Thailand wants to build a brand new shipping route. Why isn’t China buying?

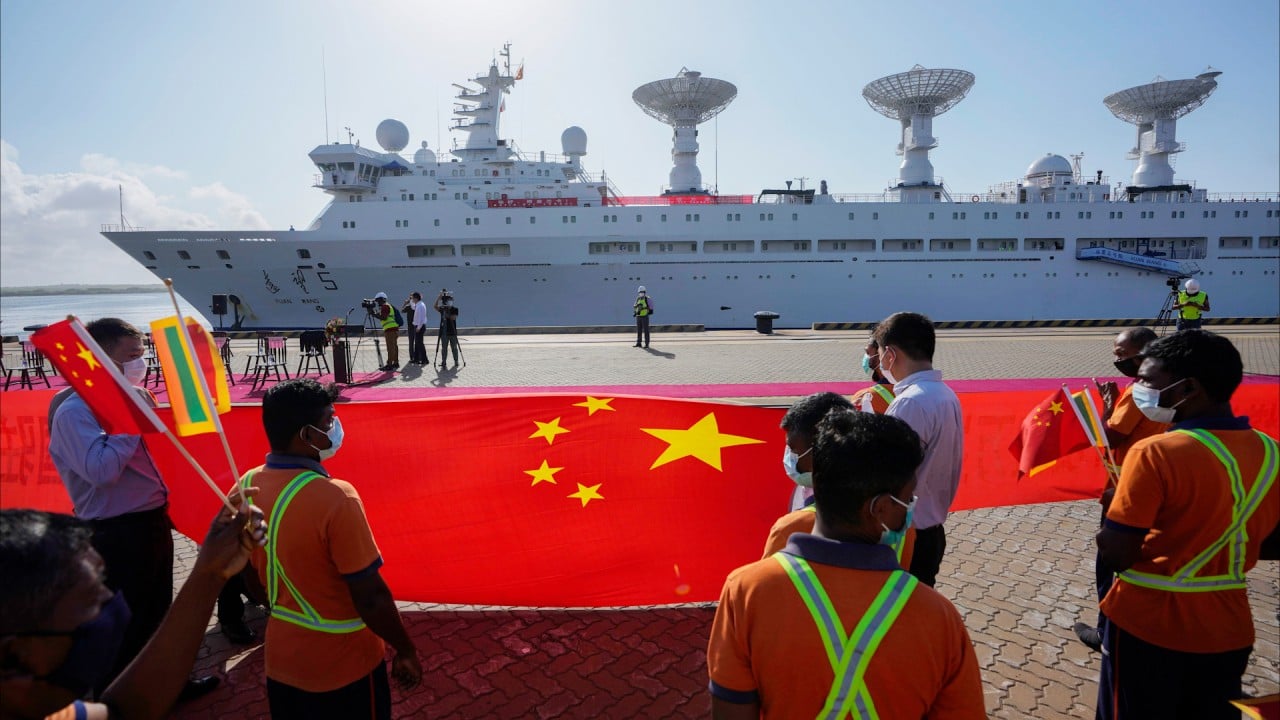

China has long been viewed as a potential patron and user, since a vast majority of its crude oil is presently sourced from the Middle East.

However, analysts have observed low Chinese interest in the Thai plan, at least for the moment.

“China is not convinced [of what] it can expect from the project,” said Lu Xiang, a senior researcher with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a Beijing-based governmental think tank.

He explained Beijing’s prudence by adding the land bridge is not the kind of high-profile, strategic project that China would throw its weight behind.

“It doesn’t look like an alternative route,” he said, adding offloading and reloading would be complex and may not cut costs to a significant degree.

Without a viable substitute, the strait is likely to remain an essential route for bringing crude from the Middle East to East Asia and consumer goods back from China.

Lu said Chinese companies may make their own assessments and explore options with their Thai partners.

“For now China may remain ambivalent, but it won’t mind the Thais engaging some commercial entities in China,” he added.

Zhu Feng, dean of the Institute of International Relations at Nanjing University, said the future of the project depends on the resolve of the Thai authorities and how political dynamics shift.

“China is unlikely to fund the project, but Chinese companies are likely to be major contractors if the project gets going,” he said.

