Chinese firms, anxious to avoid choppy geopolitical waters, chart a course for Vietnam

[ad_1]

“They told me to go outside,” he recalled. “It’s their suggestion of relocating to a country with lower costs.”

Quarrels like these are common for Chinese exporters amid protracted trade tensions with the United States and an exodus of manufacturers to cheaper locales like Vietnam.

Ying has supplied a majority of his products to American barbershops and beauty parlours for years through his two factories in China.

But many of his entrepreneur friends have already moved, in whole or in part, to Vietnam. Tariffs had taken a heavy toll on their profits and threatened to drive them out of the business.

Chinese factories that are manufacturing for these US firms … are going to have to follow their customers

“I may go there someday,” said Ying, who paid two visits to Haiphong last year. The Vietnamese coastal city is already packed with factories backed by Chinese investment.

Vietnam is often the first choice when Chinese manufacturers consider relocating overseas, because the country has a large working population and easier access to developed markets.

“Vietnam is an important locality for firms that want a China+1 strategy,” said David Zweig, professor emeritus with the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

“Chinese factories that are manufacturing for these US firms and then shipping the goods to the US are going to have to follow their customers and go to Vietnam.”

“Moving to Vietnam or elsewhere in [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] may become inevitable,” he said.

Vietnam is a member of two major US-led trade agreements, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Chinese firms poured US$2.92 billion in direct investments into the country for the first nine months of 2023, nearly doubling the amount from the previous year according to Vietnam’s Ministry of Planning and Investment.

The world’s top exporter saw outbound shipments dip 5.2 per cent year on year to US$3.07 trillion in the first 11 months of last year, with exports to the US and European Union slumping by 13.8 per cent and 11 per cent, respectively.

Changing laws and regulations … worry non-local firms … In Vietnam, [they] may face risks

The impact is reverberating across coastal provinces like Guangdong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang, where purchases from the West are a source of considerable income.

These regions are seeing some of their production migrate to countries like Vietnam, as rising costs at home and geopolitical tensions have become major “push factors.”

Relocation, however, is no guarantee of success.

“Changing laws and regulations with clauses not clearly defined, as well as issues like national security and data security, usually worry non-local firms,” the researcher said.

In Vietnam, foreign firms may face risks as the country introduces laws on intellectual property, competition and data management.”

“The revised Cybersecurity Law mandates all foreign entities to store and host data in Vietnam, which may increase costs and compliance risks,” Yang added.

Yang urged Chinese investors to carefully study Vietnam’s complex tax, land use and labour laws before making the plunge.

“Exporters not troubled by US tariffs should see Vietnam as just one of many expansion options.”

Tjia Yin Nor, an associate professor with City University of Hong Kong’s Department of Public and International Affairs, said one issue of note is labour law compliance.

