The Indian Ocean has been receiving considerable attention recently, with a conclave of naval chiefs of littoral nations meeting in Bangkok under the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium banner. The symposium is an Indian initiative begun in 2008 and seeks to further maritime cooperation among the regional navies of the Indian Ocean.

Earlier, China convened a maritime conference in Kunming to enhance blue-economy cooperation with select Indian Ocean nations under the theme of “Boosting Sustainable Blue Economy to Build Together a Maritime Community with a Shared Future”. Organised by China’s

International Development Cooperation Agency, the geopolitical subtext of the conference was visible in different ways.

The Indian Ocean region was referred to as the “China-Indian Ocean Region”, perhaps to avoid identifying the ocean with India. Furthermore, India was not among the invited nations. This is indicative of the brittleness of the relationship between the two Asian giants.

The agreements arrived at in Kunming are unremarkable and seek to foster greater cooperation between China and the smaller Indian Ocean region littoral nations. Four sub-forums were held to address cooperation in the blue economy, cooperation in maritime disaster prevention and reduction, biodiversity and maritime ecology protection, and sustainable development of the island countries of the Indian Ocean.

The Maldives – an archipelago in the southwestern Indian Ocean with a population of less than 600,000 people and a total land area of less than 300 square kilometres – has emerged from the ranks of smaller islands nations as a symbol of China-India competition in the region. Traditionally seen as benefiting from close cooperation with India,

a tightly contested election in September resulted in a China-friendly party taking power in Male.

Hussain Mohamed Latheef, the newly appointed vice-president of the Maldives, was among those invited to Kunming and said, “The president and the government is committed to strengthen the ties with China that have been long-standing and built upon the foundation of mutual respect and shared goals.” He said Beijing had played “a pivotal role” in the development of the island nation in recent decades.

This endorsement of China came after new Maldivian President Mohamed Muizzu

called for an end to India’s limited military presence in his country. Since gaining independence from Britain in 1965, the Maldives has had a close relationship with India; New Delhi has been a first responder to crises in the Maldives.

Against this backdrop, it is instructive that the Maldives attended the Kunming conference for the first time after the previous government chose not to attend the

inaugural edition in 2022. It is also significant that the new Maldives government doesn’t appear to have sent a national security adviser-level representative to the

Colombo Security Conclave, which took place at the same time in Port Louis, Mauritius.

The conclave is an Indian Ocean forum that brings together the national security advisers of India, the Maldives, Sri Lanka and Mauritius. From an Indian perspective, it is troubling that the Maldives has adopted

an anti-India posture, as this could harm Indian security interests.

