Painting by Korean modern artist Park Seo-bo apparently auctioned in Hong Kong for knockdown price, drawing anger

[ad_1]

When Hong Kong company Le Comptoir closed its two-Michelin-star restaurant Écriture abruptly in September, it left staff out of a job, a landlord and suppliers owed millions in unpaid rent and bills, a kitchen full of rotting meat and vegetables – and one painting.

The painting – believed to be a three metre wide, very valuable monochrome work from the “Écriture” series by Korean artist Park Seo-bo, done on Korean hanji paper with faint straight lines running from top to bottom on a red background – was seized by order of the Hong Kong District Court.

On October 13 it was auctioned to offset some of the rent – the court estimates HK$3 million (US$384,000) – Le Comptoir owes the landlord of the space on the 26th floor of H Queen’s in Central district that housed Écriture. (The restaurant took its name from the series of Park paintings of which the one on display was one.)

In the eyes of a bailiff, one distrained item is the same as another. Even though another painting by Park had sold for HK$20.4 million at a Sotheby’s auction in Hong Kong just eight days earlier, the one in the restaurant was bundled together with a meat grinder, grease extractors, water heaters, crockery, furniture, and everything else that could be sold, and presented as a single lot with a starting price of HK$8,000.

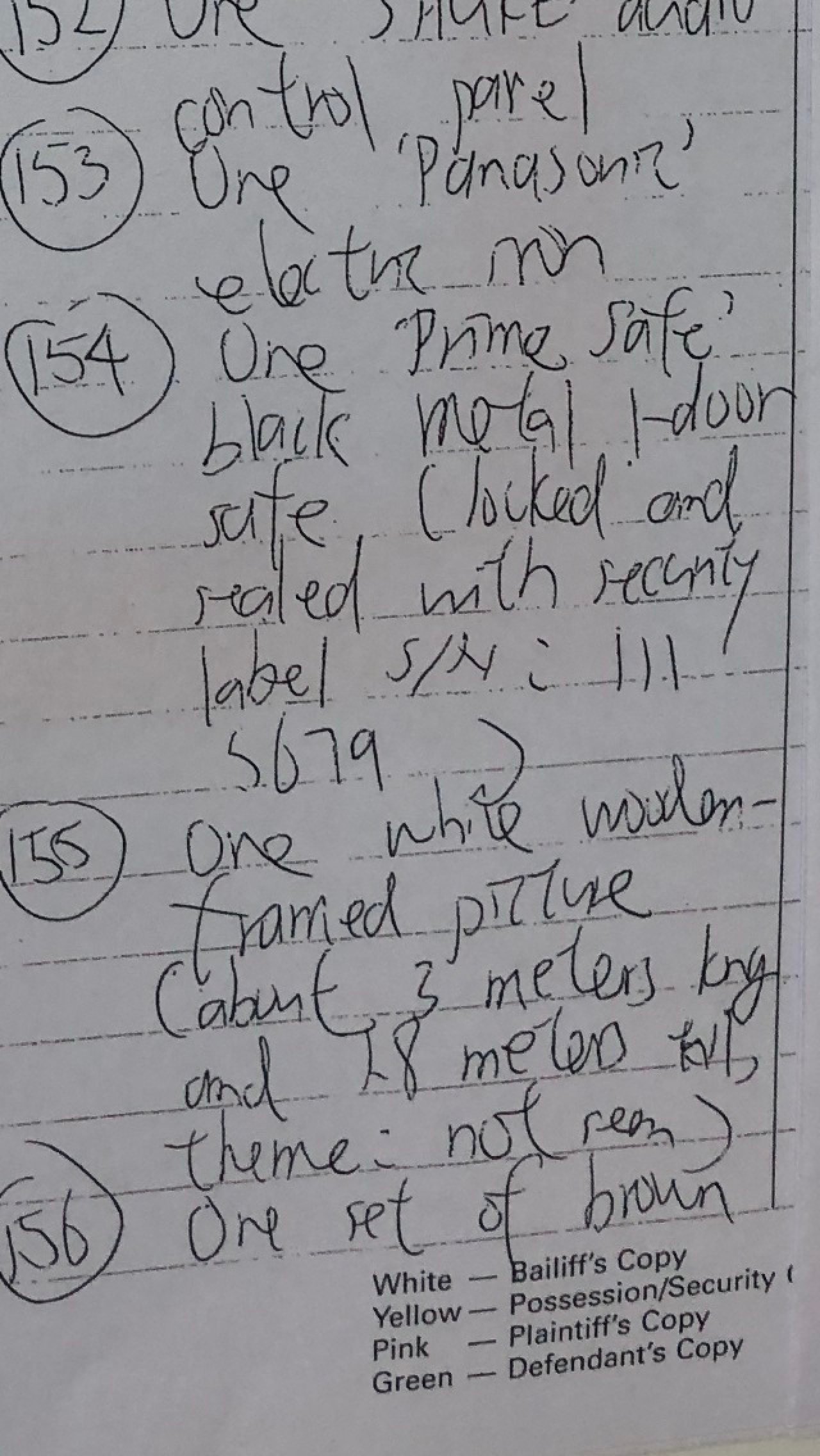

The handwritten inventory on view at Associated Surveyors & Auctioneers’ modest sale room on the 10th floor of an industrial building listed 178 items with the barest of descriptions, partly because the bailiff’s office was not able to inspect them properly.

On September 27, Judge Harold Leong decided that notices stuck to most of the items, including the painting, declaring them to be on loan from a company called Bunch of Art – part-owned by Frenchman Vivien Roussie, who runs Le Comptoir with Raphael Geismar – did not mean it had a right to the items.

He ruled in favour of the landlord and ordered the auction to go ahead. When it began, Roussie was there bidding.

Item 155 of the sale inventory was described as “one white wooden-framed picture (about 3 metres long and 1.8 metres tall, theme: not seen)”. To the uninitiated there were items that would have appeared more valuable, such as hundreds of bottles of French wine including Dom Perignon champagne and Chateau Haut-Brion reds.

The auction, barely publicised and conducted in an industrial building in Hung Hom, Kowloon, would have been considered an unorthodox way of pricing a painting by one of the leaders of South Korea’s post-war dansaekhwa movement regardless of when it was held.

