Opinion: Why Rupert Murdoch stepping down can only be good news

There are few journalists alive today, and few major news organisations, that have not had their lives and careers shaped in some way by Rupert Murdoch, for good or bad. For consumers of news, he has done more than any other media mogul to determine what we read about, and the narrative around which it is spun.

I, for one, have had my journalistic career impacted by Murdoch, though not in a bad way. And to get my prejudices clearly out on the table, I regard most of Murdoch’s influences on the business in general as harmful.

Rupert Murdoch’s love affair with the media undoubtedly started in childhood, watching his father Keith run several newspapers and radio stations in Australia. He studied politics, philosophy and economics at Worcester College Oxford, and worked for a time at the Daily Express in the UK. After his father died in 1952, he returned to Australia to take over his father’s reins.

He went on to launch The Australian, the country’s first national broadsheet, became a dominant force in the UK media, then turned his sights on the US, consuming the New York Post, The Wall Street Journal, and then Fox News. Politically agnostic, always heavily hands-on, he stuck to the mantra of melding entertainment with news, and leveraged his media influence to exert real political power.

As an earnest, Methodist-raised working class kid, I was appalled, and much preferred the Daily Mirror. I saw the value of tabloid newspapers in a democracy: my father worked in a factory, and could only read his newspaper in his morning toilet break. Broadsheet newspapers were too large and too long-winded to be readable sitting on the toilet.

For me, Murdoch’s Sun was the anti-Christ. It infuriated me that it was so successful, and it was a key reason I trained as a journalist with the Mirror, where the honourable mission was to equip “plain working-class folk” with all the honest, balanced information they needed to participate effectively in a democracy.

Sadly, so seductive was Murdoch’s “sex and scandal” formula that by the time I finished journalism training, the Mirror was sliding haplessly in the same direction. Needless to say, I joined not the Mirror, but the Financial Times – a great disappointment to my father, who saw the FT as wordy and unreadable, and as distant from my tabloid mission as it was possible to get.

It was shortly after this that Murdoch engineered a master stroke that was to transform British journalism, bringing it into the 20th century. This cemented Murdoch’s reputation as a cunning and ruthless entrepreneur.

After he bought The Times and The Sunday Times in 1981 (two years after they had been enfeebled by a year-long closure triggered by the former owners’ unsuccessful efforts to modernise printing processes and reform antiquated print union practices), he stealthily set about a second attack on Fleet Street’s Victorian print unions by moving his print operations to a new hi-tech facility in Wapping, East London.

This time, the formidable print unions were outsmarted and their monopoly grip on the newspaper business was broken. Within just a few years, journalism was computerised, colour was introduced and the “hot metal” print unions were history.

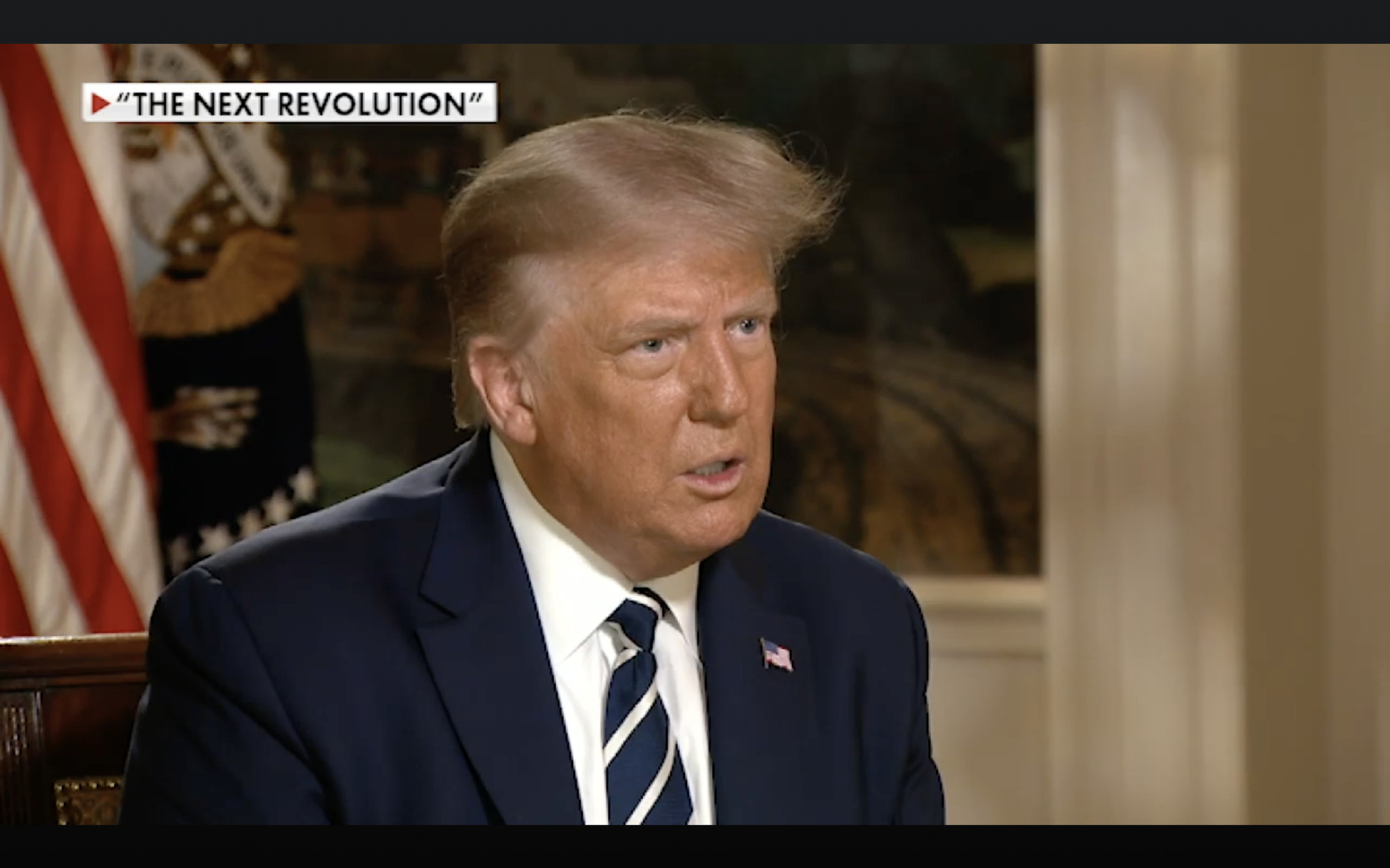

Murdoch’s fascination for Hong Kong quickly subsided, however, in part because of the increasingly tricky politics as we headed towards 1997, and in part because of his decision to sink his teeth into the US media industry. His role at the heart of Fox News, aligning with Donald Trump and roiling US populist politics, will perhaps be his greatest – and most regrettable – legacy.

His impact in Hong Kong (and China) never matched his impact in the US and the UK, and he sold the SCMP to Robert Kuok’s Kerry Media in 1993.

Murdoch’s son Lachlan faces daunting challenges – not least keeping his father off his back. The News Corp empire spans an old media world that has negligible hold on new, internet-based media, and it will be Lachlan’s challenge to forge such a transition. I suspect the Murdoch star has waned and, on balance, I think that will be a good thing.

David Dodwell is CEO of the trade policy and international relations consultancy Strategic Access, focused on developments and challenges facing the Asia-Pacific over the past four decades