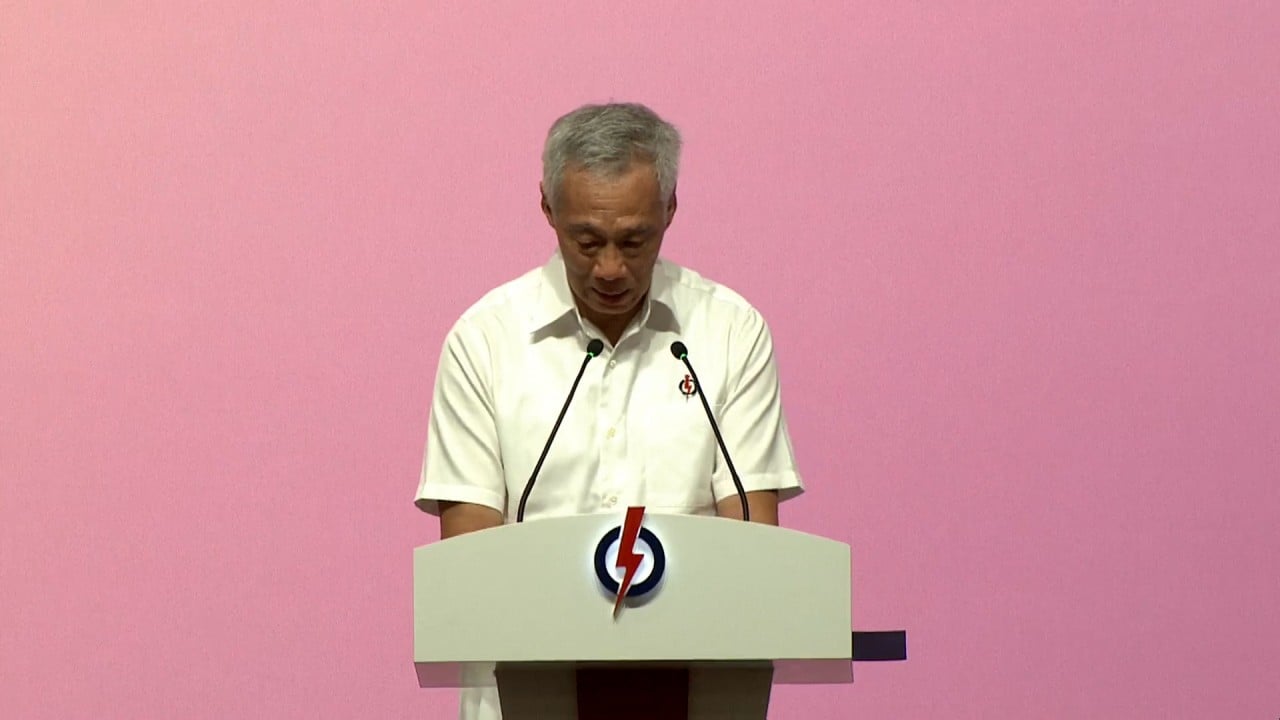

Singapore’s ruling PAP is ‘winning’ at social media, but does it translate into votes?

[ad_1]

