Middle East’s Mandarin push sets the tone for ‘convergence’ with China on trade

[ad_1]

Since then, more than 150 of the UAE’s state-run secondary schools – with over 50,000 students – have introduced Mandarin classes and the aim is to reach 200 schools by 2030.

The UAE is home to more than 300,000 Chinese nationals, the biggest diaspora in the region, and it is Beijing’s second-biggest trading partner in the Middle East.

Many analysts tend to focus on belt and road infrastructure investments and overlook the initiative’s cultural and human development aspects, but “Arabs learning Chinese and vice versa is a central enabler of both sides’ long-term convergence of interests and visions”, Aboudouh said.

Egypt launched a pilot project in Ocober last year to introduce Mandarin as an optional subject at a dozen state-run middle schools.

Hong Kong must do its homework to profit from warmer-than-ever China-Saudi ties

Hong Kong must do its homework to profit from warmer-than-ever China-Saudi ties

Mandarin language classes are not “a novelty in the region because Confucius Institutes were established in the Middle East during the 2000s, starting with Beirut in 2006”, Chay said.

Confucius Institutes are used by Beijing to promote cultural outreach and Mandarin language teaching. The first of these institutes to open in a Gulf Arab monarchy was established in Abu Dhabi in 2010.

In June, the number of Confucius Institutes in the Middle East and North Africa rose to 23 across 13 countries with the opening of the first branch in Saudi Arabia at Prince Sultan University in Riyadh.

Chinese language learning and China studies departments have also been established at universities in 14 countries across the Arab world.

Still a challenge

Despite the political push for more concrete steps to enhance Mandarin language programmes in the Gulf, the process is hampered by challenges such as “deficiencies in the Saudi and Emirati public education systems – a chronic pan-Arab problem – and their inability to build students’ foreign language skills effectively”, Aboudouh said.

Saudi authorities prepare their teachers to teach Mandarin with a one-year course taught by Saudi instructors who primarily promote rote learning.

“Political will is not matched by financial generosity, as it is more expensive to bring native Chinese instructors to the Gulf than to train local teachers,” he said.

Such shortcomings make Mandarin – already a difficult language to learn – less appealing to students.

It will also “take time for Arab students” to find Mandarin as attractive an option as Western languages, such as English or French, “due to historical perceptions and psychological barriers and also seeing it as a powerful skill to have in the labour market”, Aboudouh said.

Some thought the Chinese language would die. They were wrong

Some thought the Chinese language would die. They were wrong

Despite the growth of China’s commercial presence in the Gulf, Mandarin is not yet widely used in business circles there.

In the UAE, some businesses with operations in China are sending employees to Confucius Institutes to learn Mandarin.

But this is “limited since English seems to be the primary language of exchange between Arabs and Chinese so far”, said Mohammed Abdul Rahman Baharoon, director general of the Dubai Public Research Centre, an independent UAE think tank.

More than 6,000 Chinese-owned companies operate in the UAE, the major business and logistical hub of the Middle East.

While it is “natural” for Gulf Arab countries to want more cultural exchanges with China “considering the exposure to Chinese business and community”, interest in Mandarin is “not as big” as other languages spoken by large expatriate communities, Baharoon said.

Hindi and Urdu, the closely related national languages of India and Pakistan respectively, are “possibly the third-most widely spoken language in the UAE”, he said.

Arabic in China

But the number of Chinese nationals learning Arabic is growing fast because it has become a compulsory part of the curriculum in many state schools in China, and is now taught at 37 universities and institutes across the country.

“There are definitely more Chinese speaking Arabic than Arabs speaking Chinese, mainly because of the number of Muslim-Chinese,” Baharoon said.

Considering the growing interest of China and Gulf Arab states in increasing cultural understanding, “it’s not unusual to see a spike in interest in the Arabic language among Chinese who are opening businesses in the region”, he said.

The rising economic and political status of Gulf countries “puts Arabic in high demand as an attractive option” for Chinese nationals seeking to learn a foreign language, Aboudouh said.

Arabic is “very useful if you are engaged in finance, commercial activities, investments abroad or even interested in diversifying your options”, he said.

China looks to shore up belt-and-road deals with Middle East cash, partnerships

China looks to shore up belt-and-road deals with Middle East cash, partnerships

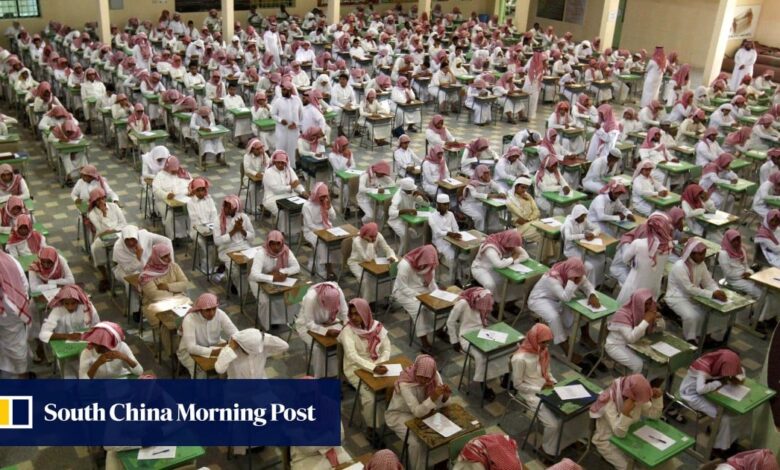

Similar motivations have driven the Saudi government’s decision to make Mandarin an integral part of its secondary school curriculum.

The kingdom’s decision reflects its policy of seeking to “benefit from the languages of technologically advanced countries”, said Najah al-Otaibi, a Saudi political analyst based in London.

Previously, Saudi Arabia’s schools and universities focused on teaching English and European languages to improve the job prospects of students.

“However, we are now seeing a desire among the leadership in Saudi Arabia to prepare a new generation of Saudis to become fluent in the Chinese language, due to China’s increasing economic and political role,” al-Otaibi said.

It is also “an opportunity for Saudi companies and individuals to better access the Chinese market and benefit from Chinese expertise and knowledge”, she said.

[ad_2]

Source link