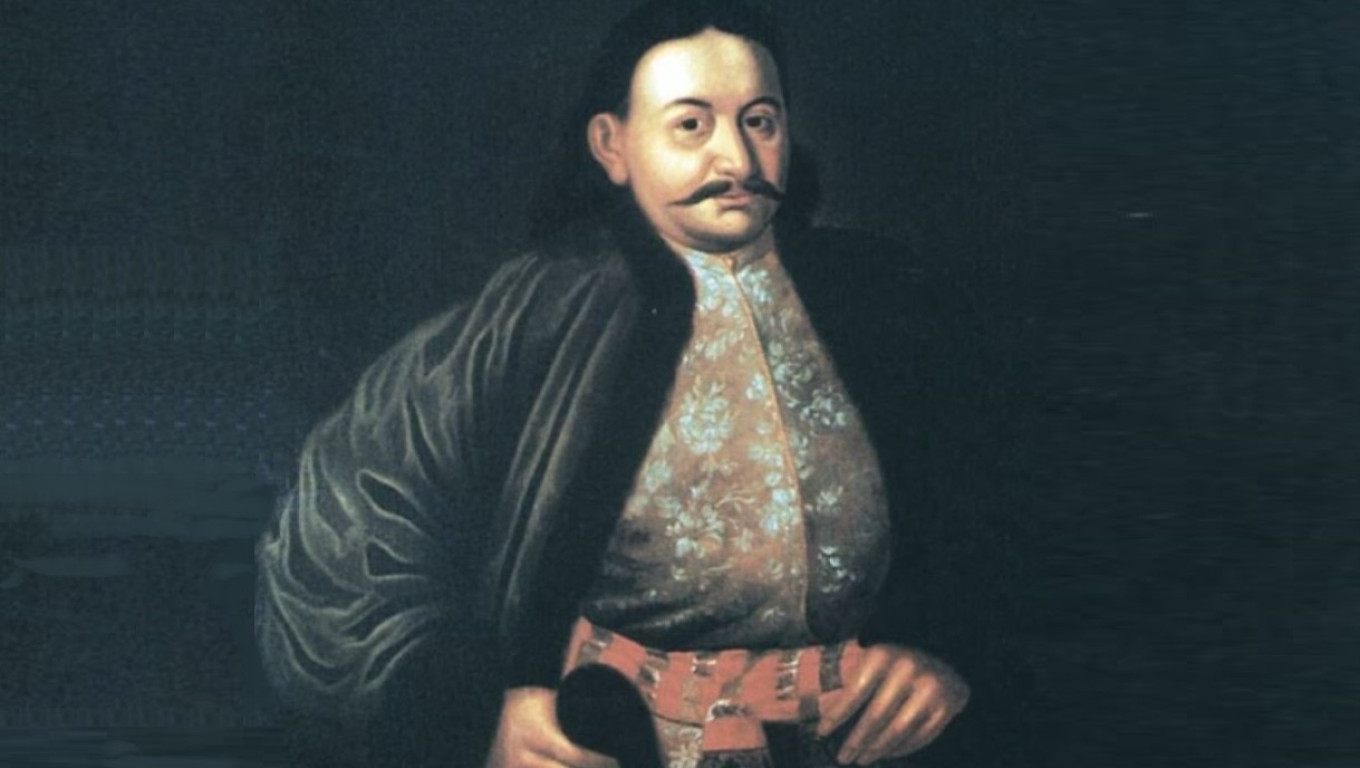

The beginning of the reforms of Peter I (Peter the Great) was not an easy period, and far from all the high dignitaries were happy to give up the habits of the old days. The tacit head of this “ancient” party was Prince Fyodor Romodanovsky. He was related to the tsar by numerous ties of kinship, and he was respected by Peter for his exceptional loyalty and shrewd (though uneducated) mind.

Occupying an important position in the state (head of the Order of Investigative Affairs, i.e., the secret police) he was given the title of Prince-Caesar and even stood in for the tsar when Peter I was traveling in Europe. But in his home circle Romodanovsky was the model of an old Russian boyar. He alone dared to oppose Peter’s will regarding changes in clothing. He always wore a Russian caftan, trimmed with gold or silver. He was rude in speech and did not change his tone of conversation with anyone. He could speak to a nobleman as sharply as to a mere mortal.

“This prince was of a species like a monster; he had the temper of an evil tyrant; he showed great unwillingness to do good to anyone; he was drunk on all days — but he was faithful to his majesty like no one else,” wrote diplomat Boris Ivanovich Kurakin (1676-1727), another close associate of Peter I.

Wikimedia Commons

Needless to say, Romodanovsky adhered to the most ancient and paternal habits in his meals. As the writer and historian Alexander Kornilovich (1800-1834) noted, before they bowed before their host the visitor, no matter what rank they held, had to drain a large goblet of simple wine seasoned with pepper and served on a golden dish by a tame bear.

