South China Sea: Philippines risks its Beijing ties with ‘non-starter’ mini code of conduct plan

[ad_1]

Ganging up a ‘non-starter’

Storey said Manila’s suggestion for separate talks stemmed from these increased tensions and its frustration at the slow pace of COC talks with Beijing.

“But it’s a non-starter. China would absolutely reject it. Beijing won’t sign any agreement it wasn’t involved in the negotiations for from the beginning,” he said.

“It would also see it as an attempt by the Southeast Asian claimants to ‘gang up’ on it.”

The collapse of the COC process [with Beijing] could be disastrous for Asean, which is already beset with a host of problems

“Beijing’s motivation for having a COC with Asean differs from the bloc’s anyway,” Koh said, noting that China needed the code to demonstrate that regional disputes could be addressed amicably by the concerned parties without extra-regional interference.

“Asean needs the code to assert its relevance and centrality” he said, pointing out that if talks collapsed, Beijing could blame it on parties involved in the “mini COC”.

“However, the collapse of the COC process could be disastrous for Asean, which is already beset with a host of problems that call into question its claims of relevance and centrality,” Koh said.

China has been able to exploit this consensus-based model, which allows any of the 10 member states that dissents to veto decision-making processes, in its COC negotiations with Asean, according to analysts Tanvi Kulkarni, Frank O’Donnell, Shatabhisha Shetty and Angela Woodward.

“Disagreements persist over the geographical scope of the code, the scope of permissible maritime activities, measures to manage escalation of disputes and promote self-restraint, the roles of different regional powers, and the issue of whether the code should be legally binding or otherwise,” they wrote in their report Tackling Maritime Incidents and Escalation in the Asia-Pacific, published on Thursday by the Seoul-based Asia-Pacific Leadership Network.

But better than ‘standing still’?

While China would likely react negatively to any “mini COC”, Joshua Bernard Espeña, a defence analyst and resident fellow at the International Development and Security Cooperation think tank in Manila, argued that such a pact would be better than “standing still” and could help sort out lingering issues between other claimant states.

“This involves providing diplomatic support, engaging in freedom of navigation operations, and making economic contributions,” Espeña said, noting that without such backing, “China’s hegemonic actions” could scuttle the pact.

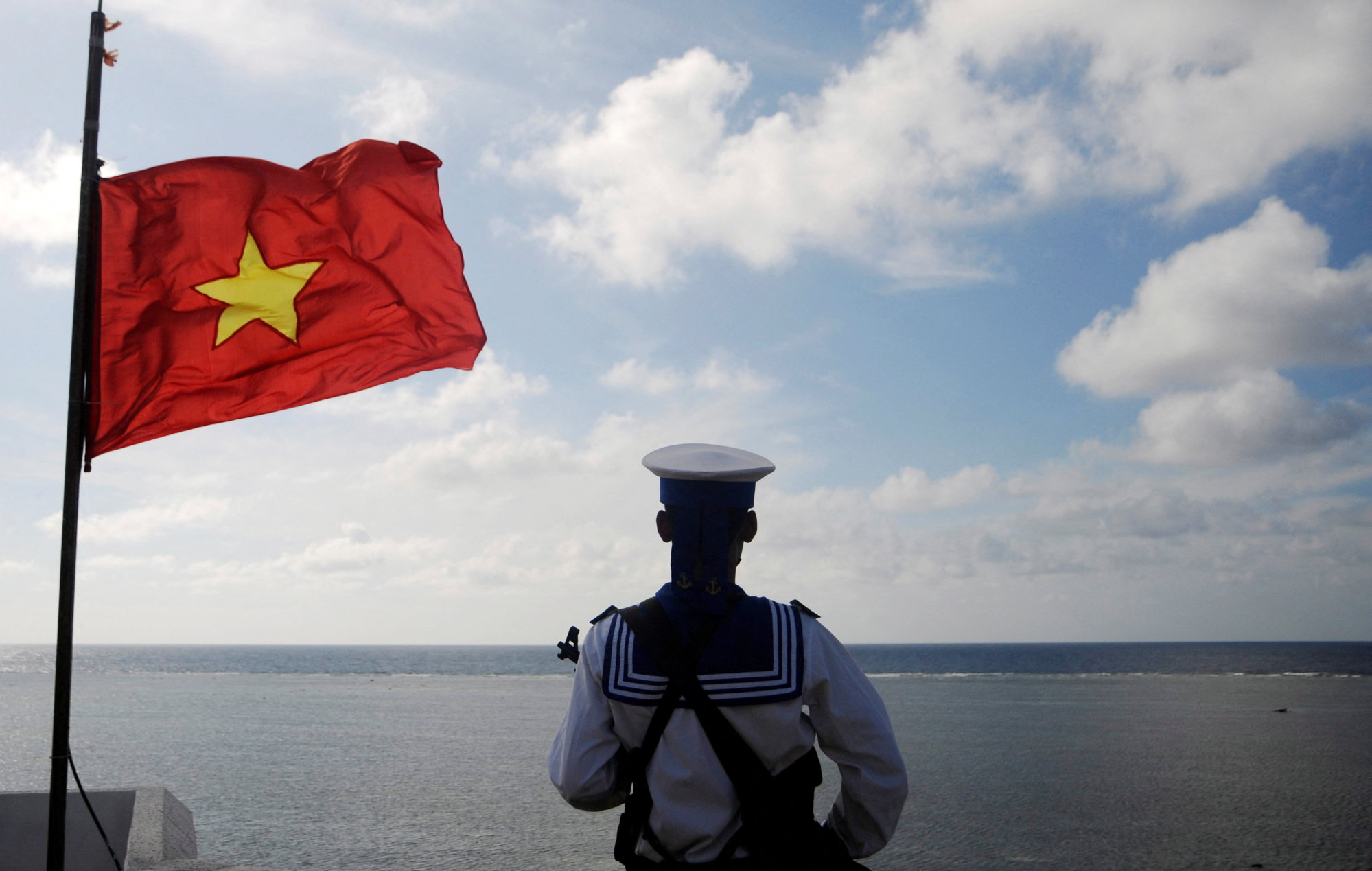

In the case of Vietnam, Huynh Tam Sang, an international-relations lecturer at Vietnam National University, said Hanoi still had to work with Beijing on illegal fishing issues and would not want to jeopardise ties.

Huynh found the idea of a “mini COC” far-fetched, but said a more flexible kind of regional “minilateralism” could address non-traditional security challenges in the disputed waterway.

“Marcos’ remarks suggest that claimant states might work together to minimise differences and explore minilateral mechanisms that suit their interests and strategic calculations,” he said.

Is Philippines’ alliance building to counter China a ‘major naval war’ risk?

Is Philippines’ alliance building to counter China a ‘major naval war’ risk?

Noting that Vietnam and the Philippines had in recent years sought defence policy dialogues and maritime collaboration, Huynh said that Vietnam and Malaysia were equally eager to strengthen maritime cooperation.

Thomas Daniel, a senior fellow specialising in foreign policy and security studies at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies in Malaysia, was also dismissive of the idea of a pact excluding China, asking: “What would a ‘mini COC’ without China accomplish, when it is China that is the recent primary source of aggression and militarisation in the South China Sea?”

He told reporters the islands are armed with weaponry that threaten other countries in the region, such as anti-ship and anti-aircraft missile systems, laser and jamming equipment and fighter jets.

[ad_2]

Source link