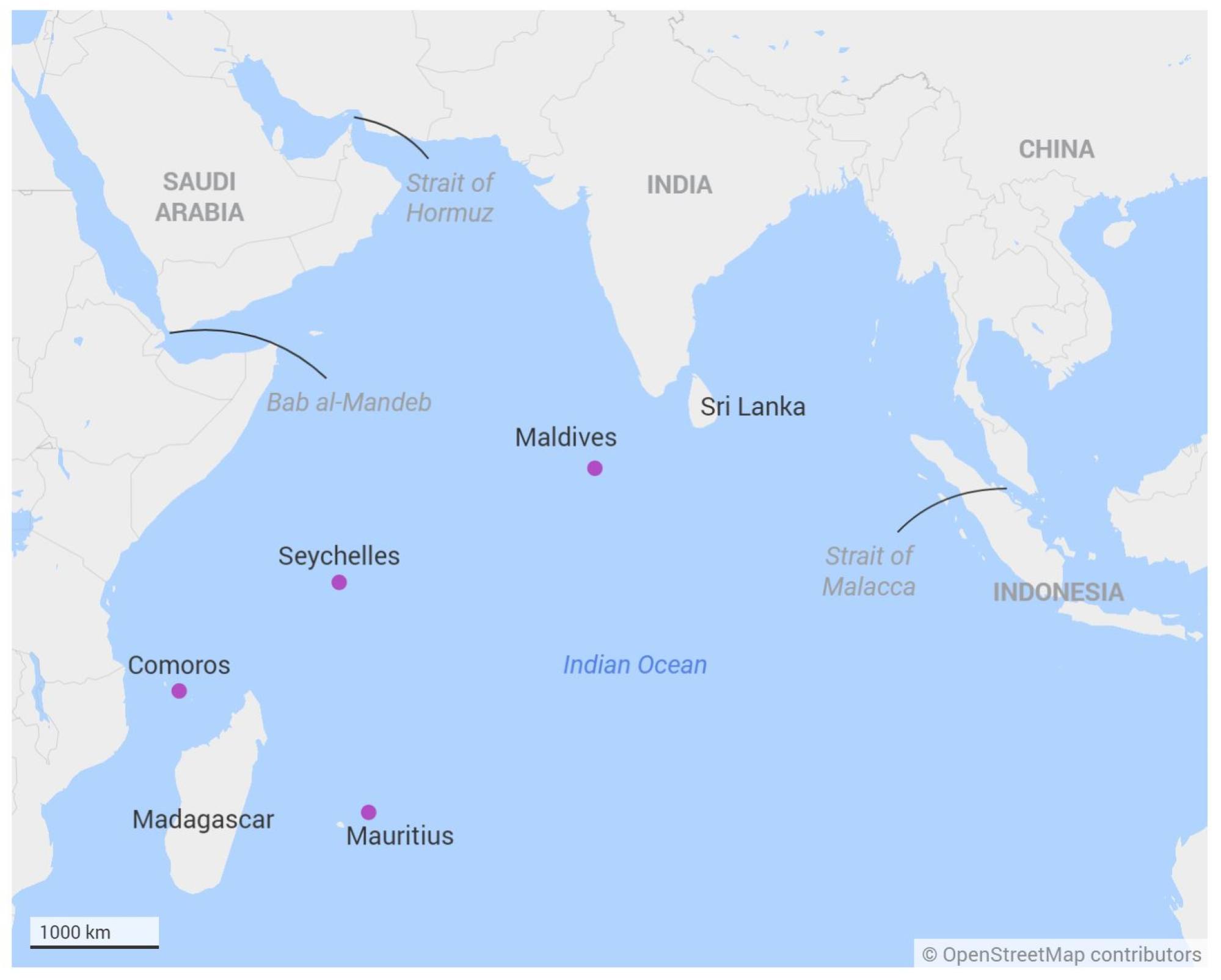

Given its constrained maritime geography, the geopolitics of the western Pacific and its profile as a major economy dependent on trade and energy flows, China has long resolved to secure access to the Indian Ocean. Its vast trade and energy supplies depend on the stability of its sea lanes. When China became a net importer of energy earlier this century, it voiced its concern about the “

Malacca dilemma” and its vulnerability in this maritime domain.

As a result, China has sought to enlarge its regional footprint over the years, with the Gwadar port in Pakistan one of many important investments. In a similar fashion, China-built ports in

Sri Lanka and

Myanmar are part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative and are also viewed as being encompassed by its “

string of pearls” maritime strategy.

China’s naval presence in the Indian Ocean region has grown steadily – from the Chinese navy joining

anti-piracy patrols off Somalia in 2009 to being a near-permanent feature of Beijing’s military outreach, which includes its first

overseas military base in Djibouti. China is now a credible regional presence whose power is likely to consolidate in ways that will irk India.

Bringing the Maldives into a closer relationship is a major feather in the cap for China, the more so when this has been done at the expense of India.

One tenet of maritime strategy is that distant bases can overcome the constraints of geography and act as launching pads

for military initiatives, which can be seen in the investments major powers have made in the oceans of the world over centuries. As such, the strategic significance of certain small island states in the Indian Ocean Region – with their being near critical sea lanes and choke points – is being burnished. The Maldives is now a symbol of China-India competition in the maritime domain.

Pitting major states against each other can benefit small island states, but the real challenge for major powers will be dealing with exigencies that go beyond hard security issues. If global warming

leads to rising sea levels, the Maldives could be among the first nations to submerge, creating a new climate refugee crisis. Do Beijing and Delhi have the intent and ability to create an appropriate response?

While China and India remain hostage to their geopolitical insecurities, the maritime domain is fraught with complex challenges that call for collaborative efforts among major powers. Whether the current political leadership can rise to the occasion is debatable.

Commodore C. Uday Bhaskar is director of the Society for Policy Studies (SPS), an independent think tank based in New Delhi