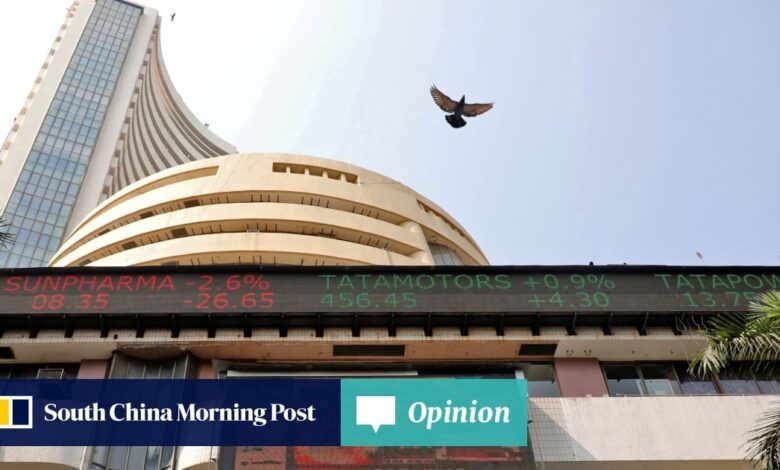

Opinion: Global investors’ love affair with India is about to be tested

“If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” This statement by Herbert Stein, a former chairman of the US Council of Economic Advisers, referred to America’s rising public debt. However, it is equally applicable, if not more so, to surging asset prices.

This is questionable. What is clear is that India is ticking many of the boxes that matter to international investors. Not only is it the world’s fastest-growing major economy – it expanded at an annualised rate of 7.8 per cent in the second quarter, powered by the service sector – it boasts strong corporate earnings driven by a long-awaited pickup in private investment.

Just as importantly, Asia’s third-largest economy is the leading beneficiary of the sharp deterioration in sentiment towards China over the past several years. Although Indian stocks were already surging before Chinese shares peaked in early 2021, the rally has been turbocharged by the succession of policy shocks in China.

Yet, the more interest there is in India on the part of global investors, the greater the scrutiny of its economy and markets. Last week, JPMorgan announced that it will add India to its widely followed index of emerging market local currency bonds, setting the stage for billions of dollars of foreign inflows that will help the government finance its fiscal and current account deficits.

While India’s inclusion in the index will be phased over a period of 10 months, starting in June 2024, its weighting is expected to eventually reach the maximum allowed – 10 per cent – on a par with China’s current weight. JPMorgan anticipates US$15 billion to US$20 billion of inflows over a 10-month period, which would be almost as much as the current level of overseas holdings of Indian domestic bonds.

Troubled China-India relationship means Asian century remains elusive

Troubled China-India relationship means Asian century remains elusive

This is good news for foreign investors seeking more exposure to one of Asia’s largest sovereign debt markets. It is also a victory for Indian technocrats who have been pushing for index inclusion for years. On the other hand, it will test both India’s willingness to open up to more foreign capital at a time when markets are vulnerable, and investors’ tolerance of macroeconomic risks in India.

Unlike in some other emerging markets, notably Malaysia and South Africa, foreign ownership of local government bonds in India is very low, currently standing at just 2 per cent of outstanding debt.

Indian politicians have long been wary of “hot money” flows that could destabilise the economy. They have also been reluctant to cede more control over policy to so-called “bond vigilantes” who force profligate governments to impose austerity by driving up their borrowing costs sharply.

Index inclusion will subject India’s economy and markets to greater scrutiny and stricter governance standards. With a fiscal deficit of nearly 9 per cent of GDP – the biggest among the members of JPMorgan’s emerging market bond index – and a much higher public debt burden than in other countries with the same credit rating, India’s relationship with global debt investors is likely to become more tense.

Yet, this is part and parcel of playing a bigger role in the global economy and markets. The question is whether index inclusion will encourage India to come up with a more credible fiscal consolidation plan.

On Wednesday, Fitch Ratings noted that there are examples of countries that joined global bond and equity indices and ended up pursuing “policies that had clear adverse effects on foreign investor confidence”. China is a prime example.

Fortunately for India, its appeal in the eyes of global investors partly stems from its position as a compelling alternative to China. However, both countries remain suspicious of foreign capital. The difference is that India has sentiment firmly on its side, for now at least.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory