Indonesia election 2024: will Anies and Ganjar join hands to deny Prabowo an outright victory?

[ad_1]

“Half of our soldiers do not have official residences, while the minister owns 340,000 hectares of land,” said Anies, who claimed he was citing the same data used by Widodo when he faced off with Prabowo in the 2019 election.

Prabowo appeared disgruntled at the end of Sunday’s debate, saying: “I was a little disappointed by the quality [of the debate], especially the narratives that were conveyed by the other candidates.”

Ian Wilson, a senior fellow at the Indo-Pacific Research Centre at Murdoch University, said Anies and Ganjar ganging up on the front runner was to be expected.

“Prabowo is largely seen as the one to beat by both candidates because of his position in the polls, so you can see why they would be taking aim at him,” he said.

From India to Indonesia, 2024 is Asia’s election year. But will anything change?

From India to Indonesia, 2024 is Asia’s election year. But will anything change?

The priority for the other two candidates was to create a scenario where the election goes into a run-off, he added.

If no single candidate receives more than half the votes on February 14, the electoral battle will be pushed by more than four months to a second round run-off between the first- and second-place finishers on June 26.

“I don’t think Prabowo has the votes to win outright in the first round, so we can expect to see a second round,” Wilson said. “There are still big blocks of people who are undecided, and so, as we have seen in previous elections, a lot will rest on how things play out on election day.”

Shifting perceptions

Anies, as the sole opposition candidate, has perhaps benefited the most from the televised contests, according to observers.

His strategy to attack Prabowo appears to have paid off. From last place, Anies has catapulted himself to a neck-and-neck race with Ganjar, even surpassing the ruling party’s pick in some polls.

An opinion poll by Indikator Politik published on January 6 showed Prabowo leading with 46.9 per cent, Anies at second place with 23.2 per cent and Ganjar taking the last spot with 22.2 per cent.

“Support for Anies has increased because he’s presenting himself as a real opposition candidate, while Ganjar seems to be a bit more inconsistent and stuck in the middle,” said Yohanes Sulaiman, a politics and security analyst at the Jenderal Achmad Yani University in Bandung, Indonesia.

What policies are Indonesia’s 3 presidential hopefuls pushing?

What policies are Indonesia’s 3 presidential hopefuls pushing?

Ganjar had initially been seen as a front runner given he belongs to the same party as Widodo, leading to expectations the highly popular president would back the candidate from his Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P).

“Ganjar seems to have a bit of an existential problem,” Wilson said. “Is he an oppositional candidate, or is he the guy who is going to continue Jokowi’s policies?”

There is also Ganjar’s perceived association with PDI-P chairwoman Megawati Soekarnoputri, which risks alienating a substantial portion of the electorate, according to Yohanes, with concerns that she may overshadow Ganjar if he assumes a position of power.

But with election day only a month away, changing the public’s perception of Ganjar will only become more difficult, observers say.

“You do hear that there is some unease from the PDI-P that things are not going as planned, and perhaps the party machine has not delivered the way that it had hoped in terms of getting support for Ganjar,” Wilson said.

Prabowo’s to lose?

The presidential debates have a significant impact on a candidate’s ability to attract undecided voters, according to Wasisto Raharjo Jati, a political analyst with the Jakarta-based National Research and Innovation Agency.

“This is where they can impress the swing voters, and this is particularly important for Anies and Ganjar,” he said.

Despite his popularity, support for Prabowo appears to have stagnated, which might be a cause for concern for his camp, Yohanes said.

“You can see in the debates that Prabowo is trying to play it safe, just trying to survive the rounds and not make too many attacks at Ganjar, because those are the voters he will most likely want to attract to his side,” he added.

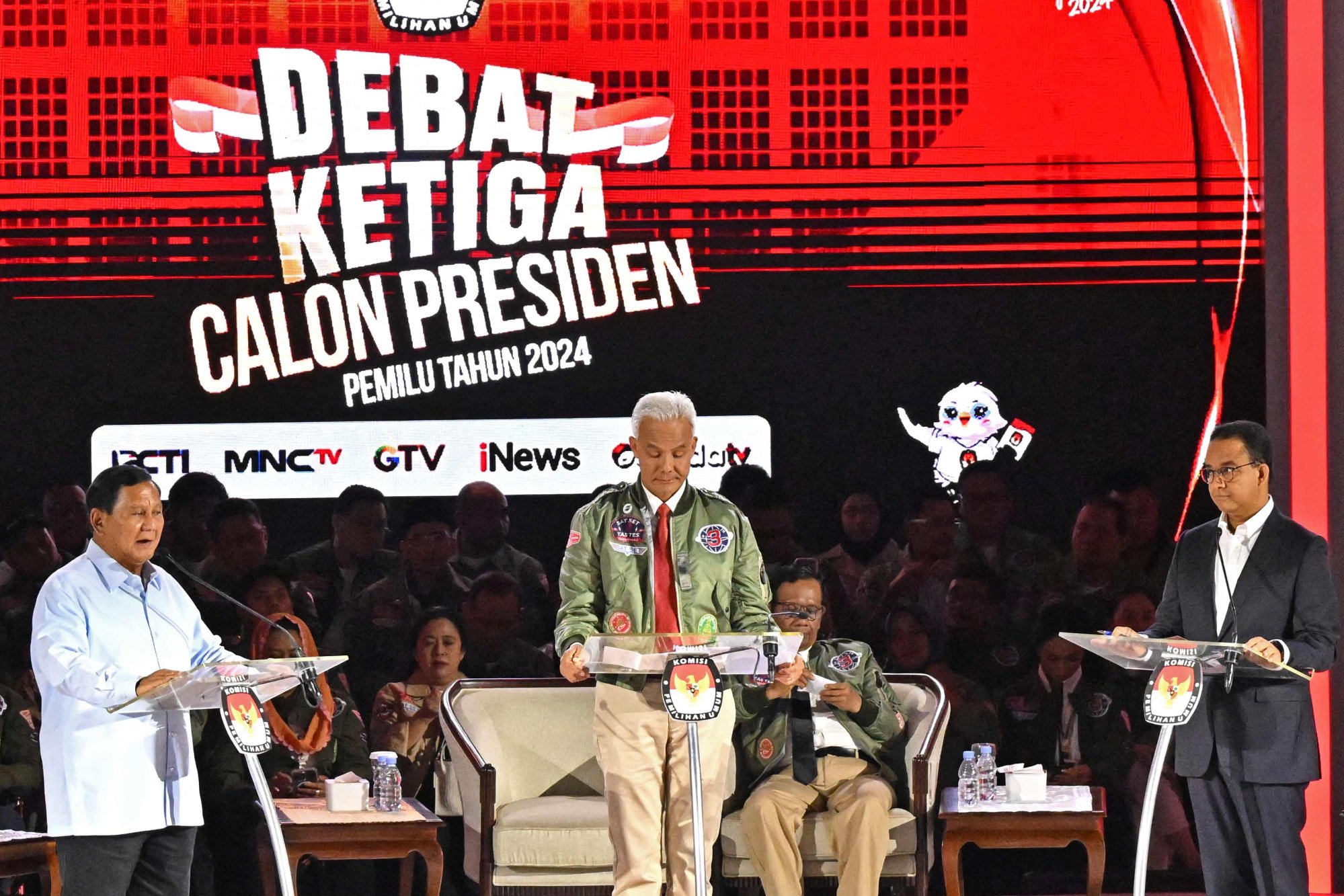

Defensive Prabowo ‘underwhelms’ in third Indonesia debate as rivals go on attack

Defensive Prabowo ‘underwhelms’ in third Indonesia debate as rivals go on attack

Anies and Ganjar’s probing attacks might also be an effort to provoke Prabowo, Wilson said.

In recent years, the former general has made efforts to transform his strongman image into that of a statesman, adopting a softer and more diplomatic approach.

“Prabowo can lose his cool; he has had a reputation where he can be volatile, and I think [the other candidates] might want to bring that out for the voters to see,” Wilson said.

Only time will tell what other tactics Ganjar and Anies might employ to change their electoral fortunes in this last month.

One idea that has been floated is that they may form an alliance to deny Prabowo an outright win and force a run-off. However, analysts think the odds of this are remote, given that cooperation between Ganjar’s secular PDI-P and Anies – whose Coalition of Change for Unity includes the Islamist, conservative Prosperous Justice Party – would be challenging.

However, Indonesian politics can make strange bedfellows. After all, virtually nobody could have predicted in 2019 that Widodo would later tap his fiercest electoral rival to become his defence minister, much less that Prabowo’s next running mate would be the president’s son. So it might be prudent to continue to expect the unexpected.

[ad_2]

Source link