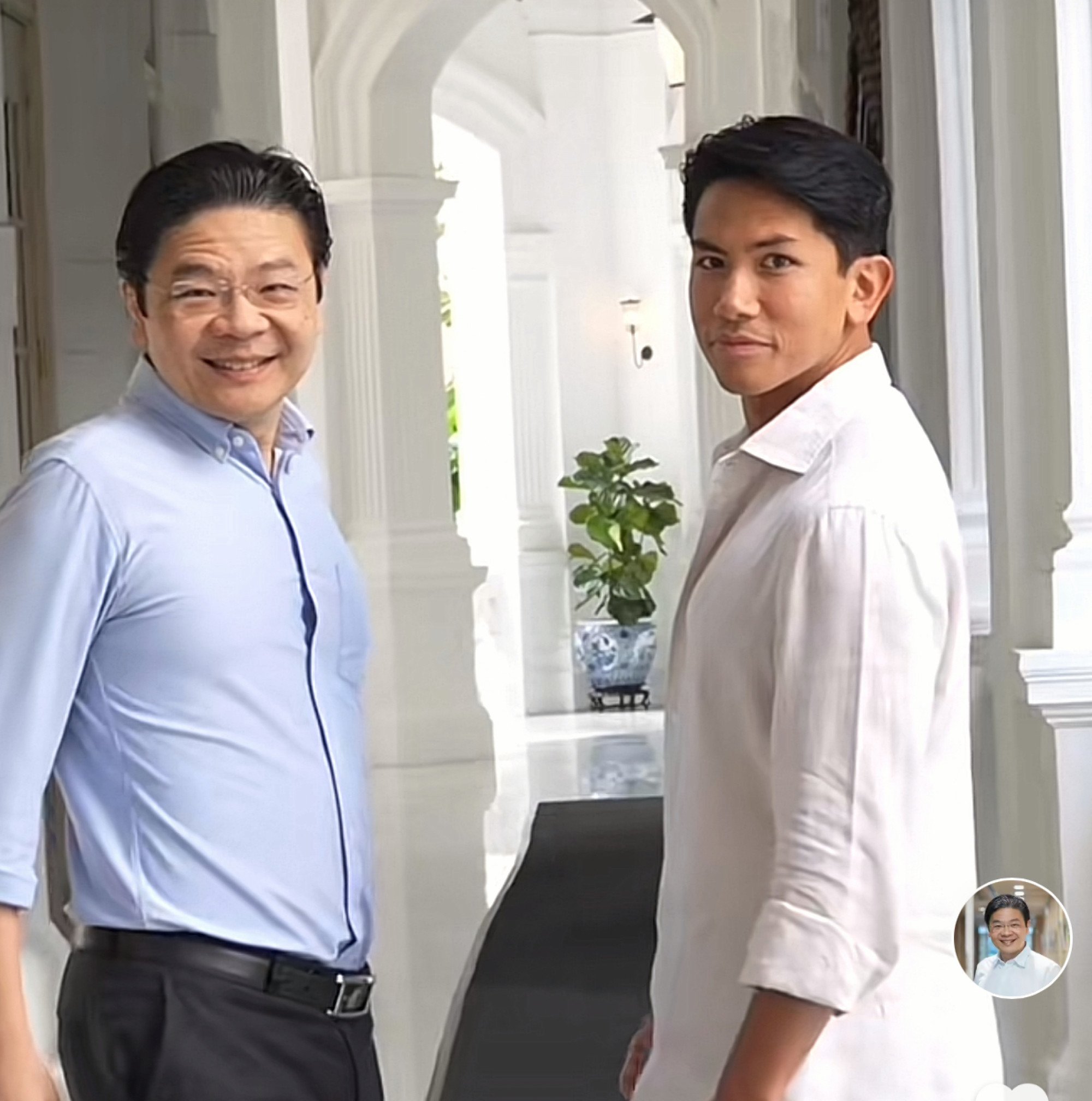

“Now that’s how you build relations … with style,” one user wrote.

“Lawrence Wong thirst-trapping us,” another said, using slang to suggest sex appeal.

Political observers say the trends showed the PAP has cracked the youth code, but critics, citing concerns about sponsored social media campaigns that are not entirely transparent, argue the ruling party’s ability to splurge gave it an outsized advantage over its political opponents.

When the shift towards Web 2.0 began to gain momentum in Singapore in the early 2000s, many saw the internet and social media as a haven for dissenting views and critical opinions of the Singapore government amid a highly regulated media landscape.

Now, with money to splash on advertisements, a strong social media strategy, and collaborations with meme pages and influencers who boast hundreds and thousands of followers, the government’s influence on the digital sphere has become far-reaching.

I see this approach as an effort to communicate with a broader audience, especially the younger segment, in a medium that resonates with them

“Some ministers like DPM Lawrence Wong and Minister Ong Ye Kung have been winning at social media. They … have shown that they are on the pulse and can create a variety of content on social media that is educational, humorous and relatable,” said Joel Lim, managing director of digital media firm Zyrup Media, and the host of Political Prude: The Podcast.

These clips of ministers strumming their guitars or working out in tank tops are no different from traditional walkabouts in hawker centres, he noted.

