Japan gets new handbook to save celebrities from Chinese online ‘cancel culture’

Is cancel culture being cancelled? Just look at The Flash with Ezra Miller

Is cancel culture being cancelled? Just look at The Flash with Ezra Miller

“It’s understandable that the entertainment companies make such recommendations based on their commercial logic,” she said. “They certainly want to minimise the political risk and the business-related risk, while maximising the commercial value of celebrities.”

However, scholars also noted that the “patriotic and nationalistic” fans wanting to help safeguard the national interest were capable of humbling celebrities and brands when they posted things that insulted China.

Another star to suffer the ire of nationalistic Chinese fans was Chou Tzu-yu, the Taiwanese member of Korean girl group Twice. She was attacked over a television appearance where she was seen waving the flag of Taiwan.

Chinese fans have changed over recent years from passive pop culture consumers to an influential force able to both grow their idols’ influence – or shred it.

A slogan first used in 2016 after Seoul announced the installation of a US-made Terminal High Altitude Area Defence system – “Adoring the idol should be inferior to safeguarding the interests of the country” – has now become the leading principle among fans when dealing with disrespectful comments by celebrities.

The growth of fan activism in China is something that has come about gradually, shaped by certain events, according to Zhuang Yuyi, an associate professor at the Xiamen University’s political science department.

Zhuang said the manual would greatly help both artists and companies.

“The manual has made clear some of the unwritten and unofficial rules that every artist would follow when entering the China market,” he said.

“When performing overseas, it is necessary to respect the different history, customs and traditions of each country and avoid direct involvement in sensitive political or discriminatory issues.”

Zhuang also said the inclusion in the manual of dates when stars and companies should avoid making important announcements would help equip them with the cultural sensitivity they needed to survive.

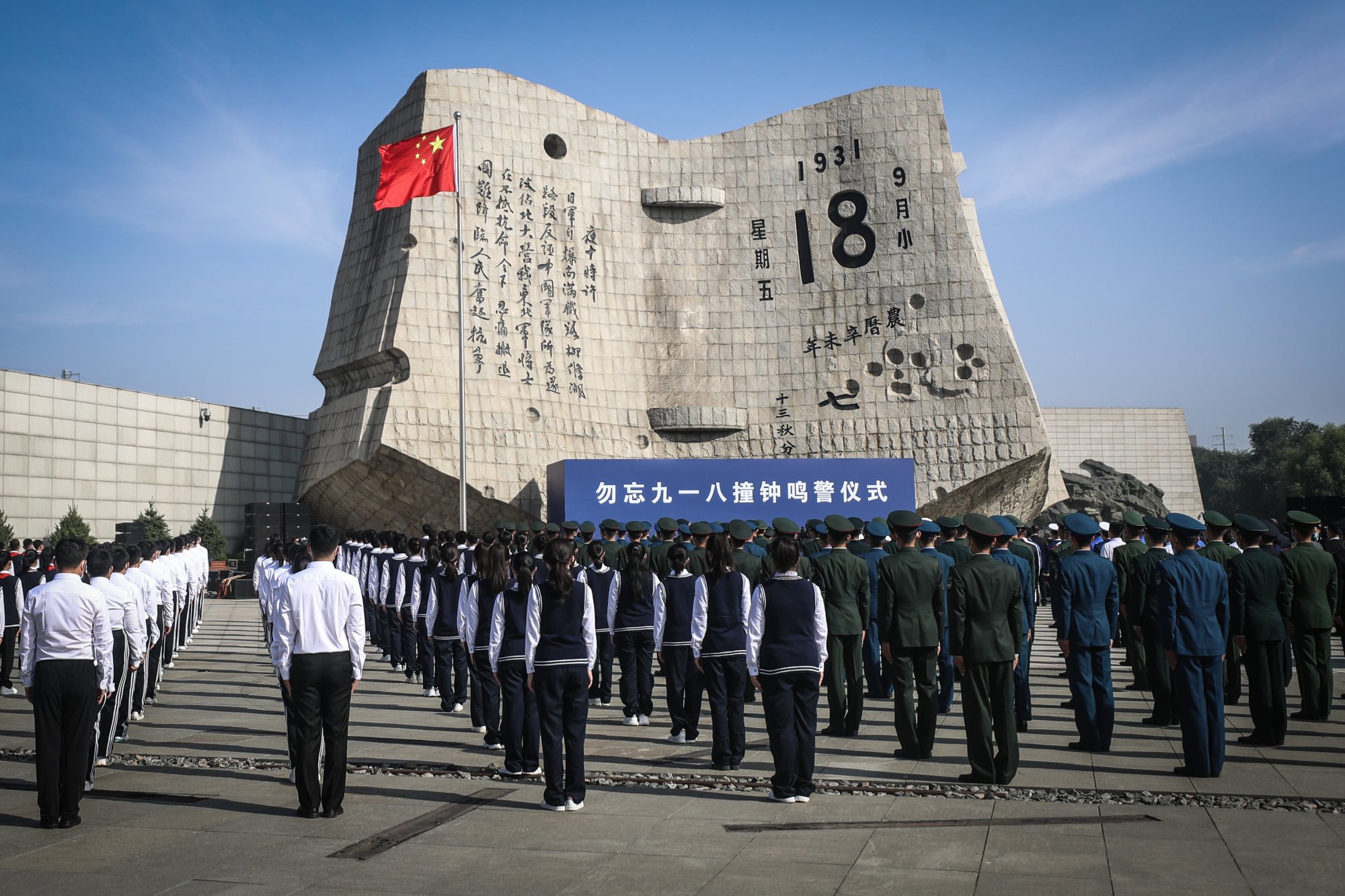

The manual lists 18 such dates which are occasions of China’s “national humiliation”. It includes September 18, the anniversary of the 1931 Mukden incident marking the beginning of Japan’s invasion of China, as well as July 7, the date in 1937 when the Marco Polo Bridge incident led to the start of the second Sino-Japanese war.

It is not just foreign stars and brands that are caught up in online friction; domestic celebrities have also suffered the anger of Chinese fans when they have been caught making insensitive social media posts.

Chinese actor Zhang Zhehan had deals with more than 20 brands terminated and faced a domestic boycott in 2021 over three-year-old pictures of him posing at the Yasukuni Shrine.

Wang noted that having such political messages being part of the social domain would be beneficial to the Chinese government, with it potentially not needing to send out its own similar messages as frequently.

However, another researcher, who asked not to be named, said the manual should be taken with a pinch of salt, explaining that the market might eventually become a “minefield” with no one able to predict what the next contentious issue will be.

Wang agreed that the list of rules could continue to expand as people worried over potentially hurting others’ feelings.

“Issues like the ones mentioned in the manual are becoming a gold standard deciding whether you are a friend or a foe,” she said.

Xiamen University’s Zhang said with the growing entanglement of politics, entertainment and even sports, the manual helped set a boundary to avoid igniting unexpected tensions.

“If it can help moderate prickly relations, that is a good thing. If it doesn’t, then at least it won’t add fuel to the fire.”