How to Ward Off Vampires and Foreigners: Garlic

Garlic is the best way to keep vampires away, as everyone knows. Russia has never had much trouble with vampires, although it has plenty evil of its own kind. But garlic is a welcome ingredient in our historical cuisine.

Many foreigners who visit Russia are perplexed by certain aspects of our traditional cuisine, such as sprinkling dill on virtually every dish. But a few centuries ago, foreigners were perplexed by something else: the taste and smell of garlic in many Russian dishes.

As Professor Gavriil Uspensky of Kharkiv University wrote in a review of Russian cuisine in 1818, foreigners visiting Moscow in the Middle Ages “praised our drinks much more than our food.”

Foreigners were deeply impressed by the abundance of natural riches: fish, vegetables, wild game. But they couldn’t understand Russian cuisine. “Either out of choice or perhaps insufficient knowledge of the art of cookery, all these treasures were greatly neglected. German, French and English travelers found it especially strange that Russians were disgusted by what the foreign visitors considered many tasty and healthy viands, that they ate more fish than meat and garden greens, that they preferred salted and smoked meat to fresh meat and half-raw meat to skillfully prepared meat, that they preferred cold food above all and that they seasoned all their dishes excessively with garlic and onions, or salt, pepper and vinegar.”

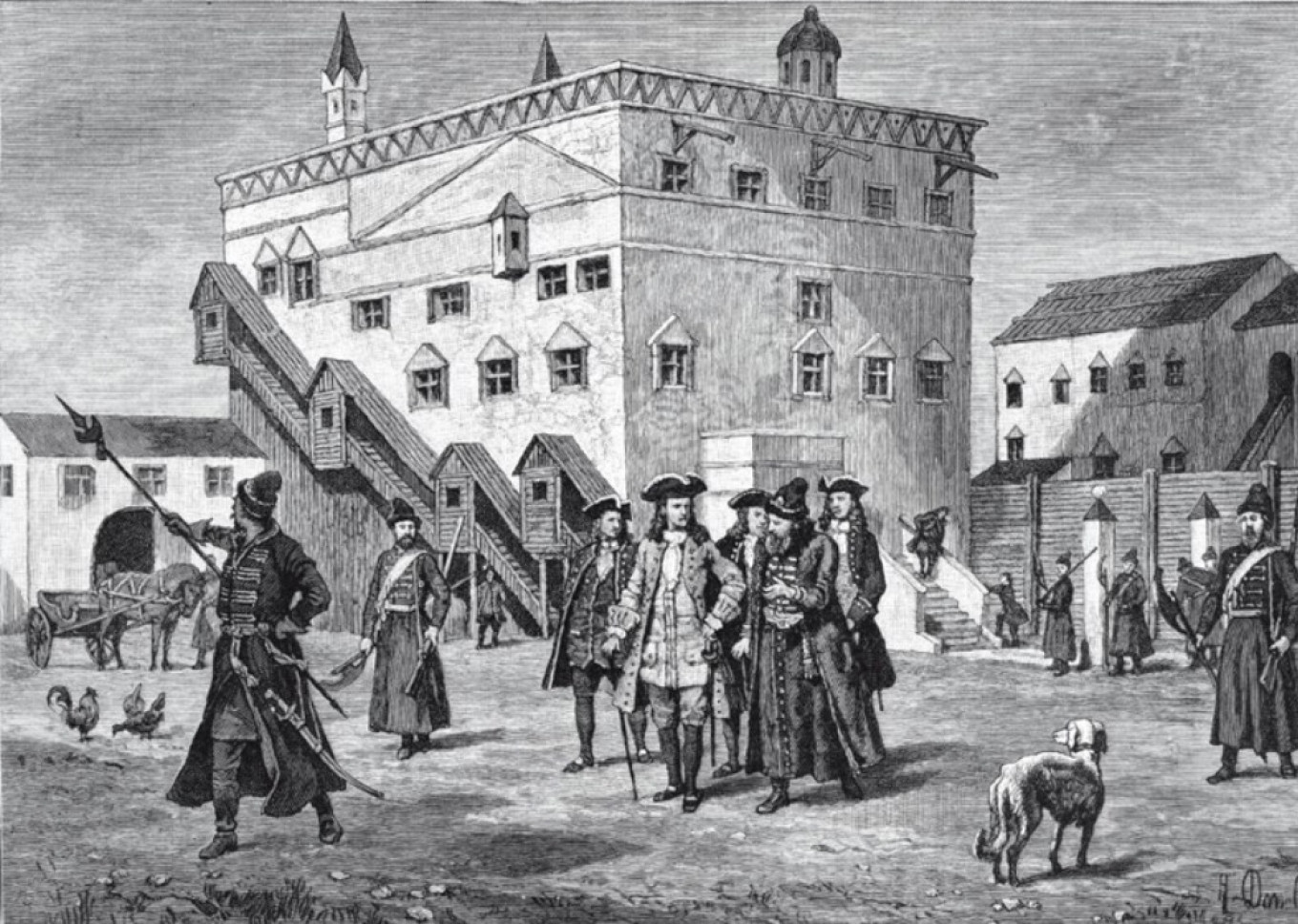

Wikimedia Commons

However, along with the problem of the usual “difference of tastes” there is another issue at hand here. In those years people preserved food differently in Europe and in Russia. In the West people used herbs and spices from Asia and Africa; in Russia the natural preservatives were onions, garlic and salt.