“By embracing the format, they can present themselves to be more relatable and appear more accessible. I see this approach as essentially an effort to communicate with a broader audience, especially the younger segment, in a medium that resonates with them,” Lim said.

As alternative blogs that once drew a sizeable readership nearly two decades ago waned in popularity, some opposition politicians have picked up on the new rules of engagement on social media.

In the last general election in 2020, Tan Cheng Bock, 83, chairman of the opposition Progress Singapore Party, earned himself the affectionate nickname of “Hypebeast ah gong”, meaning trendy grandpa, after he documented himself attempting to use internet slang.

Aside from Tan, while Singapore’s opposition parties have TikTok accounts, most videos are policy-related rather than personality-driven – showing snippets of parliamentary speeches and policy proposals – garnering much less attention compared with the PAP.

The government is also one of the biggest advertisers in the country, with the Ministry of Communications as the third-largest spender in the first half of 2022, according to Nielsen, a data and market measurement firm.

In 2019, the Ministry for Communications and Information estimated that the government spent between S$150 million (US$112.9 million) and S$175 million on advertising, with the amount increasing by 30-50 per cent in 2020 and 2021, due to Covid-related announcements.

Painting Singapore’s ruling party politicians in an unfavourable light or contradicting the government could cause emerging platforms to lose out on “lucrative” sponsorships or advertising deals, said Australia-based communications lecturer Howard Lee of Murdoch University.

“In a country where the government controls most of the economic levers, you either get goodwill funding from opposition supporters and starve, or get lucrative funding from the government, prosper and be labelled a PAP lapdog,” Lee said.

Other commentators say this gives ruling-party politicians a significant advantage in social media. “Given the PAP’s resources, this does mean that they can produce content in a much more polished manner and can use other accounts – like ministry accounts – to put forward information such as new policies or just increase the visibility of their members,” said Rebecca Grace Tan, a political-science lecturer at the National University of Singapore.

During a parliamentary session earlier this year, an opposition politician called for greater transparency on political advertisements, suggesting that local social media page SGAG had attempted to conceal that its posts were sponsored by the government.

More recently, podcast The Daily Ketchup became the latest subject of scrutiny among netizens – with many questioning whether these episodes, which regularly host ministers as guests, had been sponsored.

This Week in Asia contacted The Daily Ketchup’s team for a comment but did not receive a response.

‘Singapore Dream’ is a life filled with meaning and purpose, No 2 leader says

‘Singapore Dream’ is a life filled with meaning and purpose, No 2 leader says

Many social media appearances by politicians have been directed at “image softening”, to appear more authentic and relatable to audiences, which analysts and industry observers said helps political officeholders move past the public’s long-held perception of their elitism.

Consistent social media engagement could turn a number of these Gen Z viewers, who have yet to form any sort of party loyalty, into supporters by the next general election, said Tracy Loh, senior lecturer of communication management at the Singapore Management University.

“To a certain extent, voting is a function of familiarity. When you go to the ballot box and … if you can’t put the name and the face together, you’re not going to vote for that person,” she said.

Personalisation is “particularly significant for the PAP”, said Tan from NUS, adding that clips humanising them could counter the perception that its politicians were out of touch.

But an over-fixation on personality politics instead of policy issues and a user-driven intolerance towards discourse could see “the impoverishment of our political space for logical debate”, Lee warned.

“It does present a problem when voters see personality as the defining characteristic of politicians, rather than emphasise evaluating their real competence,” he said.

While consistent digital engagement with politicians may make them appear “more credible and trustable”, there was more that went into the decision behind a vote, said Natalie Pang, an associate professor at NUS’ communications and new media department.

“This will matter when the MPs and ministers start putting out more ‘serious’ content about issues or policies. It can translate into votes, but as studies of voting behaviour have shown, it will not be the only reason influencing how one votes,” she said.

Tan also highlights that many non-party political news outlets have entered the scene in recent years, such as Jom and Wake Up Singapore, and podcasts like Teh Tarik with Walid.

“This might counter some of the concerns about polarisation and superficiality. But once again, it depends on whether it is being used in good faith.”

[ad_2]

Source link