To be clear: “simple wine” in those years was a distillate — more simply put: moonshine — that was 40 proof. In other words, a visitor had to drink down a glass of pepper vodka.

Wikimedia Commons

If you refused, you’d be sorry. The tame bear knew his job well. He’d grab on to the wig or hair of the visitor and would not let him go until he agreed to “accept the greeting.”

The almanac “Russkaya Starina” in 1824 printed a typical menu of those years. “Simple soup, kulebyaka with eel, boiled sterlet and mutton roasted with garlic were the main dishes at lunch at the Romodanovsky house. Hundred-year-old mead, beer infused with berries, and occasionally Malvasia wine filled golden and silver mugs placed in front of each place setting.”

There were different ways to dine out, on a hunting trip, for example. A multitude of dishes was followed by general drinking: large bowls filled with wine passed from hand to hand. The more successful the hunt, the rowdier the feast.

The method of “stick and carrot” was almost literal in Russia: the authorities tried to inculcate love for the motherland with both flogging and treats. It was not always the carrot. For example, in the time of Catherine II, contemporaries were terrified by the expression “To be invited to have some marvelous borscht.”

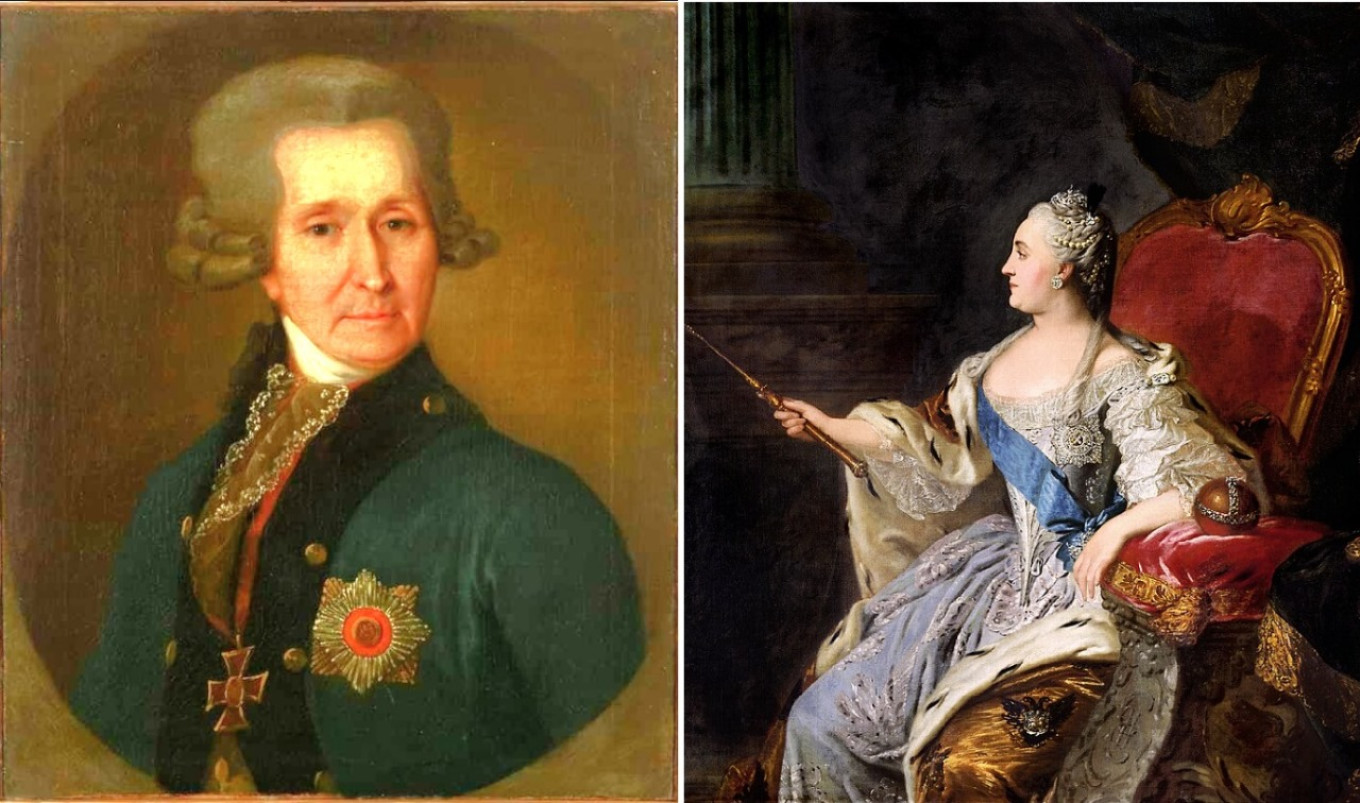

Interrogations of “especially dangerous” state criminals at the end of the reign of Catherine II were usually conducted by Stepan Sheshkovsky, the head of the Secret Expedition, Privy Counselor and confidant of the Empress. He was a petty official who in the 1770s was suddenly elevated to the top of the investigative office. Sheshkovsky transferred people of low rank and merit to his subordinates, while he carried out inquiries of prominent people. He conducted the interrogation of the writer Alexander Radishchev, called by the empress “a rebel, worse than Pugachev” for his book “Journey from Petersburg to Moscow” (1790).