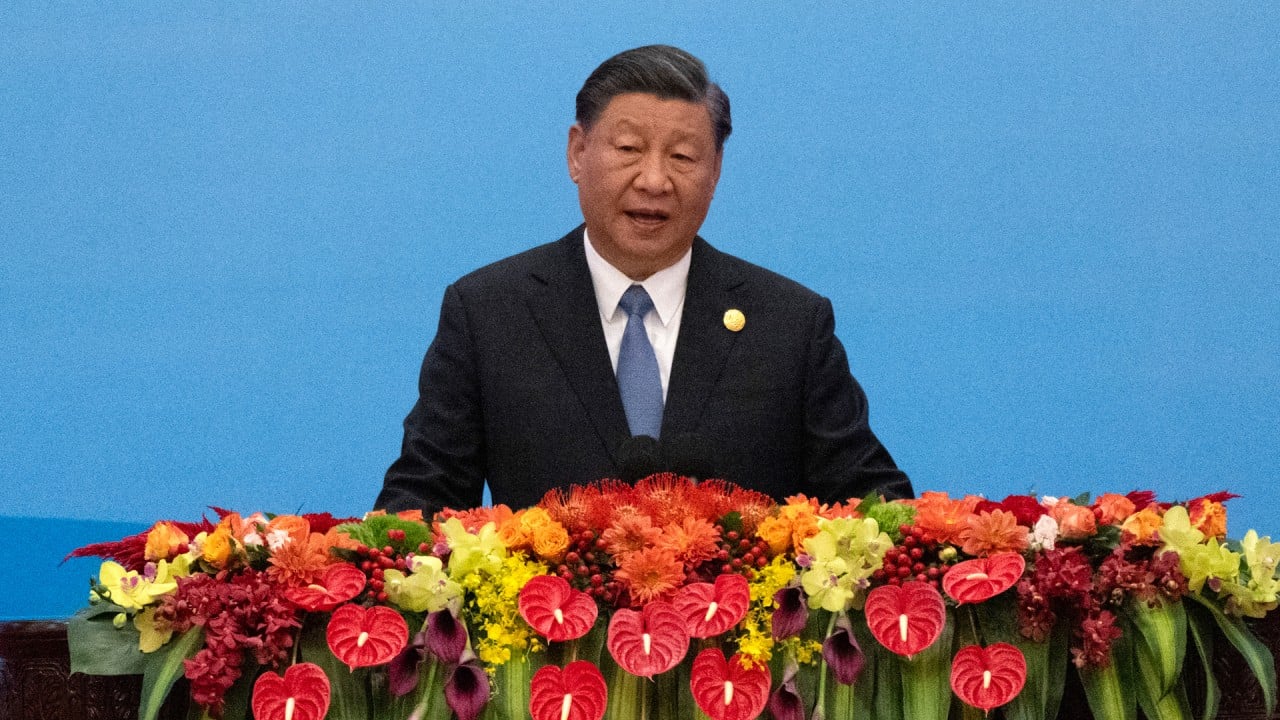

Zhu added the belt and road will be centred around rational business decisions based on investment returns for the next 10 years, and there would be fewer state-led investments to build mega projects overseas.

The project, which would link ports in the provinces of Chumpon and Ranong, is estimated to cost 1 trillion baht (US$27.7 billion) and involve a 90km (55-mile) railway and road bridge on both sides of the Gulf of Thailand and the Indian Ocean.

It could create 280,000 local jobs, Thai media reported, and Bangkok hopes to break ground in 2025 for a projected annual carrying capacity of 10 million containers after completion.

The Thai government is planning to roll out roadshows for promotional and fundraising purposes in the coming months, transport minister Suriya Juangroongruangkit was quoted as saying.

At present, it is unclear whether it will adopt a public-private partnership or build-operate-transfer model.

‘Huge potential’: China looks to belt and road to feed demand for minerals

‘Huge potential’: China looks to belt and road to feed demand for minerals

The bidding process for the contract is expected to start between April and June of next year, according to the Hong Kong Trade and Development Council, while the first phase of operational construction is projected to begin in 2030.

Southeast Asia, with its lower manufacturing costs and potential customer base of over 600 million, is a battleground for attention and investment as China’s rivalry with the United States heats up.

“Asean is more like a manufacturing hinterland of China,” said Louise Chan, deputy director of Hong Kong Trade and Development Council Research.

Chan estimated that connecting the southern part of Thailand through land bridges will save four to five days’ travel time.

However, environmental assessments and damage to the existing agriculture business could be obstacles to construction.

“Money is still a problem”, he added. “Venture capital is quite cautious with the current economic situation.”

Thailand is a major member of the belt and road. But progress on projects like high-speed rail has been slow.

Beijing has not publicly commented on the canal or the land bridge, and neither were included on the list of belt and road projects released by the National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s top economic planner.

The Kra Canal, an earlier option floated as a possible bypass of the Malacca Strait, has not garnered much attention. In 2015, the official Xinhua news agency brought up the project only to discuss its difficulty, and mentions in Chinese media have been practically nonexistent since.

If either the rail links or canal became viable, it would be a tremendous change. It would not only cut shipping costs and travel time, but also completely reshape Southeast Asia’s economic and trade landscape.

But a project’s potential is quite different from the more complicated reality. “In terms of decreasing the amount of oil going through Malacca, offloading, transporting by train and then onloading would be expensive,” said David Zweig, an emeritus professor of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Game changer or white elephant? China eyes Asean links with shipping canal

Game changer or white elephant? China eyes Asean links with shipping canal

“China is already quite busy on the Kunming-Kuala Lumpur railway (completed to Vientiane),” he added, “so they may not want to take on another project”.

Those considerations aside, interest in reducing dependency on the strait remains apparent.

The world’s second-largest economy built a 2,380km gas pipeline in 2013 with an annual transport capacity of 12 billion cubic metres, and a separate crude oil pipeline via Myanmar to bypass Malacca with an annual transport capacity of 22 million tonnes.

Rail links are also being extended to countries in Southeast Asia.

Tjia Yin-nor, an associate professor of public affairs with City University of Hong Kong, said Beijing will probably not be eager to get involved in big-ticket projects any time soon, as they have announced a turn to “small yet smart” endeavours.

The pivot marked a major shift in the country’s long-term focus.

“Initiative-related international development cooperation has been declining since 2019 both in terms of number of projects and the amount of funding,” she said.

“They will be more cautious in identifying quality projects for investment.”