“To some extent, our cuisine is characterized by pies, which from antiquity were divided into podovye (baked “on podu” — on the bottom of the oven) made of leavened dough, and “buckled” pies (fried in oil), sometimes made of unleavened dough. Food was not salted during preparation, so everyone salted food to their taste at the table,” a culinary researcher wrote in 1902. Various seasonings were used, especially onions, garlic and saffron.

Onions and garlic were even included in the salaries given to many Moscow officials. Horseradish and dill were also commonly used in large quantities, as well as parsley, anise, coriander, bay leaf, black pepper and cloves, which had appeared in Russia by the 12th century. In the 15th and early 16th century they were supplemented by ginger, cardamom and cinnamon.

“The nobles eat a little better, but they use little seasoning for dishes except garlic and onions,” wrote Jiří David, a Czech Catholic priest and author of the treatise “The Present State of Great Russia or Muscovy” (1690). “Some, however, are already imitating how foreigners eat. Their custom after dinner is to sleep a little and rest. Historians tell us that Tsar Dmitry (whom they consider an impostor) was under suspicion and not considered for a true Muscovite because he did not sleep after a meal.”

In Muscovy during those years dishes were usually cooked with garlic and onions. Foreigners wrote that all rooms and houses, including the magnificent chambers of the Grand Duke’s palace in the Kremlin, as well as any place they even stopped in for a quick visit, were impregnated with an odor “repugnant to foreigners.” This was indeed a serious problem for foreign visitors. Many European envoys had a difficult time finding something edible among the dozens of dishes sent to them by the Tsar. “They were disgusted by the strong odor and taste of garlic and onion, or the nasty smell of hemp or badly prepared butter that they used in making all the dishes made with flour, all the pies and fried fish,” wrote Gavriil Uspensky.

Wikimedia Commons

Foy de la Neufville, the Polish ambassador to the Moscow court in 1689 wrote with light humor: “The Tsar sent me a dinner from his table that consisted of a 40-pound piece of smoked beef, several fish dishes fried in walnut oil, half a piglet, a dozen half-fried pies with meat, garlic and saffron, and three large bottles of vodka, Spanish wine and honey. In answering the question of how I found the dinner sent to me by the Tsar, I had to note that, unfortunately for me, French cooks have so spoiled my taste that I can no longer appreciate other cuisines, as testified by the fact that I have long missed French ragu.”

Wikimedia Commons

But another foreigner, Sir Thomas Smith, who visited Moscow as a member of the English embassy in 1604, spoke about the local food in very enthusiastic terms. Of course, this reflects the well-known contradiction between the French and English world views. The sophistication of French cuisine even then was very different from the restrained aristocratic English cuisine. And indeed, English travelers were well known for their willingness to eat other cuisines, whether in ancient Russia, India or Africa.

One conclusion can be drawn from all this. Russian cuisine in those years was not greatly different from European cuisine — with the possible exception of the abundance of garlic and onions. It seems to have been in keeping with the average culinary customs of those years. Some foreigners liked it, some did not. It is clear that devotees of French cooking, which had made a dramatic leap in the previous decades, regarded Russian cuisine as quite backward. But, on the other hand, the same could be said about the culinary cultures of most European countries of that time. This was normal — nothing but a matter of taste, as they say.

Instead of preparing a recipe for those years, we have one of our favorite dishes made with garlic. Garlic and herbs go brilliantly together, and these bright colors will bring the long-awaited summer closer.

Herb and Garlic Stuffed Tomatoes

Ingredients

- 10 small tomatoes

- 1 bunch cilantro

- 1 bunch parsley

- 1 bunch dill

- 1 small hot pepper

- 3-4 cloves of garlic

- 1 tsp sugar

- salt, pepper to taste

- 1 Tbsp white wine vinegar

- 1 Tbsp vegetable oil

Instructions

- Take 10 small tomatoes with dense flesh, wash them thoroughly, cut off a small cap around the stem. Use a teaspoon to scrape out the entire center, being careful not to damage the sides. Turn over with the cut side down and place on a plate to let all the juice drain off.

- Wash and dry the herbs, chop finely, mix with chopped garlic and pepper. Add the salt, sugar, pepper, vinegar and oil. Mix well and fill the tomatoes.

What else can be tomatoes be filled with? There are many options, such as:

- finely chopped celery and apples dressed with sour cream, salt and pepper

- boiled shrimp with apples, celery, walnuts and mayonnaise

- diced boiled potatoes, carrots, celery, apples, pickles and green peas

- finely chopped bryndza (or feta), olives, cucumber, sweet pepper and garlic dressed with olive oil.

All stuffed tomatoes should be served only after they “rest” for 1 hour in the refrigerator to soak up the flavors of the filling.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia’s Prosecutor General’s Office has designated The Moscow Times as an “undesirable” organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a “foreign agent.”

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work “discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership.” We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you’re defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Continue

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.