Wikimedia Commons

His main trick was to soften up the victim with a heartfelt conversation, a friendly chat, one nobleman to another. As soon as the interlocutor relaxed, he was invited to enjoy some “marvelous borscht,” i.e. to be interrogated. The form of interrogation was very refined. For example, the armrest of the chair the guest was sitting in would suddenly move and snap together with the other armrest. The man couldn’t free himself or prevent the secret punishment. At Sheshkovsky’s signal, a hatch opened and the chair was lowered under the floor. Only the person’s head remained visible as the rest of the body hung below. Then the chair was removed, the person was undressed and his body mercilessly whipped. The executors couldn’t see who they were punishing. Then the person was dressed and lifted on the chair up to table level.

Such were the “borshts” during that strange time of Russian history.

By the way, the love for this kind of clever mechanism extended to feasts. The floor of the Hermitage Pavilion Hall in Peterhof is made of magnificent patterned parquet. In the evenings courtiers in their finest clothing gathered for dancing and conversation. When it was time for dinner, tables rose from under the floor. The dishes in the middle of the tables were changed the way magical transformations are done in theaters, and each diner could ask for any dish they were told was available by writing the name on a piece of slate and ringing a bell downstairs.

Pavel and Olga Syutkin

Footmen scurried about below, hurrying to retrieve the required dish from the kitchen and bring it up. Here, of course, they needed experience and excellent training so that the dishes wouldn’t be cold by the time they reached the person who ordered it. There is a legend that the list of dishes in the kitchen was huge. Only General Suvorov could cause a stir and embarrass the Empress as she boasted that anything and everything could be ordered. He would demand some “incredible” dishes, such as simple army soup and porridge.

Of course, there were always pirozhki (little pies) on the Russian table. Sometimes they were simple, straight from the oven. And sometimes they were elegant and fancy pies. These are the ones we’ll make together with you.

Rassolnik Pies (Pickled Pies)

Made with short crust pastry, this can be either one large pie or several small pies. The filling is beef or chicken, organ meat, pickles (which give rassolnik its characteristic flavor), and fried onions.

To keep the filling moist, cucumber brine is added. For beef patties, the best meat to use is tenderloin or shot loin. For chicken, use breast meat.

Cucumbers should be pickled, not marinated. And the brine should, of course, be pickling brine.

for 14-16 little pies

Ingredients

for the dough:

- 300 g (10.5 oz or 2 ½ c) flour

- 200 g (7 oz or 7/8 c) cold butter

- 200 g (7 oz or ¾ c) low-fat sour cream

for the filling:

- 400 g beef fillet

- 300 g (10.5 oz) pickles

- 150 g (1/3 lb) onions

- 100 g (3.5 oz or ½ c) butter

- 100 g (3/8 c) cucumber brine

- salt, freshly ground pepper to taste

- 1 egg yolk

- 40 g (3 Tbsp) water or milk to baste the patties

Instructions

- Pour the flour into a bowl and put the butter cut into small pieces on top. Use your hands to knead the butter into the flour until it forms crumbs. Add sour cream and knead into a firm, non-sticky dough.

- Add more flour if necessary. Place in the refrigerator for 30 minutes.

- Cut the beef into ½ cm (1/4 inch) slices.

- Heat a little oil in a large frying pan and fry the meat over a medium heat until cooked through, 3-4 minutes on each side.

- Transfer the meat to a plate, cover with foil and leave for 10 minutes. Then chop into small pieces.

- Cut the onions into small cubes. Heat half the oil in a frying pan, add the onion and sauté over medium heat until golden.

- Peel pickles, cut in half, remove the seeds. Chop the flesh very finely.

- Mix meat, onions, pickles; add the remaining melted butter and brine, salt and pepper to taste.

- Heat the oven to 200°C / 390°F.

- Divide the dough into 14-16 pieces.

- Roll out each piece into a circle, place the filling and pinch. Baste the pies with whipped egg yolk mixed with water or milk.

- Bake in a preheated oven for 30-40 minutes. Let the patties rest for 10-15 minutes before serving.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office has designated The Moscow Times as an “undesirable” organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a “foreign agent.”

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work “discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership.” We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you’re defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.