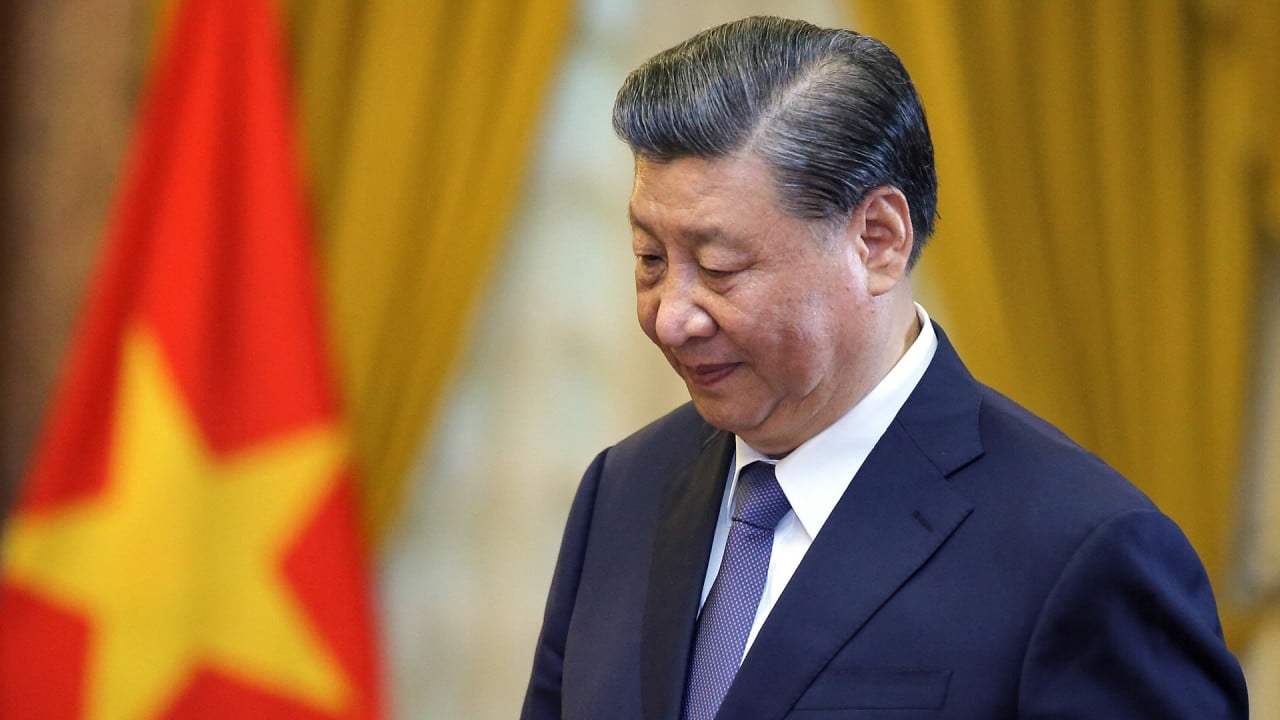

Amid global supply chain shifts, China eyes Vietnam for ‘strategic’ cooperation

Amid global supply chain shifts, China eyes Vietnam for ‘strategic’ cooperation

“Chinese companies tend to employ interns in Vietnam, but this practice has been criticised. Some firms, unfamiliar with local laws, face charges of youth exploitation,” she said.

There have been reports, Yang said, of Chinese workers on business visas being fined or deported after raids where local enforcers found them working without a permit.

In 2022, Beijing’s embassy in Hanoi issued a reminder to those doing business in Vietnam to abide by local employment laws.

Overall costs have also soared.

We’re trapped in losses in Vietnam … If there’s no turnaround this year, we may pull up stakes and return

Zhou Libin, a manager of Tiansu Machinery and Technology from east China’s Zhejiang province, said the monthly salary of a skilled worker in Haiphong was 1,000 yuan (US$140) in 2018, the year when then-US president Donald Trump launched the trade war. But that has since tripled.

The average daily rent for a plant in Haiphong runs from 1 yuan to 1.5 yuan per square metre, almost identical to many industrial estates in Zhejiang with better infrastructure – and before the cost of shipping intermediate goods from China is factored in.

“We’re trapped in losses in Vietnam … If there’s no turnaround this year, we may pull up stakes and return,” Zhou said.

He lamented that today’s Vietnam is radically different from what it was just six years ago.

“Yes, exporting to the US is easier [from Vietnam] but we are barely making profit,” he said.

“Everything is getting more expensive, to the point you wonder if it would be better to produce back home.” This is not just talk – he shifted some of his production back last year.

Small players are not the only ones who are beating a retreat.

In November, Texhong International, one of China’s largest textile producers, sold its 250,000-square-metre (2.7-million-sq-ft) plant in Vietnam’s Quang Ninh province, a major setback for the firm’s operations, which began in 2006.

The Shanghai-based company said in its exchange filings the move was part of a larger disposal of loss-making operations.

Both Chinese and Vietnamese manufacturers should … avoid the unfavourable side of big power competition

But Beijing still views Hanoi as a preferred gateway, as the existing US tariff structure on Chinese products remains intact and more – encompassing commodities, services and technologies – could be adjusted in the future.

“Both countries will encourage and support enterprises with strength, credibility and advanced technologies to invest and will create a fair, convenient environment,” the document read.

China’s southern neighbour is its biggest trading partner in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

“Vietnam’s export substitution economy has a need to draw Chinese manufacturers to its economy,” said Ha Hoang Hop, an associate senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore.

“Both Chinese and Vietnamese manufacturers should leverage the momentum [from Xi’s visit], and avoid the unfavourable side of big power competition.”

Many provinces provide subsidies to local firms, including those specialising in consumer goods, home appliances and photovoltaic cells, to incentivise expansion into participating countries.

Zhejiang is one such region. According to a report from local state media outlet Zhejiang Daily, the province hoped to emulate the overseas expansion of Korean and Japanese companies by using investments abroad to benefit the domestic economy while preventing the hollowing out of indigenous industry.

The report quoted Oscar Liu with Powernice Intelligent Technology, a producer of photovoltaic panel and cell components that runs a plant in Vietnam.

Liu, a partner, said expanding overseas did not mean the company had given up on the domestic market.

“We hope the government can help when we bring overseas profits and experience back to China, to plough our overseas earnings into innovation and upgrades at home,” Liu said.

[ad_2]

Source link