“Park Seo-bo is a crucial figure not only in Korean art history but also in Korean modern and contemporary history as a whole. I believe the Hong Kong government and the restaurant owner could have taken better measures to preserve the dignity of the artist and his artwork,” said Kate Park.

She once worked for Over the Influence Gallery, founded in 2015 in Hong Kong by Geismar and which quickly expanded to Los Angeles, Bangkok and Paris.

How are we sure that item 155 was a Park Seo-bo painting?

We were unable to pull back the wrapping, but judging by its size and the red seen through a tiny gap, it resembled the painting in photographs taken in the VIP room when the restaurant was in operation.

Also, at one moment during the auction, Roussie said everyone else who showed up was “not stupid”.

“They all know that the most valuable piece is lot [sic] 155,” he said.

The way the auction was held meant that even the most ardent collectors of Park Seo-bo paintings might have had second thoughts about bidding. One collector who estimated the painting could be worth at least HK$3 million if it was a Park Seo-bo pointed out there was no guarantee of its condition, no record of its provenance, and a risk of future legal wrangling.

Still, a local Chinese man who sat in the front row of plastic chairs, accompanied by another man, joined the bidding.

After the auctioneer, who wore a T-shirt and sneakers, began the sale at 11am, the price of the unified lot rose quickly from HK$8,000. Every lifting of a finger by Roussie was matched swiftly by the mystery man – who claimed, when asked by the Post, that he knew nothing about the painting.

When the bidding reached HK$1.72 million, the auctioneer halted proceedings because he was only authorised to handle a sale up to that amount.

He phoned the bailiff’s office for instructions and restarted the auction after taking out items 157-178, which included 200 bottles of wine, in the hope the bids would come down. Yet bidding quickly reached the same figure again.

The auction had been going for about an hour by then. The auctioneer cut the list from the bottom again, removing item 156.

Perhaps someone began to worry that, if bidding reached the limit again, the auctioneer would take out item 155. The Chinese man shook his head after Roussie lodged a final bid of HK$1.52 million.

The drama wasn’t over then. There was trouble with bank transfers, and the auctioneer called everyone (including half a dozen spectators and this writer) back into the room and warned that unless the money was received over the weekend, a new auction would be called for Monday morning.

On Monday morning, a member of staff at the auctioneer’s office told the Post simply that the “transaction was completed”.

Will the painting resurface soon in an auction room that befits its status? It’s anyone’s guess.

[ad_2]

Source link